|

|

Covert/Larch Historic District

Overview | Historical Perspective | Documentary Research

Archaeology | Archaeology Update (January 2008)

Overview

In a small neighborhood shadowed by the Pulaski Skyway, investigators trained in architectural history identified a group of houses that had been

built in the 1860s and 70s. Many of them still had architectural features from that time, though all had been updated over the years.

Formed by |

| Covert Street and Larch Avenue on the north side of St. Paul’s Avenue, the tiny, triangular enclave is cut off from other residential

neighborhoods by industries, railroad tracks, and some of the most heavily trafficked roadways in the United States. But it invokes a sense of

the past, and research into property and census records has revealed that the neighborhood’s |

|

history perfectly reflects the development of Jersey City’s early working class neighborhoods. Archaeologists also

explored the properties by digging test trenches, and discovered that many of the backyards contain deposits of household items discarded by

19th-century residents.

Background on the history of the area, specific historic occupation sequences for each lot, descriptions and photographs of the standing structures,

and the preliminary archaeological investigation were used to evaluate the district. The findings of the initial investigation were reported to

the State Historic

Preservation Office in 1998, and the Covert/Larch Historic District was created. It is considered to be eligible for listing on the National

Register of Historic Places, and according to federal law, efforts must be made to preserve it. But given the density of development in the area,

there is little room for changing the course of the highway – unavoidably, the houses and yards will be destroyed when a new ramp is built. In order

to partially mitigate (lessen) this damage to Jersey City’s historic resources, it was agreed that the houses will be recorded with photographs and

the archaeological deposits will be fully excavated so that information about the early residents can be obtained through study of their discarded

household items. Excavations began in 2005.

Historical Perspective

While it is entirely possible that prehistoric inhabitants of this part of New Jersey visited the project area, little evidence of their presence

has been found here. Impermanent occupation sites do not leave substantial traces, and the dense development of the area in recent times is likely

to have obliterated them.

European settlement in the project vicinity began with the establishment of the village of Bergen in 1660. This planned settlement had a rectilinear

plan with a central public square that is still reflected in the present day street pattern of Jersey City (Bergen Square is intersected by Bergen

Avenue and Academy Street and surrounded by Newkirk, Van Reypen, and Vroom Streets and Tuers Avenue). The surrounding lands were subdivided and

assigned to Bergen’s Dutch settlers for farmlands, meadow, and woodlots. These landholdings took the form of long, narrow “long lots” that included

upland areas for cultivation, meadow to be used for pasturage, and access to the Hackensack River and the Middle Road (now Tonnele Avenue). The

Newark Turnpike Company was incorporated in 1804 to build a toll road from Paulus Hook in Jersey City to a new bridge over the Hackensack. The

roadway created by this turnpike company remains in use today -- Newark Avenue. But the area that includes Covert/Larch remained undeveloped well

into the 1800s.

A map of the Jersey City area published in 1841 shows how rural the Covert/Larch vicinity remained at that time. The Middle Road (Tonnele Avenue),

“Old Ferry Road” (now Van Winkle Avenue), and the Newark Turnpike (Newark Avenue) were all depicted, as were the Paterson and Hudson River Railroad

(running to the west of and parallel to the Middle Road) and New Jersey Railroad (running adjacent to the turnpike). There were only a few

structures, including dwellings and railroad buildings, scattered along the roads.

|

Click to view larger image

|

Click to view larger image

|

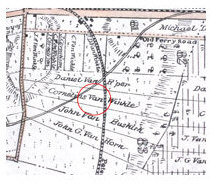

This map was originally drawn in 1841, and was reproduced in 1880. The arrow points to the location

of the Covert/Larch Historic District. John Van Buskirk and Cornelius Van Winkle were the owners of “long lots” that encompassed the district, to

the north of the Newark Turnpike (now Newark Avenue) which extended from the Middle Road (later Tonnele Avenue) to the Hackensack River. Both men

had inherited these lands from their father-in-law Garret Van Riper. The Van Riper family had held this property since the 18th century.

(See Winfield, Charles H. 1872. History of the Land Titles in Hudson County.

Wynkoop & Hallenbeck, New York.)

|

| The Town of Hudson, which would be absorbed by Jersey City in 1870, was established in 1852. It was centered at the Five Corners (North Bergen),

but soon grew outward. The town encompassed the Cover-Larch area when real estate interests dominated by German Americans from New York City

organized as the Town of Hudson Land Association and obtained a large tract of land. This new development tract was laid out in 1854 along a new

street named German Avenue (now St. Paul’s Avenue), from Tonnele Avenue west beyond James Avenue. |

Click to view larger image

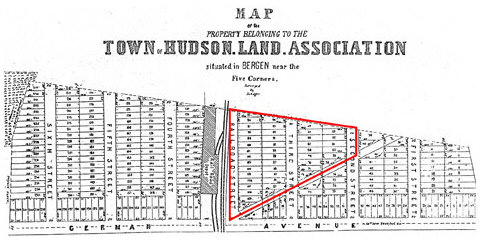

Map of the property belonging to the town of Hudson Land Association situated in Bergen near the Five Corners 1854. The

present-day Covert/Larch district is outlined.

Map of the property belonging to the town of Hudson Land Association situated in Bergen near the Five Corners 1854. The

present-day Covert/Larch district is outlined.

The former Hudson City area was slowly incorporated into Jersey City in the late 1800s, but development remained relatively sparse. The most heavily

developed section was the former Town of Hudson Land Association subdivision to the north of St. Paul’s Avenue between Tonnele and James Avenues,

known as the West End, or Marion, section of town. Most of the residents were of German and Irish descent. There were also some shops and small

industries, such as the People’s Gas Light Company Gas Works on St. Paul’s Avenue, railroad-related buildings, and a school on Tonnele Avenue.

|

Click to view larger image

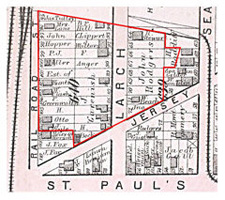

The Covert/Larch Historic District as mapped

The Covert/Larch Historic District as mapped

by Hopkins in 1873. The boundaries for

each property and its owner in that year

are indicated on the map. |

Click to view larger image

The Covert/Larch Historic District as mapped

The Covert/Larch Historic District as mapped

by Fowler 1887. The present-day

district is outlined in red. |

The full incorporation of the project area as part of urban Jersey City occurred during the first several decades of the 20th century. Development

still concentrated in and around the earlier neighborhoods. Now, immigrant families from Southern and Eastern Europe began to appear in the census

records, replacing the earlier German and Irish descended residents. A major highway corridor was developed along the right-of-way of the Jersey

City Water Works Pipeline during the 1920s and 1930s, and new industries -- the Brunswick Laundry, the P. Lorillard Company Factory, and the American

Can Company Factory -- appeared on the blocks surrounding the Covert/Larch district.

As is so often the case, the continual expansion and interconnection of arterial highways through Jersey City has been at the expense of urban

neighborhoods. Ultimately, the Covert/Larch district was almost completely cut off physically from other residential and commercial neighborhoods.

The block was traversed diagonally by the U.S. Routes 1&9 corridor, and the southern half was demolished. Seaman Avenue was de-mapped and the

remaining houses that lined it were demolished when a ramp onto the St. Paul’s Avenue Viaduct was built. |

Documentary Research

Historic documents and archaeological collections provide information about the people who once lived in the Covert/Larch Historic District. The

records that are typically used to learn about occupants of houses include property records and probate records such as wills, censuses,

and city directories.

Researchers first identified early property owners by tracing old deeds at the Hudson County Courthouse and Administration Building in Jersey City

and at the New Jersey

Division of Archives and Records Management in Trenton. If an owner died, researchers turned to other kinds of public records, namely wills and probate inventories.

Some historic maps identify property owners and provide a good snapshot of the area for a specific year. The 1873 Combined Atlas of the State of New

Jersey and the County of Hudson by Hopkins, for example, shows property owners on Railroad Street (later Covert Street), Larch Avenue,

and Seaman Avenue.

Archaeologists are interested in the homeowners, who were typically the heads of households or married couples, in other family members and in any

tenants. Tenants and housed boarders do not appear on maps or property deeds.

The New Jersey State Census, taken in the middle of each decade, and the U.S./Federal Census, conducted every 10 years are important sources for all

of the actual occupants, including children and relatives, tenants, and boarders. To determine who lived in a house during the |

years between censuses, researchers can look up the residents’ names in

city directories similar to today’s phone books that are available in the New Jersey Room at the

Jersey City Free

Public Library.

The Beck Houses and the Gavenesch/Balbo House illustrate the process of historical discovery that aided in the reconstruction of the Covert/Larch neighborhood. |

The Beck/Thorpe/Altvatter House and

The Beck/Thorpe/Altvatter House and

Tenant House Sites at 73 Larch Avenue

and 75 Larch Avenue are as they

appeared in 2006.

|

The Beck houses at 73 and 75 Larch Avenue

The 1873 Combined Atlas of the State of New Jersey and the County of Hudson by Hopkins identified the Beck Houses. The map shows one dwelling

on the triangular lot at what would later become 73 Larch Avenue and one at 75 Larch Avenue, both owned by H. Beck. Lot 82 has an unusual triangular

shape due to the diagonal right of way for the Jersey City Water Works Pipeline

(pdf 21.7m) that cuts across the block. Beck’s property was initially transferred as two parcels from the

Town of Hudson Land Association to Peter Hoersch in 1859 (Lot 82) and to Fredrick Knubel in 1860 (Lot 83). Henry Beck had

purchased Lot 82 in 1862 for $110 and Lot 83 in 1863 for $230.

|

Click to view larger image

The1873 Combined Atlas of the State of

The1873 Combined Atlas of the State of

New Jersey and the County of Hudson

shows the properties owned by H. Beck, but the exact building and owner-occupation dates are unknown. The price Beck paid for Lot 83 at 75 Larch, which was more than double what he had paid for Lot 82 at 73 Larch one year earlier, suggests that 75 Larch Avenue had a house. Later documents showed that the dwelling at 73 Larch Avenue, which stood at the extra-wide rear part of the property, was a two-family house, while 75 Larch, built on a narrow lot, was a one-family dwelling. Both houses depicted in the Atlas were still standing at the time of our research.

|

Though the 1870 Federal Census does not list the Becks on Larch Avenue, Gopsill’s Jersey City, Hudson City and Hoboken Directory for

1864-1865 lists Henry Beck in a house on “3d n St. Paul’s av.” Larch Avenue was originally known as 3rd Street.

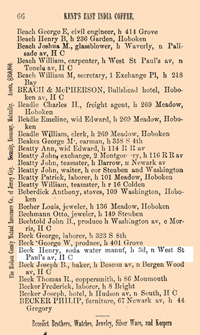

Click to view larger image

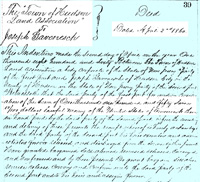

The transcribed deed dated July 6, 1863 for Town

of Hudson Land Association Lot Number 83 or 75

Larch Avenue shows the sale of the property from Friedrich and Anna Catherine Knubel to Henry Beck

for $230. The exact dimensions of this small house

lot, highlighted in white, were written into the deed.

|

Click to view larger image

A page from Gopsill’s Jersey City,

A page from Gopsill’s Jersey City,

Hudson City and Hoboken Directory

for 1864-1865 shows Henry

Beck’s residence as “3d n West

St. Paul’s av, H C.”

|

The 1880 Federal Census tells us that Beck, a 57-year-old Hessian immigrant, his 46-year-old wife Christiana, who was also Hessian, his 17-year-old

son Henry and four other children occupied a house at 73 Larch Avenue. This census lists Beck as a laborer, though earlier city directories list him

as a soda water manufacturer and a shoemaker.

|

The 1880 Census also shows that the two-family dwelling at 73 Larch Avenue housed a Prussian family, the Knops: 25-year-old Fredrick, a laborer,

21-year-old Lina and their 2-month-old adopted daughter.

According to the census, the Becks leased their smaller house at 75 Larch Avenue to James Joyce, a 38-year-old laborer, and his 27-year-old wife

Sarah, both born in Ireland. The Joyces had four children, James, Mary, John and Thomas, all below 10 years of age. Mr. Joyce was listed in the

1878-1879 directory, but he |

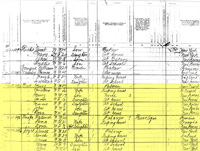

Click to view larger image

Page from the 1880 Federal Census

Page from the 1880 Federal Census

shows the Beck, Knop, and Joyce

families living at 73 and 75 Larch

Avenue (highlighted in yellow.).

|

does not appear in subsequent directories. This suggests that the Irish family only lived in the Beck’s tenant house for a short period of time.

Henry Beck died in 1886. Subsequent probate of his will stipulated that his daughters Catherine Beck Thorpe and Annie Beck Altvatter, both living at

73 Larch, and his minor son John Beck receive his property. Additional probate records indicate that Beck had $2500 in real property at the time of

his death, which was divided among the three children. Court records that were filed with his will and probate show that he left his oldest son Henry

Beck, who was in a reform house, one dollar.

|

Both of Henry Beck’s daughters married, and brought their husbands to live in their father’s house. Vital records -- certificates of births,

marriages, and deaths, often used by genealogists -- show that Annie Beck married Frank Altvatter in 1886, the year of her father’s death. Vital

records are sometimes available online through various non-profit and commercial genealogical research companies, or at municipal or county records

offices. Archaeologists are particularly interested in these records, because life-cycle events like marrying and having children, growing old and dying, are reflected in the material culture of a household. The record of

Catherine’s marriage to Harry Thorpe has not yet been found, but the city directories show that Harry, who was listed at that time as a ferryman, first came to

live with his in-laws |

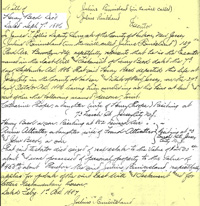

Click to view larger image

The application for probate of Henry

The application for probate of Henry

Beck’s will, dated September 7, 1886,

asserts his two daughters and one son

would receive his estate. This document

shows that his two daughters,

Catherine Thorpe and Annie

Altvatter and their husbands were

living at 73 Larch Avenue.

|

in 1885. The Thorpes and Altvatters were listed at either 73 Larch or 75 Larch in the city directories during the 1890s.

According to the 1900 Federal Census, Harry Thorpe was a 39-year-old clerk from England. Kate Beck Thorpe was also 39 years old. Frank Altvatter was

a 35-year-old German American engineer, Annie Beck Altvatter was 32 years old, and their daughter Amelia was 11 years old.

Wills, deeds, and census information fill in the early 20th Century history of 73 Larch. The Thorpes and Altvatters continued to live there together

until Catherine Thorpe died in 1917, when she left her estate, including her share of the property, to her sister Annie and brother John. The

Altvatters stayed until they sold their property to their neighbor, Angela Balbo, in 1919. |

The small house at 75 Larch was continually leased. A woman named Martha Crane and her two daughters were listed here in the 1895 New Jersey State

Census. The 1900 Federal Census shows a different tenant family, 29-year-old Charles Staub, an embroiderer from Switzerland, his 23-year-old wife

Louisa, and their daughter Bertha as residents. The Staubs do not appear in the directories in the 1900s and they,

|

Click to view larger image

A detail from a hard-to-read page of the

A detail from a hard-to-read page of the

1900 Federal Census shows, from top to bottom, the Staube, Thorpe, and Altvatter families

as residents of 73 Larch Avenue.

|

like the Knops, and the Cranes, may have been short-term

tenants. It is difficult to trace tenants yearly, because often they relocated on the traditional moving day of May 1. A name gleaned from a census

can only be followed in the directories for one or two years.

The Gavenesch/Balbo House at 77 Larch Avenue

The Gavenesch/Balbo House was lived in by tenants rather than its owners for more than twenty years. When a house has repeated short-term residences

by multiple families, the history can be difficult to trace.

Deeds show that Joseph Gavenesch purchased several lots from the Town of Hudson Land Association in 1860. Spellings are often variable in the older

records. The 1870 Federal Census shows "Gavenesh" as a 50-year-old mustard dealer who lived in this neighborhood with his

38-year-old wife, Magdalena, their 17-year-old daughter Johanna, their 15-year-old son Adolph, who worked as clerk, and six other children. Joseph

and Magdalena were from Saxony, Germany.

|

Click to view larger image

The 1870 Census verifies that Joseph

The 1870 Census verifies that Joseph

and Magdelina Gavenesch, born in

Saxony, Germany and their eight children,

ages 3 to 17 were Larch Avenue residents.

Although their names, ages, gender,

profession, place of birth and color as “W"

for white are all listed in the census, their

exact address was not recorded in the census.

The 1861-62 Jersey City Directory lists Joseph Gavenesch’s address as a house on 3rd Avenue, now known as Larch Avenue.

|

Click to view larger image

A deed shows the transfer of property

A deed shows the transfer of property

from the Town of Hudson Land

Association to Joseph Gavenesch for

$1,157 on April 2, 1860.

|

A later census

places the Gavenesch home at number 85 Larch, one of the other lots that Joseph had purchased, so we do not know who lived at number 77 in the early

years. A dwelling on Lot 84, or 77 Larch Avenue, is depicted in the 1873 Combined Atlas of the State of New Jersey and the County of Hudson, but the

exact date of its construction is not known.

|

Click to view larger image

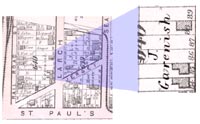

Detail from the 1873 Combined Atlas of

Detail from the 1873 Combined Atlas of

the State of New Jersey and the County of

Hudson, “J. Gavenesh” owned six lots, with

dwellings on Lot 84, which later became

77 Larch, and on Lots 85 and 88.

Gavenesch lost his property to the Equitable Life Assurance Society in 1879. The bank continued to rent out the house at 77 Larch for many years.

The 1880 Federal Census lists 36-year-old Edwin and 28-year-old Rebecca Barsa, Welsh Americans from Virginia and Philadelphia and their three

children as residents of 77 Larch Avenue. Twenty-six year-old Horace Colvin, a boarder from Ohio, was living with the Barsas at this time. Irish-born

John Dowd, 31 years old, his 30-year-old wife Mary and their two New Jersey-born daughters Annie and Mary were listed as a separate household in the

same dwelling. It is likely that Joseph

|

Click to view larger image

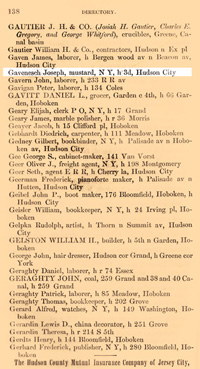

A page from Gopsill’s Jersey City,

A page from Gopsill’s Jersey City,

Hudson City and Hoboken Directory for

1864-1865 shows Joseph Gavenesch,

a mustard dealer, living on “3d, H C”

or 3rd Street, Hudson City, which

later became Larch Avenue.

Hudson City was later incorporate

into Jersey City. |

Gavenesch built 77 Larch as a two-family dwelling, with one apartment on each floor. The house always had at least two separate families, and often extra

boarders. The Barsas and Dowds were not found in the 1880 Jersey City directories. Horace Colvin was listed in 1880 as a driver living at 77 Larch,

but he did not appear in the directories for other years.

The 1890 Federal Census was destroyed by a fire at the Commerce Department in Washington, D.C. on January 10, 1921. The 1885 and 1895 New Jersey

State Censuses were examined to fill in the gap between 1880 and 1900. Henry Beck and Frank Altvatter, who we know from independent sources as

residents of 73-75 Larch Avenue, were located in the 1885 State Census.

This brings us to the vicinity of 77 Larch. Census takers did not always go from one house to the next along a street -- sometimes they crisscrossed

a street, and sometimes they returned to a house when no one was home on their first visit.

The addresses of the men who were listed near Beck and Altvatter -- Julius Clements, John Hooker, Daniel Tiedeback, and John Ring -- were checked in

city directories in and around 1885. Jules Clements, a butcher, who was listed at 75 Larch in those years, was probably renting the Becks’ small

house. John Hooker was listed at 77 Larch in 1885 and 1886, as was Daniel Tiedeback. John Ring, a machinist, was listed at 77 Larch in 1882, 1883,

1885, and in every city directory until 1892. A combination of the censuses and the directories has filled in our picture of who lived at number 77.

The pattern of the absentee landlord and a frequent turnover of tenants would soon come to an end. In 1892, Dominico Balbo bought the property, and

soon after he and his family moved in to the house. The Balbo family remained in the house into the 21st century, renting out the other apartment.

|

Click to view larger image

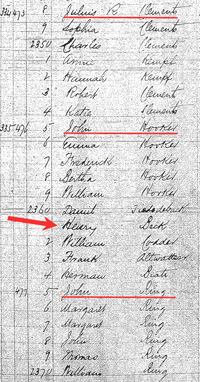

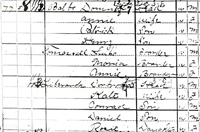

A detail from a page of the 1885 New Jersey State Census, although hard to read, shows Henry Beck, who we

know lived at 73 Larch Avenue. The detail also shows that Julius Clements, John Hooker and John Ring (underlined in red) headed households.

A detail from a page of the 1885 New Jersey State Census, although hard to read, shows Henry Beck, who we

know lived at 73 Larch Avenue. The detail also shows that Julius Clements, John Hooker and John Ring (underlined in red) headed households.

Click to view larger image

The deed, dated June 20, 1892, for the

The deed, dated June 20, 1892, for the

sale of 77 Larch to Dominico Balbo shows

a sales price of $1,500 and the property’s “metes and bounds” highlighted in white.

|

There is some confusion about exactly when the Balbos moved to 77 Larch, because Dominico was not listed here in the directories until 1897, and

there was no Balbo family listed here in the 1895 New Jersey census. A careful comparison of the 1895 New Jersey State Census and the 1900 Federal

Census and the realization that foreign names often were recorded incorrectly, may lead to an explanation.

|

The 1895 New Jersey State Census listed two families, the Meolas and Barbas, as residents of 77 Larch. Thomas and Annie Barba were listed with two

children, Patrick and Millie, both under 5 years old, and Nellie Barba, a woman more than 60 years old. Nellie, it seems, was accidentally listed

with the next-door neighbors at the bottom of the previous page in the census. It is possible that the Barbas were actually the Balbos.

The census taker may have understood the owner’s name was Tom for Thomas instead of Dom for Dominico, and Balbo may have been understood as Barba.

If this is the case, then the Balbos had moved into their house at 77 Larch by 1895, with tenants Antonio and Kate Meola and their children, George

and Jessie as tenants.

Thirty-year-old Dominick – his name anglicized by the census-taker – and his 25-year-old wife Annie, or Angela or Angelina Balbo, both born in Italy,

were counted in the 1900 census at 77 Larch

|

Click to view larger image

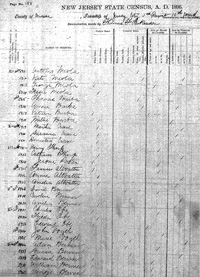

A full page from the 1895 New Jersey

A full page from the 1895 New Jersey

State Census shows the Meolas and

Barbas in a house that was probably

at 77 Larch Avenue. Note their

neighbors were the Thorpes and

Altvatters. Because of the similarities in name and the age of their children,

Thomas and Annie Barba may actually

have been Dominick and Annie Balbo

as listed in the later 1900 census.

|

with their children, 6-year-old Patrick or Pasquale and 2-year-old Henry. If the Balbos and Barbas were

one and the same family, both the daughter Millie and her grandmother Nellie must have died in the years between the 1885 and 1900 censuses.

The Balbos had boarders and tenants in 1900. The Thomascells -- Lupo, 34 years old, and Maria, 25 years old and

their daughter Annie, 5 years old, all from Italy -- boarded with the Balbos. Lupo was listed as a laborer.

In the other apartment lived the Liberardas: husband Dorbroda, 37 years old, who was a carpenter, his wife Kate, and their three children. The

Liberarda sons, Conrad, 16, and Daniel, 14, worked as a blacksmith and a shoemaker, respectively. Daughter Rosie, 12, did not work. All of the

Liberardas were born in Italy.

Dominick Balbo became a grocer in 1910, but continued to rent out the apartment in his house to immigrant families who worked in the local factories.

Angela lived until 1958, and the house then passed to her oldest son Pasquale, who had been listed in censuses as Patrick, and her youngest daughter

Anna Balbo Colaneri. The Colaneris lived in the house until it was purchased by the New Jersey Department of Transportation in 2005 to clear the way

for eventual road construction.

|

Click to view larger image

A detail from the 1900 Federal Census

A detail from the 1900 Federal Census

shows that the Balbo, Thomascell, and

Liberarda families, all from Italy,

lived at 77 Larch Avenue.

The Balbo house at 77 Larch Avenue

The Balbo house at 77 Larch Avenue

was still standing in 2006. Dominic

Colineri, the grandson of Dominic Balbo, sold it to the New Jersey Department

of Transportation so that it could

be demolished in 2007 in preparation

for construction of new ramps and

the replacement of the St. Paul’s

Avenue Viaduct.

|

Archaeology

Where are archaeological sites with deposits of early artifacts likely to be found? One of the important decisions archaeologists make is where to

dig. By studying early maps and deeds, researchers can often determine |

when houses were first built on each lot in an urban area. The first houses on Covert Street, Larch Avenue, and Seaman Avenue were built in the

1860s, 70s, and 80s. But it does not necessarily follow that these yards will contain buried trash deposits of interest to archaeologists.

One of the key pieces of information guiding research in urban settings is when utility lines were available to early residents. Before water lines

and sewers were laid in the streets, houses had to have their own accommodations – wells and cisterns for water, and of course outhouses or

“privies.” Privies sometimes were small with unlined or wood lined shafts, and sometimes were more permanent, with stone shafts, and were cleaned

out periodically. When people hooked up to water they no longer needed their wells and cisterns, and |

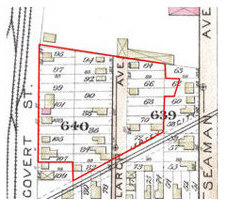

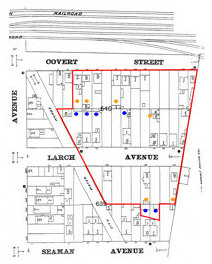

Click to view larger image

1896 Sanborn map of lots in the Covert/Larch Historic District. Lots with potential for archaeological deposits

are indicated by

colored circles.

|

when they hooked up to the sewers they abandoned their

privies. Residents often used the empty shafts for handy trash disposal. Such trash deposits provide archaeologists with excellent collections of

artifacts from individual households.

To find out whether the properties on Covert Street, Larch Avenue, and Seaman Avenue had houses that pre-dated utilities, researchers visited the

Jersey City Free Public

Library and consulted the Annual Report of the Board of Public Works of Jersey City, the Manual of the Board of Street and Water Commissioners of

Jersey City, and the Report of the Chief Engineer of Jersey City. Water lines were laid in Seaman and Covert Streets in 1872, and in Larch Avenue

sometime before 1887. Sewers were laid somewhat later: 1895 in Larch Avenue, 1903 in Seaman. On Covert Street no sewers were provided until the

1970s, so households turned their privies into septic tanks once indoor plumbing was introduced.

Lots were targeted for archaeological testing based on when the first houses were built, and when utilities were available – in other words the

researchers were able to make informed decisions about the likelihood that rich deposits of household refuse would be found in any given backyard.

Fieldwork |

| A backhoe was used to strip away upper layers of fill soil, down to the old, buried surface layer or to the tops of old shafts. The exposed area

was mapped, and as new features appeared they could be added to the map. Sometimes old privies appeared simply as stains in the soil, suspiciously

regular in shape. Some of these privies were lined with rotted wooden planks. Once a shaft was located, a portion of it was excavated by hand,

using shovels and trowels and sifting the soil through wire mesh, to determine the type of deposit within it. |

Initial clearing of road construction

fill in order to expose buried

historic backyard features. |

| Soils were excavated one stratum (layer) at a time, since distinct layers may represent successive episodes of refuse disposal.

Artifacts were placed in bags labeled with the site designation (in this case the address), the number of the excavation unit, and a consecutive

number representing the soil stratum. |

Some of the lots could not be tested due to the difficulty of excavating them with machines – either the yards were blocked off by other buildings or

there were sheds covering yard areas. These properties will be revisited in the upcoming field program.

Preliminary results

So far, it has been determined that significant deposits -- that is, deposits with enough artifacts to contribute to research on 19th-century

material |

Opening view of buried historic privy. Note later drainpipe leading into earlier feature indicated by dark stain on surface.

Opening view of buried historic privy. Note later drainpipe leading into earlier feature indicated by dark stain on surface.

|

culture -- are present in the yards behind four houses on Larch Avenue. For the most part, these deposits are in abandoned privy

pits. Two more backyard areas, for houses that once stood along Seaman Avenue, were tested and also have yielded artifact-rich abandoned privies.

Sites have been given names (based on their historic occupants) and official Smithsonian site numbers. The numbers are used to register the sites

with the New Jersey State

Museum, and include the number “28” for New Jersey, the letters “Hd” for Hudson County, and a unique, sequential number. The six identified

sites are thus sites 20 through 25 for Hudson County, New Jersey.

|

| Historic Name |

Site Number |

Address |

Beck/Thorpe/Altvatter House and Tenant

House Sites |

28-Hd-20 |

73-75 Larch Avenue |

| Gavenesch/Balbo House/Store Site |

28-Hd-21 |

77 Larch Avenue |

| Gavenesch/D’Amato House/Saloon Site |

28-Hd-22 |

79 Larch Avenue |

| Gavenesch/Sarno House Site |

28-Hd-23 |

85 Larch Avenue |

| Radcliffe/Hoersch House Site |

28-Hd-24 |

Formerly 23

Seaman Avenue |

| Moore/Bukowski House Site |

28-Hd-25 |

Formerly 25

Seaman Avenue |

| One of the discoveries made by archaeologists at these sites is that most of the lots had more than one privy. There were sequences

of two or more small, relatively shallow, wood-lined privies. Each privy was |

Profile views of excavated privy

Profile views of excavated privy

at 23 Seaman Avenue. |

apparently filled with trash upon abandonment. This means that even for Covert Street, an earlier set of privies may have been abandoned and

filled with trash, even if the later privies were built more substantially and remained in use as septic tanks. So, though Covert Street was

initially thought to have no archaeological potential, the testing plan was revised, and lots on that street have now been added to the target

sample.

|

Six additional yard areas have been selected for testing, which will be accomplished once all of the residences and businesses have

been vacated. The sites will receive registration numbers if they prove to contain important archaeological deposits.

|

What can we learn?

The significance of the archaeological deposits stems from their collective potential to shed light on the culture(s) of a working class community in

the late 19th century. Excavations in the Covert/Larch Historic District will make possible detailed comparative research on the material culture of

individual households. The items discarded in each trash deposit may differ along with differences between households in terms of the occupations of

household members, national origin or ethnic identity, and wealth.

While property records, censuses, and directories provide information about who owned and resided in these houses during most of the 19th and early

20th centuries, such documentary sources say nothing about how these people lived, differences in life-style among the various families, and how

their ways of |

Food remains (above) and

Food remains (above) and

food containers (below)

recovered from backyard

features at 23 Seaman Avenue.

|

life may have changed over the course of time. The period of the 1860s through 1890s was particularly important in the development

of American “consumer culture.” What we want to explore is the role of immigrant families from diverse cultural backgrounds in the formation of an

American working class dependent on consumer goods.

|

Comb, cologne bottles and cosmetics recovered from backyard features at 23 Seaman and 73/75 Larch Avenue.

Comb, cologne bottles and cosmetics recovered from backyard features at 23 Seaman and 73/75 Larch Avenue. |

The material recovered includes food remains and food containers, which can be used to look at how much households may have been spending on food

or to see how food preferences differed along ethnic lines; ceramic and glass dishes, which speak to questions of style, dining practices, and

expenditure; personal items such as smoking pipes and clothing items such as buttons; toys, which may be related to changing views of childhood and

leisure; grooming/hygiene items, which might relate to how advertising, public health movements, and ideas about propriety and cleanliness related to

class status; and medicine bottles, which can indicate specific maladies, responses to illness, and the effects of mass-marketing and advertising.

Material items from stores and saloons can be examined too, to see how these establishments fit into |

the social and economic life of a neighborhood like Covert/Larch.

|

|

|

|

Tablewares (above) and decorative housewares (below) recovered from backyard features at 23 Seaman

Avenue and 88 Larch Avenue. |

|

Toys (above) and personal effects (below) recovered from backyard features at 23 and 25 Seaman

Avenue. |

|

|

|

The archaeological deposits can be used as “time capsules” to study specific households. For example, from one deposit to another, a change in

styles of dishes may reflect a change in household composition, new residents with different cultural backgrounds, or fluctuations in household

wealth.

|

|

|

Beverage (left) and medicine bottles (above) recovered from backyard features at 23 Seaman Avenue

Beverage (left) and medicine bottles (above) recovered from backyard features at 23 Seaman Avenue

and 73/75 Larch Avenue.

|

Some specific research questions were suggested when the preliminary results (from the archaeological testing phase) were reported. Examples

are:

- Did consumption patterns within the Beck/Thorpe/Altvatter households change over the generations (circa 1865 through circa 1920)? The

German-born patriarch, Henry Beck, died in 1886, but his son’s and daughters’ families continued to reside on the property. If material culture

reflects change, was this due to new products on the market, changing household composition, or changes linked to the “Americanization” of the second

generation? Did foodways, in particular, change as the older generation passed away? There were also tenant families, German and Irish immigrants,

listed in the 1880 census. Are they “visible” in the material remains?

- Two generations of the American-born Radcliffe family owned and lived at 23 Seaman from 1870 to 1894. The Moores, also American-born, resided

next door at 25 Seaman during the 1870s through 1892. How do the Radcliffe and Moore households compare to each other and to the German Beck

household?

- Did the German/German-American extended family at 73/75 Larch and the Italian/Italian-American families next door at 77 and 79 Larch differ in

consumption practices during the 1890s?

- Did the numbers of wage-earning members of a household affect the types of consumer goods present? If there were young wage-earning women in a

household, can we notice gender differences in purchases?

- Was the material culture at the Gavenesch/Sarno House distinct from that of its neighbors in the 1860s and 70s? This house was owned and

occupied by Joseph Gavenesch, who owned several other lots and worked as a mustard manufacturer and dealer in New York City. Was his family more

“middle class” than others in the community by virtue of his occupation and property, and was material culture instrumental in securing this status?

Or did his household share a more generalized “working class” status and material culture?

- The introduction of amenities in the houses on Covert, Larch, and Seaman would have been linked to the provision of public utilities. For

example, all houses predated public water and sewers, and plumbing would have been added at some point after pipes were laid in the streets. Did

tenant-occupied dwellings take longer to connect, while owner-occupants connected more quickly?

Over the coming months, we will see whether the material that is excavated can, in fact, answer these and other questions.

Archaeology Update - January 2008

In 2005 and 2006, four new historic properties were made available for archaeological testing. All four contained backyard features that required

full excavation under the agreement between the New Jersey Department of Transportation and the New Jersey Historic Preservation Office. The new sites were given

historic names and assigned site numbers by the New Jersey State Museum.

| Historic Name |

Site Number |

Address |

| Radcliff/Oechel/Bauer House |

28-Hd-33 |

88 Larch Avenue |

| Walter/Sauter House |

28-Hd-34 |

91 Larch Avenue |

| Lipfert House |

28-Hd-35 |

93 Larch Avenue |

| Radcliff/Stewart House |

28-Hd-36 |

96 Larch Avenue |

|

The deposits in the backyards were mainly abandoned privies. They were similar in some ways to those found at the other sites

in the neighborhood. The household debris found in them represents a new set of families, and the analysis will add to our picture of the

historic neighborhood.

During 2005 and 2006, archaeologists conducted full scale excavations of the old privies at the four new sites as well as the six sites that had

already been identified. Analysis of all of the artifacts recovered is under way.

The effort to record historic information included photography of all standing houses in the Covert/Larch Historic District. The 35mm black and

white photographs will be kept on file at the |

Click to view larger image

A substantially built stone-lined privy

A substantially built stone-lined privy

shaft was found at 96 Larch Avenue.

The privy had been cleaned out periodically and was later used for

trash disposal.

|

|

New Jersey Historic Preservation Office as a permanent record of the district. Digital color photographs were

also taken of the houses and architectural details. After the excavations and recordings of the houses were complete, the properties were cleared

for demolition. |

|

|

|

The architectural details of the historic houses were photographed before demolition.

|

|

|

Test excavations at three remaining sites in the historic district, all on Covert Street, took place in 2007. On these lots, however, no rich

deposits of artifacts from the early residents were discovered. This seems to be because the privies were never converted into trash receptacles --

instead, they were used continuously for drainage. The differences in how households on Larch Avenue and households on Covert Street dealt with

water and waste will be explored by looking at the archaeological evidence in light of historic research. In the late 19th century, a time when both

plumbing technology and city services were changing, variation from street-to-street and house-to-house is not surprising.

|

|

|