An Investigation Into New Jersey City University’s Financial Emergency

- Posted on - 05/18/2023

Table of Contents

Executive Summary

On June 27, 2022, New Jersey City University (NJCU or the University) declared a financial emergency and adopted an interim 90-day budget, citing a lack of funding and declining enrollment. At the request of Governor Philip D. Murphy, the Office of the State Comptroller (OSC) investigated the circumstances that led to NJCU’s financial emergency and through this report shares its findings and recommendations.

This investigation found that from 2016 through 2022, NJCU experienced steadily declining enrollment, causing NJCU’s revenues to decrease during that period. NJCU took several steps to reverse this trend and to increase enrollment, including hiring marketing consultants, increasing student scholarships to attract more students, adding undergraduate and graduate academic programs, spending more on student services, and investing heavily in real estate expansion projects. These efforts were not successful and instead served to dramatically increase NJCU’s expenses. Even before the COVID-19 pandemic hit, due to declining enrollment and increasing expenses, NJCU was already in a precarious financial position. After the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the University’s financial situation worsened.

With the University in this unstable financial position, NJCU senior administrators submitted a budget for approval by the Board of Trustees (the Board) that proposed using nearly $14 million in federal COVID-19 relief funds to pay for an existing institutional scholarship program. Through interviews and a review of more than 50,000 pages of documents, OSC found that NJCU’s former administrators were aware that using federal COVID-19 relief funding from the Higher Education Emergency Relief Fund (HEERF) to fund the existing institutional scholarship program likely violated federal law. Nevertheless, rather than presenting a budget that reflected the University’s actual financial position, the senior administrators proposed this use to the Board without informing the Board of serious potential risks. The Board adopted the proposed budget.

There is no evidence that administrators disclosed the risks to the Board of Trustees until a new interim Chief Financial Officer (CFO) was hired in April 2022, more than ten months after the budget was approved. During those intervening months, OSC’s investigation found, NJCU administrators continued to represent to the Board that the existing institutional scholarship program would be funded using HEERF funds. In reality, starting in the fall of 2021, the administration began to use the University’s cash reserves to fund the program. The administration’s failure to disclose the information to the Board and to develop a plan to address the budget gap they created resulted in a sudden declaration of financial emergency. In June 2022, the interim CFO presented information to the Board of Trustees that showed the adopted budget’s year-end projection of a $480,000 surplus would likely be a nearly $14 million deficit and that the University possessed just 25.5 days of operating cash on hand.

Additionally, OSC’s investigation found:

- The former CFO, on at least three occasions, advised the administration that the HEERF funds could not be used to pay for institutional scholarship expenses. Despite these warnings, no action was taken to correct the budget or inform the Board of the serious budgetary issues.

- The Board of Trustees failed to exercise proper oversight over the administration, especially former President Sue Henderson (the President). The Board received insufficient training and failed to appreciate its fiduciary responsibilities by not conducting a contractually-required written performance evaluation of the President. The Board also chose not to probe the causes of the financial crisis once the budget deficit became clear.

- Without exploring the causes of the financial emergency, the Board of Trustees permitted the President to resign immediately before it declared the financial emergency, with separation benefits that included a $288,000 “transitional sabbatical,” a car, and a housing subsidy.

Therefore, OSC recommends that NJCU institute changes related to budgeting and the accountability of the administration to the Board of Trustees. OSC also recommends that NJCU appoint an independent financial monitor with expertise in overseeing the finances of a public institution of higher education.

This investigation provides an example of how the decentralized structure of New Jersey’s public higher education system created an environment in which irresponsible financial decisions by administrators can go undetected by the State. As more public universities in New Jersey are facing declines in student enrollment and tuition dollars, the State’s lack of oversight poses continued risks for students and taxpayers. In view of the risks identified in this report, OSC recommends that the Legislature evaluate whether the existing oversight of public colleges and universities adequately guards against poor decisions made by administrations or boards and whether existing reporting and other requirements adequately protect the interests of students of public colleges and universities and the institutions themselves.

Background

A. New Jersey City University

New Jersey City University (NJCU or the University) is a public university established in 1927. The University’s main campus is located in Jersey City, including its School of Business located in the Harborside Financial District. In 2021, NJCU opened a branch campus 50 miles away in Fort Monmouth. At the start of this investigation, NJCU offered approximately 250 academic programs housed across four colleges. Its stated mission is to provide “a diverse population with an excellent education” and to improve “the educational, intellectual, cultural, socioeconomic, and physical environment of the surrounding urban region.”

As of fall 2021, NJCU had 5,262 undergraduate students.[1] NJCU is a majority-minority institution. As of 2021, the undergraduate population is 45 percent Hispanic/Latinx, 21 percent Black/African-American, 18 percent White, and 8 percent Asian.[2] Most NJCU students are economically disadvantaged; 58 percent receive federal Pell Grants.[3] The overwhelming majority of the University’s students are New Jersey residents.

B. Public Institutions of Higher Education Increasingly Rely on Student Tuition Revenue amid Declining Enrollment

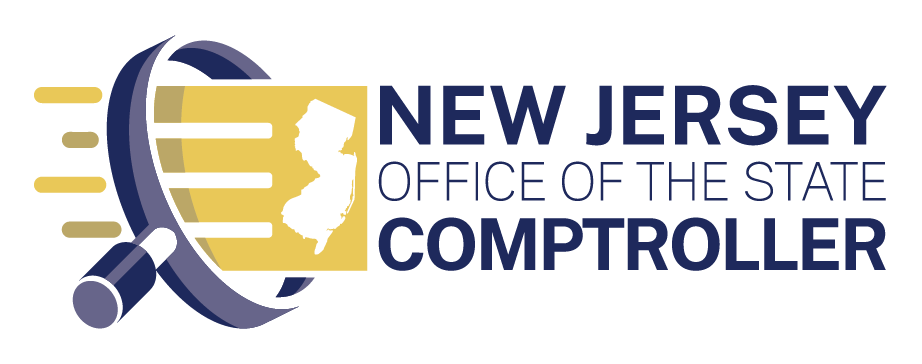

The two primary sources of funding for public institutions of higher education are state appropriations and student tuition revenue. Since the 1980s, the student share of public higher education costs has increased significantly nationwide. In New Jersey, the student share rose from roughly 20 percent in 1980 to 49 percent in 2021.[4]

Figure 1: Student Share of Public Higher Education Costs Increase between 1980 and 2021.

Source: State Higher Education Finance, 2021 SHEF Report

But over the past ten years, enrollment in higher education has been declining nationwide. Between 2011 and 2021, nationwide enrollment dropped by 12.7 percent. In New Jersey, enrollment declined over that period by 13.7 percent. Industry experts attribute nationwide waning enrollment to a number of factors, including lower birthrates, an improved economy, and increased tuition rates.

The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated the trend, bringing steep declines to higher education enrollment across the nation. In 2021 alone, nationwide enrollment at public institutions of higher education declined by 3 percent, the largest single-year decline on record. In New Jersey, enrollment in public four-year institutions fell by 6.1 percent in 2021, double the national average.

C. The Decentralized Public Higher Education System in New Jersey

New Jersey operates under a decentralized public higher education system. Beginning in the late 1960s, the Legislature enacted a statutory framework that gave public colleges and universities “a high degree of self-government.” While the Board of Higher Education within the Department of Higher Education had some supervision, the control, conduct, management, and administration of institutions was left to the boards of trustees.

The higher education system was transformed in 1994 with the passage of the Higher Education Restructuring Act (HERA), which sought the “elimination of unnecessary State oversight and its accompanying bureaucracy.” HERA abolished the Board of Higher Education and Department of Higher Education and allocated all aspects of institutional governance to the boards of individual state colleges and universities.[5] HERA also established three new bodies to provide limited statewide coordination of the state’s higher education system: the Commission on Higher Education (CHE), the New Jersey Presidents’ Council, and the Office of Student Assistance.

In the three decades since HERA’s passage, New Jersey’s public colleges and universities have operated essentially autonomously, though the state-level structure has continued to evolve. In 2009, the Legislature effectively replaced the director of CHE with a new cabinet-level position, the Secretary of Higher Education (the Secretary). Two years later, the Governor executed a reorganization plan that abolished CHE and transferred its authority and responsibilities to the Secretary.[6]

Under the current approach, although it has limited regulatory powers, the Office of the Secretary of Higher Education (OSHE) is primarily focused on policy development and the statewide plan for higher education. In its regulatory capacity, OSHE is responsible for issuing final administrative decisions regarding institutional licensure, reviewing whether schools may obtain university status, reviewing changes to an institution’s programmatic mission and degrees awarded, and reviewing the creation of new academic programs. With limited exceptions, these functions provide OSHE with opportunities to review, but not supervise or intervene in, an institution’s operations.

OSHE’s duties have expanded somewhat over the years, but the higher education system remains largely decentralized. For example, since 2009, all licensed higher education institutions have been required to retain an outside auditor to conduct an annual audit and submit an audit report to OSHE. But the law does not authorize or direct OSHE to take action based on the information contained in an institution’s annual audit report.[7]

In 2021, the Legislature assigned OSHE additional responsibilities, including modifying OSHE’s role in reviewing new academic programs, approving branch campuses within the state, and monitoring a non-public institution’s risk of closure. [8]

D. Governance of Public Institutions of Higher Education

1. Board of Trustees

“The government, control, conduct, management, and administration of each of the [public institutions of higher education] shall be vested in the board of trustees,”[9] whose powers are broad and exercised largely without state supervision.

The board adopts the institution’s bylaws and establishes its organizational, administrative, and developmental policies. It is responsible for developing an institutional plan and determining the college’s educational curriculum and program, as well as setting admission and graduation standards.

The board of trustees is authorized to make personnel decisions, including appointing the university president and setting the president’s compensation. The board may dismiss the president at any time. Although the president nominates members of the academic and administrative staff, the board is responsible for appointing individuals to these positions and setting their compensation and terms of employment.

The board of trustees also controls the institution’s finances, property, and contractual obligations. The board is required to study the financial needs of the college and prepare and present its annual budget to the Governor’s Office, the Legislature, and the Division of Budget and Accounting within the Department of Treasury. The board sets tuition rates, student housing rates, and other fees, and accepts any government grants or private contributions of money or property on behalf of the college.

The board also directs the expenditure and disbursement of college funds, including state appropriations and tuition revenues; awards contracts for goods and services; and arranges for the payment of all expenses. It may borrow money on behalf of the college and direct the investment of the college’s funds. The board is authorized to acquire real property and arrange for the planning and construction of buildings necessary for the college.

By law, board members must complete a training program that clarifies their roles and duties. Each institution of higher education develops the training for its respective board.

2. The University President

The president of a state college or university is responsible for the executive management, conduct, and administration of the institution. The president ensures the execution and enforcement of the bylaws, rules, and regulations governing the institution. All departments and offices within the institution report to the president. State statute empowers the university president to perform these broad functions but does not enumerate specific obligations.

The president reports to the institution’s board of trustees and serves as a non-voting, ex officio member of the board. As such, the president is responsible for apprising the board of university operations and presenting the board with proposals for major projects or initiatives requiring its approval. As a practical matter, the president also serves as the public face of the institution.

3. NJCU's Board of Trustees

The bylaws governing NJCU’s Board of Trustees (the Board) are consistent with its statutorily prescribed powers and responsibilities. The Board has two elected officers: the Chair and the Vice-Chair. The Chair presides over all board meetings and has general supervision over board affairs. NJCU’s Board of Trustees has five standing committees: the Executive Committee; the Finance and Audit Committee; the Nominations and Governance Committee; the University Mission Committee; and the University Business, Planning and Infrastructure Committee. Both the Chair of the Board and the University President are ex officio members of each standing committee.

Methodology

For this report, the Office of the State Comptroller (OSC) reviewed and analyzed over 50,000 pages of documentation and information concerning NJCU’s finances, enrollment, operations, academic programs, and internal policies. OSC reviewed NJCU’s budgets and financial statements, internal and third-party reports, projections, and internal and external communications, among other materials. OSC also reviewed publications and best practices regarding university governance and finances. The investigation also involved the review and analysis of applicable statutes, regulations, and case law.

As part of this investigation, OSC conducted approximately 30 interviews. OSC interviewed current and former members of NJCU’s Board of Trustees, administration, staff, and faculty. Some of the individuals were interviewed on multiple occasions. Additionally, OSC interviewed NJCU’s external auditor, representatives from other public institutions of higher education within New Jersey, and representatives from OSHE. OSC also reviewed materials provided by those representatives.

OSC sent full drafts or relevant excerpts of this Report to NJCU, including current and former members of its Board of Trustees and administration, NJCU’s external auditor, and OSHE to provide each recipient with an opportunity to comment on the facts and issues identified during this review. In preparing this report, OSC considered the responses received and incorporated them where appropriate.

Findings

OSC’s investigation found that NJCU experienced a continued decline in its financial position resulting from a combination of decreases in enrollment and increases in spending as it entered fiscal year 2022. In the midst of this financial decline, NJCU administrators budgeted approximately $14 million of federal COVID-19 funding to support a pre-existing scholarship program, knowing that such a use was likely unlawful. The administrators failed to inform the Board of this fact and failed to take corrective action, thus creating a budget crisis in the spring and summer of 2022.

OSC’s investigation found that weaknesses in governance may have contributed to the crisis. NJCU’s governing Board of Trustees received inadequate training and exercised insufficient oversight of the President. The decentralized structure of the State’s public higher education system, which places substantial control in boards of trustees and limits state involvement, may increase the risk of such crises happening again in the future.

A. Historic Declines in Student Enrollment and Increases in Expenditures Weakened NJCU's Financial Position as the University Entered Fiscal Year 2022

As part of this investigation, OSC analyzed trends in NJCU’s revenues and expenses from 2011 through 2021. Net student revenue—the primary source of NJCU’s funding—decreased over time due to declines in student enrollment. The other source of NJCU’s funding—state appropriations—also decreased during this period. At the same time, investments by the University made in response to those enrollment declines and expanding salary obligations increased its expenses. These factors weakened NJCU’s financial position leading into fiscal year 2022.

1. Significant Enrollment Declines Impacted Net Tuition Revenue

Tuition revenue received from students has historically been NJCU’s primary source of operating revenue; it comprised an average of 60 percent of NJCU’s operating revenue from 2011 through 2021. NJCU has raised tuition an average of three percent every year since 2011. But while total tuition revenue over this period increased by approximately $20 million, NJCU’s net tuition revenue only increased by a modest $1 million, at least in part because of increased expenses associated with tuition discounting programs (e.g., scholarships).

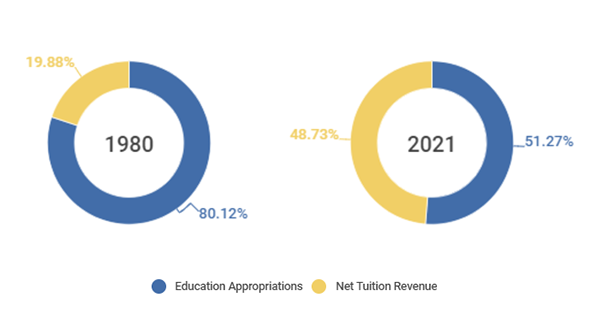

NJCU’s enrollment data shows that the University experienced a protracted enrollment decline that exceeded the national average. Between 2011 and 2021, total enrollment at NJCU declined from 8,328 to 6,918 students, a decrease of 16.9 percent. The majority of this decline was from NJCU’s undergraduate population. By contrast, enrollment at institutions of higher education declined by 12.7 percent nationally over this same period.

Pandemic era declines were particularly severe at NJCU, where enrollment dropped 12.4 percent in the three years from 2019 to 2021 alone. Again, most of this decline was among undergraduates, although graduate enrollment also dropped by 8.6 percent over that same period.

Figure 2: Even Before the Pandemic, Student Enrollment at NJCU was Declining

Source: National Center for Education Statistics, Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System

Source: National Center for Education Statistics, Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System

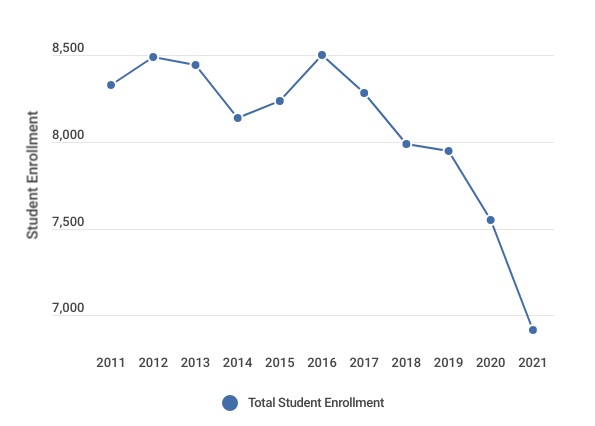

A decline in the enrollment of transfer students from area community colleges was a primary factor contributing to NJCU’s enrollment decline and, by extension, its financial distress. Several NJCU representatives asserted that NJCU disproportionately served transfer students and was impacted by overall declines in the community college student population. NJCU’s enrollment figures confirmed the reduction in transfer students enrolling at the University, showing a significant drop in transfer students after 2016. While the number of first-time students increased modestly after 2016, as shown in the figure below, any gains in first-time students did not offset the loss of transfer students.

Figure 3: Total Enrollment Dropped Due to Declines in Transfer Students

Source: National Center for Education Statistics, Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System

NJCU’s Vice President of Enrollment Management (Enrollment VP) attributed this decline to lower enrollment at New Jersey community colleges overall. A review of enrollment statistics for New Jersey’s community colleges between 2011 and 2021 confirmed significant declines in enrollment, averaging 31 percent over the time period.[10]

The Measures Implemented by NJCU to Reverse the Enrollment Decline Proved Unsuccessful

NJCU implemented a number of recruiting efforts to improve enrollment, including strengthening its partnerships with community colleges, prioritizing the applications of full-time students, increasing the amount of scholarships awarded, and targeting high-achieving students for enrollment. None of the measures proved successful.

NJCU’s Enrollment VP stated that the decline in the number of transfer students attending NJCU was the subject of weekly meetings with former President Sue Henderson's (the President) senior team, and that the University strengthened its partnerships with community colleges in an attempt to address that decline. Specifically, NJCU modified its agreements with the community colleges that provided the majority of its transfer students so that NJCU’s programs were better aligned with the community college programs. This measure was ultimately unsuccessful in reversing the transfer student decline.

In response to the declines in transfer students enrolling at the University, NJCU also began to target full-time over part-time students. NJCU took this approach because the market for full-time students was not declining, whereas many part-time students were transfer students, and that population was declining. NJCU also focused on full-time students because part-time students have minimal financial aid eligibility.

OSC spoke to the most recent as well as the former Enrollment VP; both stated that, in an attempt to boost enrollment, NJCU hired consultants beginning in 2015 to determine if NJCU’s financial aid awards were in line with competitors. One of the Enrollment VPs stated that NJCU began to increase its scholarship awards to remain competitive with other universities and increase enrollment. He further stated that an analysis performed at that time showed that a majority of applicants admitted by NJCU chose to attend community colleges rather than NJCU. He explained that this was because NJCU offered low scholarship awards and the actual cost of attendance was more expensive than both community colleges and competing four-year institutions.[11]

The former Enrollment VP claimed the increased scholarships were also weighted more toward higher academically performing students because those students retain and graduate at higher rates. A review of NJCU’s graduation and retention rates showed the University achieved modest improvements in both of those areas after 2015. These improvements to the graduation rate impacted enrollment, however. As the average time to graduate shortened, the current student population would decrease until the graduation rate and enrollment stabilize. This resulted in a negative impact to NJCU’s current overall enrollment, and thus its primary source of revenue.

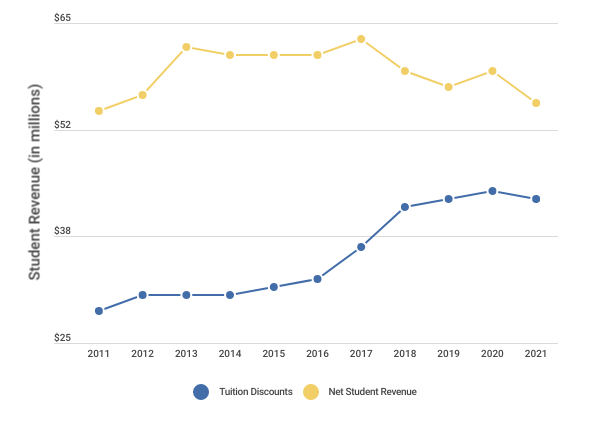

NJCU’s enrollment data shows that enrollment increased through 2016 before beginning to decline. Similarly, net student revenues grew through 2017 before beginning to decline. But increasing scholarship expenses—which were effectively tuition discounts—continued to impact net student revenues.

Figure 4: Reliance on Tuition Discounts Reduced Net Student Revenue

Source: New Jersey City University, Audited Financial Statements

While net student revenue increased very modestly between 2016 and 2017, growth ceased after that date, demonstrating that the scholarship policy did not effectively increase tuition revenue. The Enrollment VP stated there was a learning curve associated with the scholarship policy and that there had been frequent discussions at NJCU about the sustainability of that policy. The Enrollment VP maintained that the scholarship amounts were necessary to attract NJCU’s low-income students and expressed his opinion that NJCU would have experienced financial distress even sooner than it did without those tuition discounts.[12]

Further compounding NJCU’s financial difficulties, these tuition declines came during a time of essentially static state funding for the University. Appropriations from the State fell slightly from 2011 to 2021, from $27 million to $26.7 million. For four years during this period, state appropriations were $24.2 million, and in one year, appropriations dropped as low as $21.5 million.

2. Increased Expenses Further Weakened NJCU’s Financial Position

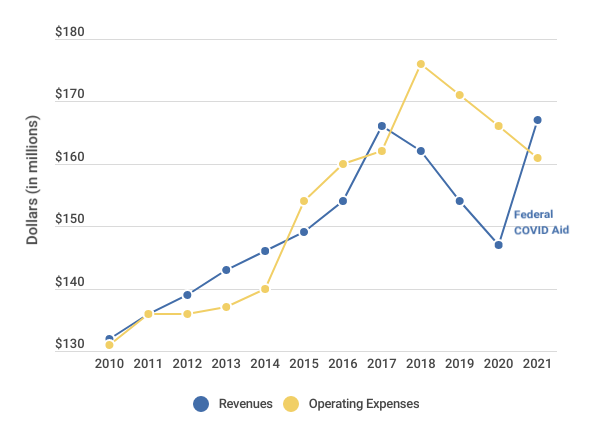

While enrollment declined from 2011 to 2021, NJCU’s operating expenses increased. This placed NJCU in a continually worsening financial position, with the University experiencing multiple years of budgetary deficits as it entered fiscal year 2022. The increased expenses were tied to enrollment and scholarship initiatives, increased instructional costs, and costs associated with expansion of the University. The figure below tracks NJCU’s total revenues and expenses over time; particularly noteworthy is the decoupling of these two figures from one another after 2017. Although revenues appeared to recover sharply in 2021, that figure includes millions of dollars in COVID-19 relief funding. As discussed later in this report, that aid was temporary, with only a portion reserved for the University’s use, and subject to regulations that limited when and how it could be used.[13]

Figure 5: Operating Expenses Far Exceed Revenues Beginning in 2018

Source: New Jersey City University, Audited Financial Statements

NJCU Increased Spending on Enrollment and Student Services

In an effort to attract more students, NJCU expanded its recruiting efforts, hired additional staff, and engaged additional consultants. In 2015, the first year these steps were taken, NJCU spent approximately $1.7 million on those services. With the exception of the 2018 financial report, financial reports from 2015 to 2020 show that expenses associated with recruiting and retaining students increased by an average of $1 million annually.[14]

In an attempt to boost enrollment and retention through improvements to campus life and student success, NJCU also significantly increased its spending on student services. This category typically includes expenses related to athletics, student organizations and events, and other extra-curricular activities. Spending in this category rapidly grew from $14 million in 2011 to a high of $23 million in 2018. Although spending on student services decreased slightly by 2021, dropping to $20.5 million, that number still reflects an increase of 46 percent from the 2011 figure.

NJCU Incurred Significant Costs in Expanding its Academic Programs, But Did Not Evaluate Whether the Programs were an Effective Use of Resources until April 2021

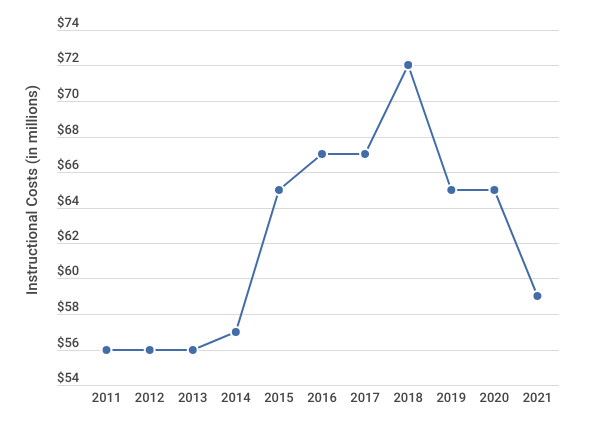

Increased instructional costs, a category that includes faculty salaries and the costs of creating new instructional programs, also affected NJCU’s financial position.[15] As shown in the figure below, these costs grew from $56 million in 2011 to a peak of $72 million in 2018, then dropped back down to $59 million in 2021. The steep increase in instructional costs coincided with a dramatic expansion of NJCU’s academic offerings. In less than ten years, NJCU increased the number of undergraduate minor programs offered from just 6 in 2011 to 50 in 2020. Likewise, from 2013 to 2020, NJCU increased the number of master’s degree programs from 29 to 54. As the data reflects, this expansion came at a significant cost to the University. One NJCU administrator explained that adding new academic programs is an expensive process because it requires full-time faculty to focus their efforts exclusively on program development instead of teaching. The vacancies in teaching positions stemming from academic expansion must then be filled with adjunct faculty.

Figure 6: Instructional Costs Peak in 2018

Source: New Jersey City University, Audited Financial Statements

Beginning in April 2021, a consultant engaged by NJCU evaluated the University’s academic undergraduate and graduate offerings and found that the vast majority of students were clustered in a minority of programs. Seventy-one percent of undergraduate students—or nearly 3 out of every 4—were enrolled in just 15 of the University’s programs. The report’s review of graduate level programs demonstrated even greater concentrations of students in a limited number of programs. According to the report, 15 graduate-level programs awarded 80 percent of graduate degrees. Even more striking, five graduate-level programs—special education teaching, counseling, accounting, educational technology, and health sciences—awarded nearly one half of graduate-level degrees.

According to several NJCU administrators, in the face of reduced enrollment, falling revenues, and decreased state aid, NJCU did not take steps to evaluate the financial impact of its academic offerings between 2008 and April 2021. These individuals told OSC that the University did not eliminate any programs or degrees from 2008 to 2021, though former President Henderson told OSC she instituted a review process for that purpose. When OSC spoke with the current administrator in charge of academic programs, however, she stated there was no system in place to conduct such a review or any written policies or procedures on the subject.[16]

Increased Real Estate, Bond-related, and Capital Expenses

NJCU began incurring significant real estate expenses in 2016, marking a departure from the prior year’s expenses. While the 2015 financial statement identified $91,000 in real estate expenses, that number jumped to $4.3 million in 2016, an increase of approximately 4600 percent in a single year. From 2016 to 2021, financial reports show an average of $3.5 million in annual real estate-related expenses. These expenses primarily resulted from the opening of NJCU’s School of Business in a leased facility as well as the development of University Place. Additionally, the opening of a branch campus at Fort Monmouth was set to increase this expense by an additional $1.6 million per year at the start of fiscal year 2022, which commenced on July 1, 2021.[17] Relatedly, the expenses associated with operating all of NJCU’s facilities increased from $15.6 million per year in 2011 to $18.5 million per year in 2021, an increase of approximately 19 percent. NJCU also made significant investments in capital assets such as land, buildings, and equipment from 2011 through 2021. Between 2013 and 2019, NJCU had average cash outflows of $19 million per year related to the purchase of capital assets.

Although the University was able to acquire capital grants from the State and unearned capital reimbursements from Jersey City to finance some of these costs, the University was responsible for certain portions of the funding. The financial statements indicate NJCU obtained this funding through the issuance of debt in the form of bonds.

Although the issuance of bonds provided a temporary influx of cash to the University in exchange for debt, the cost to service the debt has amounted to an ongoing and increasing expense. OSC reviewed NJCU’s cash flows from 2011 to 2021 and noted the interest paid on capital debt increased from $5.5 million to $9.8 million, an increase of 78 percent. Increases on capital debt principal payments grew by 65 percent over that time period, from $4.3 million to $7.1 million, and the future cost to service these bonds is projected to increase further. NJCU has also continually issued new bonds to refund the debt associated with previous bonds, which defers, rather than addresses, the accumulation of debt by the University.[18]

NJCU’s Net Position and the Impact of Government Accounting Standards Board Statement Number 68

When evaluating the overall impact of these expenses to NJCU’s net financial position, it is important to note that the adoption of Government Accounting Standards Board Statement Number 68 (GASB 68) gave the appearance of having a tremendous impact to NJCU’s finances. This accounting standard, adopted in 2015, requires NJCU to record the costs associated with its employee pension plans on its own financial statements. Previously, these costs would not have been reflected on NJCU’s financial statements. After the adoption of GASB 68, however, the University must now record this cost on its balance sheet, even though the State continues to make the payments.

Even accounting for the impact of GASB 68’s adoption, NJCU’s net position continued to decline for reasons unrelated to that accounting standard and instead attributable to both decreasing tuition revenue combined with steadily increasing expenses. After removing the liability attributable to GASB 68, NJCU’s net position declined from $104 million in 2015 to $69 million in 2021, a drop of 34 percent.

B. Improper Budgeting Caused NJCU to Declare a Financial Emergency

Against the backdrop of this declining financial position, NJCU’s administrators made a series of decisions that resulted in the declaration of a financial emergency. The University planned to improperly fund approximately eight percent of the expenses in the 2022 budget—nearly $14 million—using federal COVID-19 relief funding from the Higher Education Emergency Relief Fund (HEERF). NJCU’s planned use of these funds—to fund existing institutional scholarship expenses—violated restrictions on the use of the funds. At the time they presented the budget to the Board, and for months thereafter, NJCU’s administrators knew that federal law likely prohibited them from using the funds for the purpose identified in the budget.

Nevertheless, NJCU’s administrators submitted this budget to the Board of Trustees, which adopted the budget on June 28, 2021. NJCU’s administrators did not notify the Trustees that the planned use of these funds violated federal restrictions nor did they take any corrective action until a new CFO was hired, more than ten months later. Rather, the administration used the University’s cash reserves to fund the scholarship program’s expenses, leading to a projected year-end deficit of $13.8 million. When this deficit was finally brought to their attention, NJCU’s Board of Trustees declared a financial emergency in June 2022 and imposed deep cuts to the University’s expenses.

1. Higher Education Emergency Relief Funds and their Approved Uses

With the passage of the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (CARES) in March 2020, the federal government began providing emergency relief money to institutions of higher education through the HEERF program.[19] Additional HEERF money was provided through two subsequent grants, known as HEERF II and HEERF III, under the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2021 (CAA) and the American Rescue Plan (ARP), respectively.[20] All three tranches of HEERF funding were divided into student and institutional portions, with each portion subject to its own use requirements.[21]

According to the applicable guidelines, the student portion was required to be used by institutions to distribute emergency financial aid grants to students. Under HEERF II and III, student aid grants could be provided to cover “any component of the student’s cost of attendance, or for emergency costs that arise due to coronavirus.” Guidance documents issued by the United States Department of Education (DOE) on the use of HEERF funds consistently stated that the student portion of these grants were to be provided directly to students for use in a manner of the student’s choosing. Later guidance permitted schools to use student financial aid grants to satisfy outstanding student account balances, but only if schools obtained written, affirmative consent from students before doing so.[22]

Institutions were permitted to use their institutional portions to defray expenses associated with COVID-19.[23] At their discretion, institutions could also use their institutional portions to make additional financial aid grants to students consistent with the student portion rules above.

The size of each HEERF grant portion was specified in legislation. HEERF III required schools to use at least 50 percent of their total award on student aid grants. Critically, institutions could not use their institutional portions until and unless they disbursed financial aid grants to students. That is, if a university received a total allocation of $20 million in HEERF III funds, $10 million was required to be distributed directly to students before the university could use its $10 million institutional portion. If the institution only successfully distributed $5 million to students, the university would only be permitted to use $5 million of its $10 million institutional allocation.

NJCU received a total HEERF III grant of $24.5 million, of which $12.25 million was required by law to be disbursed as student aid grants.

2. NJCU’s Budgeted Use of HEERF II and III Would Have Violated Restrictions on Use of Those Funds

NJCU’s fiscal year 2022 budget indicates that the University anticipated receiving $27,052,832 in HEERF III funds, including a Minority Serving Institution (MSI) award.[24] Additionally, NJCU was planning to apply $3,556,495 in HEERF II money remaining from the previous fiscal year. NJCU budgeted for a $13,969,100 institutional scholarship program for fiscal year 2022. This is the same pre-existing scholarship program, discussed in Section IV(A)(1) of this report, that was used by NJCU as a tool to increase enrollment.

NJCU’s budget materials indicate that it intended to fund nearly the entire institutional scholarship program—97 percent of its projected cost—with HEERF grants.[25] Specifically, NJCU planned to use $2,514,361 of its remaining HEERF II money together with $11,054,739 of its HEERF III money to fund the program.[26] The roughly $11 million in HEERF III money came from a combination of NJCU’s institutional portion, student portion, and MSI award.

NJCU could not lawfully use any of these funds for that purpose. The institutional portion of the HEERF funds could not be used to fund NJCU’s scholarship program because (1) the funds were not being used to defray NJCU’s costs associated with the pandemic because they were budgeted to pay for an existing scholarship program, and (2) they were not being used to provide additional financial aid grants to students for emergency costs arising from the pandemic or covering the students’ costs of attendance—they were not being directly provided to students at all.

A review of NJCU’s prior year budgets and interviews with numerous representatives from NJCU confirm that the scholarship program existed prior to the pandemic and was wholly unrelated to it. The plain language of the legislation enabling HEERF grants would permit a university to apply funds to expenses associated with new scholarships that address expenses, needs, or emergency costs that arose due to COVID-19, but NJCU’s existing scholarship program did not do so. Rather, it was a pre-existing component of NJCU’s enrollment strategy. For that reason, the budgeted use of the institutional portions of HEERF II and HEERF III for institutional scholarships was improper.

This planned use was also improper for an additional reason. In order to use the funds to provide additional financial aid grants to students for emergency costs arising from the pandemic, the school would have had to distribute the funds directly to students for their own use and not for a use planned by the school.

NJCU also could not apply the student portion of HEERF III money for its institutional scholarship program for the same reasons. CAA, ARP, and DOE’s guidance required that financial aid grants to students be passed directly to students for use at the students’ discretion unless the school obtained written, affirmative consent to apply the grant to a student’s account balance. Here, NJCU improperly budgeted the use of the entire student portion of HEERF III to cover its own costs without receiving any such written, affirmative consent.[27]

Relatedly, NJCU improperly budgeted its entire institutional and student portion grants because recognition of the institutional portion depended upon disbursal of the student portion. Without first knowing how much of the student portion money could be disbursed to students or returned to the school through written, affirmative consent, NJCU had no basis for budgeting any of its institutional portion grant funds.

OSC’s investigation determined that none of the HEERF funding was spent on the University’s existing scholarship program. As discussed in the following sections of this report, however, the financial impact of failing to fund a large, structural expense or take corrective action was significant.

3. Senior Administrators Budgeted $14 Million in HEERF Funding for an Existing Scholarship Program Knowing that Such a Use Likely Violated Federal Law

Documents obtained by OSC, including internal emails from both before and after the adoption of the fiscal year 2022 budget, reveal that members of NJCU’s administration were aware that federal guidelines likely prohibited them from using HEERF funding to pay for existing institutional scholarships. Nevertheless, in June 2021, the senior administrators presented and received board approval for a budget that used the funding for that exact purpose. The decision to do so created a $14 million budget gap, further jeopardizing an institution suffering from years of financial distress.

In March 2021, NJCU learned that it would receive a projected allocation of $25 million of HEERF III funds. Between May and July 2021, emails show members of NJCU’s senior administration—specifically the former Chief Financial Officer (CFO), the President, and Enrollment VP—discussing uses of HEERF II and III funds, both of which follow the same rules for allowable uses.[28] The emails show NJCU seeking internal and external advice on permitted uses of the funds.

In one email from May 18, 2021, the former CFO forwarded the President an email in which he sought guidance from an external contact on best practices for utilizing HEERF II. In the email to the external contact, the former CFO noted that NJCU would like to apply part of the student portion of HEERF funds to scholarships and housing. The contact responded that NJCU should be able to use the student portion of HEERF funds for tuition and housing assistance if the student has a documented need. The external contact stated that NJCU could establish a student’s documented need through the use of a student survey. In an email from May 20, 2021, NJCU’s Enrollment VP shared HEERF guidance in a communication to the internal auditor, copying the President and the former CFO. In that communication, the Enrollment VP asked to discuss using the student portion of HEERF II—which followed the same rules as HEERF III—to “swap out existing scholarships rather than make direct payments to students.” He noted that the issue was “time sensitive given the budget implications.” The next day, the former CFO contacted a representative at another New Jersey public university to inquire whether that university used the funds to “swap out” an existing scholarship program—that is, whether that university used HEERF monies to fund an existing institutional scholarship program. The representative responded that the university “did not do this.”

Internal emails from late-May 2021 reveal an apparent consensus among NJCU administrators about the allowable uses of HEERF funds prior to the adoption of the budget. On May 27, 2021, the former CFO wrote an email to the President, Enrollment VP, and other senior administrators concerning the allowable uses of HEERF II. The former CFO stated “[i]n the last few weeks we have been working collaboratively to identify the allowable uses of the funding received by NJCU from HEERF Part 2.” He stated that the student portion of HEERF “should not be utilized for a scholarship initiative or a scholarship swap-out,” and then recommended that NJCU prepare to provide direct payments to students. The former CFO then recommended that NJCU prepare a calculation of its lost revenue to spend the institutional portion of the grant. Both of these recommended approaches were consistent with federal law. The President responded “Excellent.” The Enrollment VP responded with suggestions on how to calculate lost revenue.

Yet, only a month later, NJCU’s administration presented to the Board a budget for fiscal year 2022 that funded nearly the entire pre-existing scholarship program—an approximately $14 million expense—with HEERF funds.

The communications prior to the adoption of the budget indicate that the former CFO, the President, and the Enrollment VP were on notice that using HEERF to fund institutional scholarships was likely impermissible. Using the funds for such a purpose was also inconsistent with the way in which NJCU had used its prior HEERF allocations. Nevertheless, NJCU’s administrators proposed a budget that funded nearly all of its pre-existing scholarship program with HEERF III monies. The former CFO stated to OSC that he was instructed by the President to present the budget in this way. In her response to a draft of this report, former President Henderson disputed this and any knowledge that the proposed use of HEERF was impermissible at the time.

NJCU administrators engaged in similar conversations even after the adoption of the budget. The documents show that the day after the fiscal year 2022 budget was approved, the former CFO reached out to NJCU’s external auditor seeking further guidance about the appropriate uses for HEERF. In response, the auditor stated that he had little more information to provide than he did during a previous discussion with the former CFO. He ultimately declined to opine on interpretations related to allowable uses but cautioned the former CFO to “document your interpretations and who you consulted (i.e. outside counsel)” if NJCU was going to operate in “grey areas.” During this investigation, the external auditor advised OSC that he guided NJCU to review the applicable federal guidance and he also advised OSC that he did not believe federal law permitted NJCU to use HEERF funding for the existing scholarship program. He stated he did not recall NJCU staff asking him if HEERF funds could be used to fund existing scholarships and stated that he did not tell NJCU staff they could fund those scholarships with HEERF funds. The external auditor also stated he believed that, at the time, it was clear to NJCU senior administrators they had to spend the student portion before they were eligible for the institutional portion and that he did not think there was a grey area.

From July 5 to July 8, 2021, emails with the subject line “Legal opinion re: uses of HEERF funding” circulated among NJCU senior administrators. The former CFO, Enrollment VP, and others were included on these emails with internal university counsel. It is not clear what legal advice was provided through these emails and corresponding attachments, as NJCU refused to provide them to OSC.[29]

Throughout July 2021, communications related to the permissible uses of HEERF continued. On July 29, 2021, the former CFO contacted the President and Enrollment VP to discuss options related to HEERF III. He reiterated, “[b]ased on all our meetings with [the external auditor], available literature, and discussions with other NJ college/universities, the use of the ‘swap-out’ for scholarship was not considered 'best practice' for HEERF.”

In December 2021, approximately six months after the budget was approved, the former CFO again reached out to the external auditor seeking guidance about the permissible uses of HEERF funds. In an email dated December 7, 2021, the former CFO wrote an email to the President explaining the external auditor’s guidance: “we should assume that NJCU cannot utilize the HEERF Part 3 funding for Institutional Scholarship in Spring 2022.” The President responded, “I need a call at 9 am today on this. It is not serving njcu well to be making this determination at this late date.” On December 30, 2021, the President told the former CFO to prepare a new budget estimate for fiscal year 2023 and “assume that we use the COVID money for housing and other scholarships.” When asked why she would instruct the former CFO to do so despite his representation that NJCU could not use the HEERF money for existing scholarships, the President failed to provide an adequate explanation and merely suggested that information must have changed.

The documents and testimony demonstrate that the President, the former CFO, and Enrollment VP were fully aware that there were significant risks and issues involved with the budget they presented to the Board in June 2021. Internal emails show they were aware these issues persisted throughout the summer, fall, and winter of 2021 into 2022, having repeated conversations about whether using the funds for institutional scholarships was permissible.

OSC notes that the documents and testimony obtained during this investigation tell conflicting stories. In emails, the former CFO told the President and Enrollment VP at least three times that using HEERF to fund the institutional scholarship program was not advisable. NJCU’s former CFO told OSC that he budgeted the HEERF money to fund the University’s pre-existing scholarship program in the 2022 budget at the direction of the President, a fact he reiterated in his response to a draft of this report. He further made clear that this was done despite both he and the President being aware that the use of the funds in the manner budgeted was likely impermissible. The President, however, disputed this, stating that she relied on the former CFO’s expertise regarding the allowable uses of HEERF. She stated that for months he had trouble making up his mind on HEERF and offered evolving plans for use of the funds. She stated that she did not know that the budget submitted to the Board proposed to use HEERF funds for an unallowable use, and to her knowledge, neither did her staff. She stated that it was not until in or about April 2022, when the interim CFO started, that she understood that applying HEERF funds to NJCU’s pre-existing scholarship program would not be allowable under federal law. The claim that the President did not know this was an issue until April 2022 appears to conflict with the multiple emails she received stating that this was an issue.

In its response to a draft of this report, NJCU maintains that the weight of the evidence indicates its former staff did not intentionally misallocate the HEERF funds in the 2022 budget but instead made flawed decisions in difficult circumstances based on a lack of clarity on the allowable uses of HEERF funds. The evidence fails to support this assertion. HEERF’s enabling legislation, as well as guidance from the U.S. Department of Education, are clear about what uses are permissible for HEERF funds. NJCU can point to no authority allowing the dramatically different planned use of HEERF funds in the 2022 budget. NJCU’s claim of legitimate confusion regarding HEERF III funds is further undermined by the emails in this matter recognizing the applicable law and by the fact that NJCU administered two prior grants of HEERF funds without issue.

But even if NJCU was right that the guidance was confusing, the senior administrators’ conduct was irresponsible. Preparing a budget that based approximately eight percent of its funding on an open question, and then failing to conclusively resolve the open question over a ten-month period, shows the senior administrators fundamentally failed in their duties to protect NJCU. Even if one accepts that they were confused in June 2021, which does not appear to be the case, the senior administrators’ failure to resolve that confusion and alter course at any point from June 2021 to April 2022 is especially inexcusable.

4. NJCU’s Administrators Failed to Notify the Board that the Planned Use of HEERF Funds Would Have Been Unlawful or Take Corrective Action to Address the Budget Gap it Created

NJCU’s administrators aggravated the situation and undermined the University’s governance by failing to notify the Board of Trustees of an issue that was a substantial threat to the University. Critically, NJCU administrators failed to tell the Board about the risks inherent in the budget prior to its adoption. They also failed to take any corrective action to address the budget gap they had created during the fiscal year. Their failure to act for an extended period of time was the principal cause of NJCU’s financial emergency.

The former CFO stated that as the summer of 2021 progressed following adoption of the budget, it was apparent that the existing scholarship program would not be funded with HEERF grants. He stated that he brought this issue to the President’s attention, but she did not want the administration to amend the budget. He stated that the President instructed him not to tell the Board about potential deficits or discuss HEERF with them because it might “confuse” the Trustees. The former CFO stated the President later told him that she was concerned her contract would not be renewed if the University’s budget showed an operating loss. The former CFO told OSC that the University had begun funding the scholarship program with its cash reserves instead of HEERF funds by the commencement of the fall 2021 semester.

As discussed above, in an internal communication dated December 7, 2021, more than five months after the adoption of the budget, the former CFO again stated to the President that the administration should assume NJCU could not use HEERF III funding for the existing scholarship program. The President responded “I need a call at 9 am today on this. It is not serving [NJCU] well to be making this determination at this late date.” Less than a month after that exchange, however, the President sent the former CFO an email directing him to prepare a new budget estimate that assumed NJCU could use “COVID student money for housing and other scholarships,” suggesting that she ignored the former CFO’s advice and intended to provide an inaccurate financial picture to the Board.

The former CFO stated to OSC that he told the Chair of the Board’s Audit and Finance Committee in August 2021 that the scholarship program was funded with the University’s cash reserves, instead of HEERF funds. According to the former CFO, the Chair of the Committee was persuaded by the President and the Enrollment VP, who represented to him that they would institute a plan to have the student portion payments returned to NJCU by spring 2022. The former CFO left the University in March 2022.

When OSC asked the President if she ever told the Board the scholarship program might be unfunded, she stated that she did in “various conversations” that occurred from the summer of 2021 through the winter of 2022. This is inconsistent, however, with her prior representation that she was unaware of any problems with the scholarships or HEERF funds until the matter was brought to her attention by NJCU’s interim CFO in April 2022. The President also disputed the former CFO’s account that she directed him not to discuss potential deficits or HEERF with the Board. She stated that she instead told the former CFO to simplify his explanation of budget issues so he did not “confuse many of the members who did not have a financial background.”

Trustees interviewed by OSC disputed the claims made by the President and former CFO. According to the Chair of the Board’s Audit and Finance Committee, the Board was unaware of the misallocation of HEERF money or lessened cash reserves until this information was brought to the Board’s attention by the interim CFO in spring 2022. The Chair of the Board gave a similar account, stating that $14 million of HEERF money was budgeted for an improper purpose and the issue was not brought to the Board’s attention until sometime between April and June 2022 when the interim CFO raised the issue. The Chair could not recall ever being notified, prior to the interim CFO’s presentation, that the 2022 budget was based on assumptions about the allowable uses of HEERF money or that the administration was deviating from the approved budget. He further stated that, prior to the notification from the interim CFO, the Board was never advised of the possibility that the scholarships were unfunded and being charged against cash reserves. Though the University had run deficits in prior years, the Chair stated this unexpected $14 million budget gap, combined with low cash reserves, threatened the University’s fiscal well-being and caused the Board to declare a financial emergency. Documentary evidence also suggests that the Board was not apprised of the budgeting issue. A memorandum presented during a November 2021 meeting of the Board’s Audit and Finance Committee stated that NJCU’s scholarship program could be paid for with HEERF grants, indicating that senior administrators were continuing to represent that HEERF funds could be used to pay for the pre-existing scholarship program.

The planned misuse of HEERF funds and the failure to take corrective action compounded NJCU’s existing financial woes. In a presentation delivered in June 2022, the interim CFO alerted the Board of Trustees that the adopted budget’s year-end projection of a roughly $480,000 surplus would likely turn into a $13.8 million deficit, with the University possessing only 25.5 days of operating cash on hand. Additionally, he projected that the University’s deficits would continue into 2023, with a projected end of year deficit of $10.7 million in that year. The administration’s misrepresentation that the HEERF funds could be used to fund the existing scholarship program and its failure to take corrective action caused NJCU to declare a financial emergency and adopt an interim, 90-day budget in place of the typical annual budget adopted in June of each year.

During the interim, 90-day budget, the interim CFO took the lead in developing a budget for the full 2023 fiscal year. This budget, which was developed on a modified cash basis instead of an accrual basis, initially projected a $22.7 million deficit for 2023.[30] Numerous cost savings were identified before final adoption of the budget, further reducing the deficit by $10 million. These measures included employee lay-offs, pay cuts, furloughs, eliminations of vacant positions, reductions to non-personnel budgets, and cuts to academic programs. Despite these efforts, NJCU was still expecting a 2023 year-end deficit of nearly $13 million.

In response to a draft of this report, NJCU asserted that the improper budgeting of HEERF funds was not the cause of NJCU’s financial emergency. NJCU maintains the emergency was instead the product of longstanding financial challenges. Although it is true, as recognized in this report, that NJCU faced substantial and worsening challenges, the lack of transparency to the Board and NJCU’s failure to alter course when it was clear there was a large budget gap plainly led to the financial emergency. The University’s assertion is further contradicted by statements made to OSC by numerous members of NJCU’s Board of Trustees and its current administration.

Former President Henderson, in her response to a draft of this report, stated that she and her staff worked to allocate HEERF funds consistent with evolving guidance. She further stated there were no misrepresentations or concealment of information from NJCU’s Board.

C. NJCU’s Board of Trustees Received Inadequate Training and Exercised Poor Oversight

OSC finds that the NJCU Board of Trustees’ poor oversight of the President and her administration likely contributed to NJCU’s financial decline. Additionally, OSC’s review has determined that NJCU’s Board was inadequately trained, a fact that likely contributed to the lack of effective Board oversight. Even after the financial emergency became apparent, the Board failed to ascertain the cause of the financial emergency, an omission that may have led to the University paying additional, unwarranted compensation to the President through a voluntary resignation process.

1. NJCU’s Board of Trustees Did Not Adequately Oversee President Henderson

New Jersey law vests boards of trustees at public institutions of higher education with broad powers and ultimate responsibility over the institutions they serve. By law, they are “accountable to the public for the fulfillment of the institution’s mission . . . and for effective management of the institution.”[31] This includes the power to hire and fire the president, who explicitly serves “at the pleasure of the board of trustees.”[32]

The President’s employment contract contained provisions on performance evaluations and termination, both with and without cause. The performance evaluation provision required that an annual, written review be conducted by the Board of Trustees and also provided that the Board “may” commission an external review no less than every five years. The grounds for a termination “for cause” were laid out in the contract, and included the following: (1) willful misconduct, gross negligence, or material dishonesty in the performance of her duties hereunder that harms the University; (2) willful and continued failure substantially to perform the duties of the position other than for reason of illness or disability; and (3) breach of fiduciary duty involving personal profit.

OSC requested copies of all performance evaluations of the President and received only one: a written evaluation prepared by an external reviewer in February 2017.[33] OSC requested, but did not receive, any written evaluations prepared by the Board of Trustees.

OSC received conflicting information when it asked the President and members of the Board about performance evaluations, but it is clear that the President did not receive the required annual, written evaluation by the Board. One Trustee who served as Chair of NJCU’s Board of Trustees for approximately 15 years stated that, under his tenure, the Board conducted annual sit-down reviews of the President, though he conceded that they were not memorialized and the Board may have missed a “couple” of years. The President stated she was verbally evaluated each year by the Board Chair.

Both the current Chair and Vice-Chair stated that the Board of Trustees did not conduct any performance evaluations of the President until the current Chair conducted one in late 2021. But even then the evaluation was not memorialized. When asked what impact the lack of evaluations had, the current Chair stated that evaluations are the only way to hold the President accountable and that without them it was difficult to do so. One other current Trustee could not recall if he was involved in evaluating the President’s performance, and a former Trustee, who left the position prior to 2021, stated he could not recall seeing a written review of the President but that her performance was a topic of discussion among Trustees.

Despite the lack of annual, written evaluations, the Board still raised the President’s salary several times. Her original five-year contract salary was $295,000 per year; the Board raised this to $340,000 when it renewed her contract for another five years in 2017. By the date of her resignation, it had been raised again to $360,000.

The Board’s failure to conduct annual, written evaluations deprived the Board of a mechanism for establishing and measuring performance standards for the President. Without that mechanism, the Board was likely unable to hold her fully accountable throughout her tenure.[34]

In addition, several of the Board members stated that, when making requests for information from the President or her administration, they had recurring problems with the speed or sufficiency of the information they were provided. All expressed some degree of concern over the school’s years-long enrollment declines and increasing expenses. Three members—including the Board Chair, Board Vice-Chair, and Chair of the Board’s Audit and Finance Committee—told OSC they requested specific solutions to the school’s challenges but plans were never provided or implemented by the President. In particular, the Chair of the Audit and Finance Committee stated that the President’s administration had weak financial oversight and could not produce accurate, current financial records.

All of these problems and concerns could have been addressed through standards developed and measured in annual performance evaluations. The Board’s failure to do so likely contributed to the continual decline of the University’s financial position.

NJCU also claimed that the current Board of Trustees conducted a memorialized review of the President at the end of 2021. OSC requested such documents early in this investigation, but NJCU only provided documentation it claims supports its assertion with its response to a draft of this report on May 5, 2022. The documents provided by NJCU appear to be self-evaluations produced by the President, not memorialized evaluations conducted by NJCU’s Board.

Former President Henderson provided additional self-evaluations to OSC on May 15, 2023 in response to a draft of this report. None of these documents is an evaluation conducted by NJCU’s Board. She also stated she believes she did have oversight by and transparency with NJCU’s Board.

2. The Board of Trustees Failed to Ascertain the Causes of the Financial Emergency and May Have Deprived Itself of Possible Remedies

The President’s contract would have expired on December 31, 2022. That contract stated that she could be terminated for cause for several performance-based reasons, including (1) willful misconduct, gross negligence, or material dishonesty in the performance of her duties; (2) willful and continued failure to substantially perform the duties of her position; and (3) breach of fiduciary duty involving personal profit.

On June 23, 2022—four days before the declaration of financial emergency—the President signed a voluntary separation agreement with the University. This voluntary termination of employment entitled her to several contractual benefits, including a 12-month “transitional sabbatical” at 80 percent of her base pay, or $288,000. The University also purchased the vehicle it was leasing for her benefit and transferred ownership of the vehicle to her. Lastly, the University continued to provide the President a housing stipend. In response to a draft of this report, NJCU reported that former President Henderson received $7,500 under this stipend.

Based on the facts established through this investigation, including the President’s failure to notify the Board of a significant financial problem and her failure to take timely corrective action to address it, NJCU may have had multiple causes for termination under the President’s employment contract. The Board Chair acknowledged to OSC that the Board could possibly have terminated the President for cause, but stated he was concerned doing so might lead to a protracted dispute.

The Board failed to properly ascertain the causes of the financial crisis. When asked whether the Board took any steps to determine how or why the misallocation occurred, the Chair stated he believed it was important for the Board to “move forward.” He stated that with the responsible parties gone, the Board did not hold any discussions about allocating blame. The Board’s failure to ascertain the causes of the financial crisis may have prevented the Board from ensuring accountability and terminating the President for cause. Ultimately, this may have led to the President receiving lucrative voluntary separation benefits despite evidence suggesting she withheld material financial information from the Board of Trustees at a time when the University was in financial distress.

NJCU, in its response to a draft of this report, stated that its Board acted reasonably in ending the President’s employment by way of voluntary separation. NJCU asserted this was the most cost-effective way to proceed and did not subject the University to potential additional costs. This assertion is not responsive to OSC’s finding. To be clear, OSC is not asserting that NJCU’s Board should have terminated the President for cause. Instead, OSC finds the Board deprived itself of the opportunity to explore potential remedies because it did not take steps to ascertain the causes of the financial emergency.

In her response to a draft of this report, former President Henderson asserted the report incorrectly implies she could have been terminated for cause, when no legitimate basis existed for that action. OSC takes no position on whether the President should have been terminated. Rather, as explained above, OSC finds the Board failed to ascertain the cause of the financial emergency and deprived the University of the opportunity to act based upon that information.

3. NJCU’s Trustees Were Not Properly Trained for their Roles on the Board

Improper training of NJCU’s Board of Trustees appears to have played a role in their inadequate oversight of the President and her administration. In 2009, the Legislature required public institutions of higher education to provide “training to each of its governing board members on the legal and ethical responsibilities of a member of the governing board.”[35] This requirement reflects the important role board members play in governing and overseeing public colleges and universities. Their role is particularly important in New Jersey’s public colleges and universities because of the minimal state involvement in governance.

Several Trustees stated they received no formal training upon joining the Board. One stated that he was provided only conflict of interest information through an automated state training program and had to request a copy of the Board’s bylaws, while another could not recall whether he was provided any materials at all. The current interim President stated that Trustee training involves providing the Trustees with a handbook in addition to performing state-mandated ethics training.[36] This handbook contains the NJCU trustees’ oath, the Board’s bylaws, committee charters, a list of members and meeting dates, a reference guide prepared by the New Jersey Association of State Colleges and Universities, the State’s Uniform Ethics Code with a blank conflict of interest form, and further information about NJCU.

By way of contrast, representatives from other public institutions of higher education in New Jersey told OSC that members of their boards are provided with orientation training, either developed in-house or provided by a national organization focused on the strategic roles that boards of trustees serve within their institutions. Several reported that this training involved presentations on their institution’s structures and the responsibilities of board members. One institution provided an annual refresher training that is generally attended by all members of their institution’s board.

OSC finds that NJCU did not comply with the training requirement imposed in 2009 because it does not have a training program. The University’s Trustee onboarding process was also insufficient to prepare NJCU’s Trustees for their role and responsibilities. The absence of a training program and the insufficient onboarding process contributed to inadequate oversight over University operations.

In 2021, the Legislature imposed an additional requirement on the training public institutions of higher education are obligated to provide to board members. Effective April 2022, those institutions must consult with OSHE when developing the training.[37] The Legislature also stated in the 2021 law that the training must be “designed to clarify the roles and duties of a governing board member.” [38]

In its response, NJCU reported that it is currently consulting with OSHE to enhance its board training program.

D. A Combination of Declining Enrollment Trends and New Jersey’s Decentralized Higher Education System May Lead to Further Financial Issues at NJCU and Other Public Institutions of Higher Education

New Jersey’s decentralized system of higher education provides public colleges and universities with broad authority to manage and administer their operations with minimal oversight by the State. The State’s higher education system permits public colleges and universities to, among other things, unilaterally set tuition rates, increase spending on programs, expand real estate portfolios, construct facilities and buildings, incur debt, and hire executive-level employees such as the president. Public colleges and universities also set their own strategic goals, develop their own budgets, and manage their own finances. They exercise this autonomy while receiving a significant amount of public funds from the state and federal governments.

Currently, the state system provides few checks and balances to ensure that state funding is spent prudently. As noted above, while the institutions must submit annual audit reports to OSHE each year, OSHE lacks authority to recommend or direct any corrective action if issues are noted. OSHE does not have the authority to intervene in public institutions to prevent a financial crisis or avoid imprudent budgeting or spending. This creates risks that are inherent in the decentralized system the State has established.

Another effect of the decentralized decision-making is that New Jersey’s public colleges and universities are more likely to compete with each other to attract students from the same shrinking pool. Declining enrollment trends nationwide, and in New Jersey, will likely intensify competition among the State’s public institutions of higher education and lead institutions to implement potentially expensive efforts to attract students. In the absence of more intensive coordination by the State during a period of contraction by colleges and universities, New Jersey colleges and universities may respond with progressively risky ventures that increase financial expenses without improving enrollment figures, thereby weakening an institution’s financial position. The decentralized nature of the New Jersey’s higher education system increases risks during a period of contraction and increased competition.

Recommendations

OSC recommends that NJCU:

1. Establish and implement robust policies, procedures, and internal controls related to budgeting and the accountability of the administration to the Board of Trustees. These documents should require, among other things, the disclosure of assumptions and risks during the budgeting process and formalize the role of the CFO in reporting to the Board. Those newly established policies, procedures, and internal controls should be publicly posted to the University’s website to ensure appropriate transparency and accountability.

2. Conduct a comprehensive review of the current composition of the Board of Trustees and its operational policies and procedures. Effective governance of an institution of higher education requires a board of trustees that consists of individuals with the expertise necessary to meet the institution’s needs. To ensure that it is equipped to provide effective governance of the University, NJCU’s Board of Trustees should commission an independent external review to determine whether the University would benefit from adjustments to the Board, such as the addition of new board members or the creation of additional committees. That review should also include an evaluation of current board operations to ensure there are appropriate accountability measures in place.

3. Review training practices and institute a formal training program for board members. Members of NJCU’s Board of Trustees should promptly undergo comprehensive training involving the governance of public institutions of higher education and be required to complete refresher training on this topic at regular intervals, ideally annually.

4. NJCU’s Board of Trustees should conduct and document, in writing, annual performance evaluations of its President, whether required by contract or not. Such performance evaluations should include measurable performance standards against which the President’s performance can be evaluated.

5. Engage, for an appropriate time period, an independent financial monitor with expertise in overseeing the finances of a public institution of higher education to ensure the administration and Board are discharging their duties in accordance with established policies, procedures, and internal controls and with the highest standards of integrity and transparency. That individual should report directly to the Chair of the Audit and Finance Committee.

6. NJCU would benefit from establishing a program that assesses its academic offerings to ensure the financial sustainability of the University. Such a program would inform whether NJCU is offering the programs and degrees necessary to encourage interest in the University, properly allocating resources, and adjusting to shifting market demands. Accordingly, OSC recommends that NJCU adopt a program that regularly reviews its academic program portfolio.

OSC recommends that the Legislature:

1. Evaluate whether OSHE’s existing powers adequately guard against poor decisions made by the administrations or boards of public colleges and universities and whether existing reporting and other requirements adequately protect the interests of taxpayers and students of public colleges and universities as well as the institutions themselves. Address risks through the adoption of legislation.

2. Authorize and direct OSHE through legislation to institute requirements related to reporting by CFOs to boards of trustees, audit committees, and OSHE, including with regard to the validity of the preparation of budgets, accuracy of financial reports, and duties to protect public funds.

Footnotes

[1] The average undergraduate student population among New Jersey’s 13 public four-year institutions in fall 2021 was approximately 11,000. The smallest was Rutgers Camden, with 4,856. The largest, Rutgers New Brunswick, had 36,152.

[2] The remaining 8 percent is classified as “missing/other.”