A Review of New Jersey’s Lifeguard Pension Law and Municipal Programs

- Posted on - 07/23/2025

Table of Contents

- Executive Summary

- History of the Lifeguard Pension Program

- Scope of Review

- Review Findings and Conclusion

Executive Summary

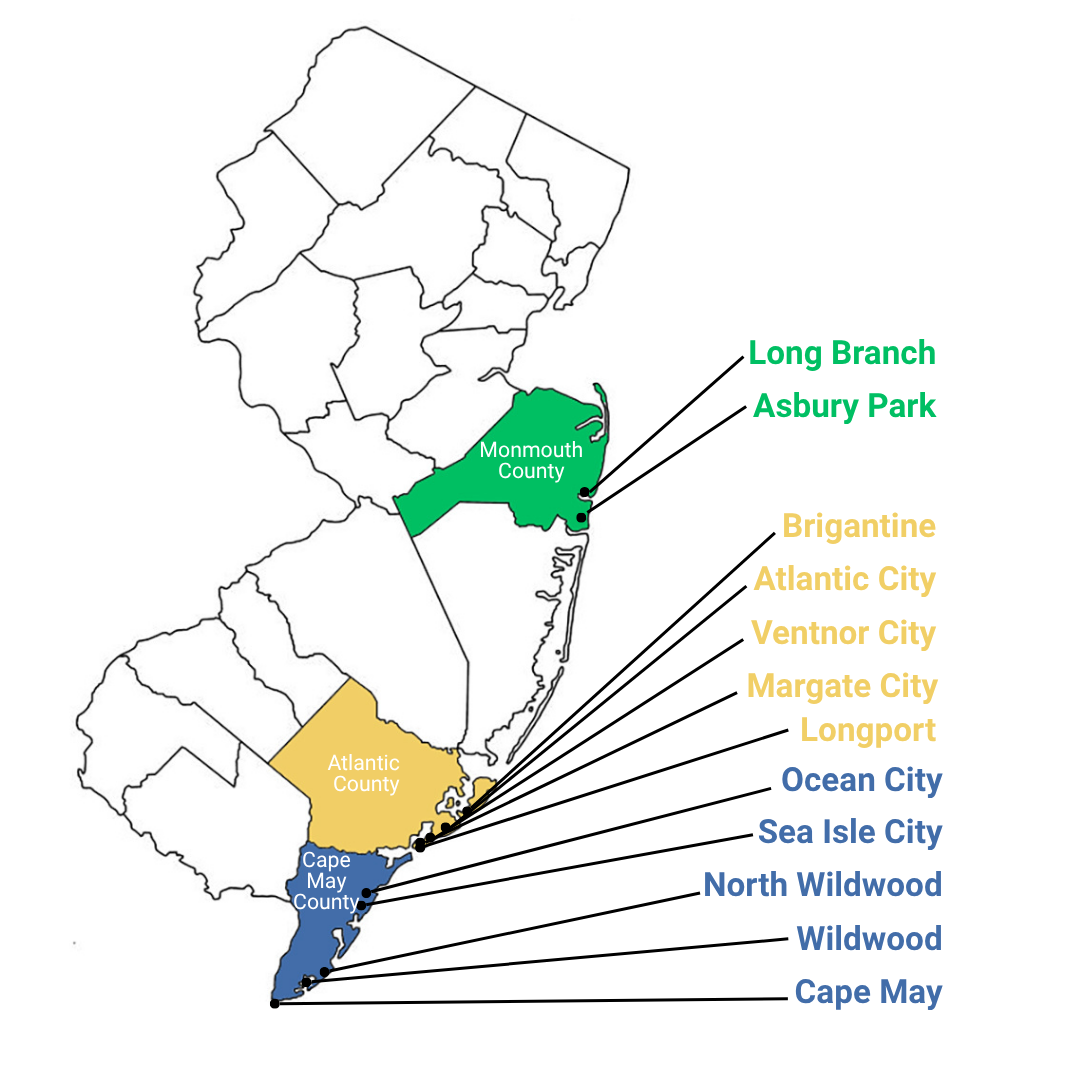

The Audit Division of the Office of the State Comptroller (OSC) has issued reports based on performance audits of nine municipalities in Atlantic, Cape May, and Monmouth counties identified as having a lifeguard pension program in accordance with N.J.S.A. 43:13-23 to -29 (“Lifeguard Pension Law”). Additionally, we sent letters to two other municipalities that are legally required to have lifeguard pension programs but currently do not, informing them of their obligations under the Lifeguard Pension Law. As a result of this work, we have questioned the ongoing value of state law mandating that pensions be provided by a small number of municipalities with beaches to a small fraction of the lifeguards hired by the municipalities. This report shares the findings from our review of the Lifeguard Pension Law and recommends that the Legislature make changes.

Specifically, our review of the law and our audits of the cities’ programs adopted in compliance with the law found:

- The benefits required in the Lifeguard Pension Law are overly generous as compared to state-administered pension programs that do not provide benefits to seasonal employees.

- Beach municipalities organized as townships, boroughs, and villages are not required by statute to provide lifeguard employees with similar benefits, leading to inconsistent treatment of municipalities and lifeguards.

- Most of the people receiving lifeguard pensions are also enrolled in other pension programs. Of the 206 lifeguard retirees receiving pensions in 2022, 104 also participate in a state-administered pension program, such as Public Employees' Retirement System (PERS), Teachers' Pension and Annuity Fund (TPAF), or Police and Firemen's Retirement System (PFRS). This is inconsistent with overarching state policy on pensions, which has made it difficult to obtain double pensions by limiting the simultaneous accrual of annual pension credits in state-administered pensions programs.

- Lifeguard pension programs making payments to retirees cost municipalities approximately $1.8 million per year, or an average of about $9,100 per retiree.

- The total liability for lifeguard pensions for six municipalities – Atlantic City, Brigantine, Longport Borough, Margate City, Sea Isle City, and Ventnor City – is $37 million, according to actuarial estimates. Of that amount, $34.2 million is unfunded in the pension funds maintained by those municipalities, which means today’s and tomorrow’s taxpayers will be responsible for funding pension obligations that have accrued over past decades. The remaining six municipalities likely face liabilities in the millions, if not tens of millions.

- The Lifeguard Pension Law does not specify whether cities are required to return employees' pension contributions, which amount to four percent of their pay, at any time. As a result, all but one city keeps all of the funds contributed by lifeguards, most of whom never get close to the required years of service to receive a pension. This effectively taxes the labor of more junior lifeguards to pay for retiree benefits. This is inconsistent with state law establishing other pension programs, which allow funds contributed by public employees to be returned to them when they stop accruing eligible time toward their pension.

These findings suggest that the law is outdated and inequitable, imposing excessive financial burdens on a few municipalities and certain lifeguards while offering disproportionately generous benefits to other lifeguards, and overall serving as an outlier compared to state pension policies.[1] In view of the findings in this report and the nine audit reports OSC released simultaneously with this report, we recommend that the Legislature reform this system by:

1. Amending the Lifeguard Pension Law to prospectively eliminate the requirement for fourth-class cities to provide lifeguard pensions, aligning them going forward with all other municipalities with beaches in New Jersey. The amendments should allow for a phased closure of the program that requires cities to fulfill their legal obligations and negotiate as necessary with existing retirees and others who have a vested interest in a lifeguard pension.

2. Requiring prospectively the return of employee contributions to employees who do not meet the minimum retirement requirements under the Lifeguard Pension Law to ensure fairness and to align the program with state-administered retirement programs that authorize the return of employee contributions.

History of the Lifeguard Pension Program

In 1882, the Legislature created a system of classification of New Jersey cities.[2] The classification system, which is currently codified as N.J.S.A. 40A:6-4, established four classes of cities. The first three classes divide cities by population. The fourth class includes cities that border the Atlantic Ocean. Under this system, there are currently 11 fourth-class cities in New Jersey.

Figure 1: Municipalities with Lifeguard Pension Obligations

In 1928, the Legislature adopted a law that required fourth-class cities to provide a pension upon retirement for lifeguard officers and lifeguards.[3] The law was amended in 1929 to provide pension benefits to surviving spouses and minor children.[4] In 1936, the law was amended again to increase the retirement age, the required years of service, and the amount of employee contributions.[5] The Lifeguard Pension Law also mandates that fourth-class cities establish a pension fund, with contributions from both the city and the lifeguard, and appoint a commission to manage the fund and administer the pension program. The statutes empower the pension commission to make all necessary rules and regulations. For nearly a century, this law has remained unchanged.

The table below summarizes the lifeguard pension program funding, eligibility criteria, retiree compensation, and pension commission requirements established by the Lifeguard Pension Law.

Figure 2: Lifeguard Pension Law Requirements

|

Topic |

Program Provisions |

|

Plan Funding |

|

|

Employee Contribution *; ^ |

4% of salaries |

|

Employee Withdrawal of Contributions ^^ |

Laws neither authorize nor prohibit withdrawal of employee contributions |

|

Employer Contribution *; ^ |

4% of lifeguard salaries plus related fines, penalties, and donations |

|

Unfunded Pension Liabilities *; ^ |

Met through taxation |

|

Retiree Eligibility Criteria |

|

|

Years of Service †; ° |

20 years, with continuous service for a period of 10 years preceding retirement application |

|

Year of Service Defined ‡; ** |

Part of the calendar year as the lifeguard force is normally employed |

|

Minimum Age †; ° |

45 years of age |

|

Disability Benefit §; † |

Yes, receive half pay |

|

Surviving Spouse and Children Benefit ‡; ‡‡ |

Yes, with restrictions |

|

Retiree Compensation |

|

|

Retiree Compensation †; ° |

Half pay |

|

Year’s Salary Defined ‡; ** |

Salary a lifeguard receives during normal employment in any calendar year |

|

Pension Commission |

|

|

Number of Commissioners ‖; §§ |

Four |

|

How a Commissioner Is Appointed ‖; §§ |

By Mayor or Chief Executive Officer, with the advice and consent of the governing body |

|

Commission Members ‖; §§ |

One senior lifeguard, one standard lifeguard, and two non-lifeguard residents |

|

Who Manages and Controls the Fund ‡; °° |

Pension Commission |

|

|

|

|

Current Statutes: ^ N.J.S.A. 43:13-27; ° N.J.S.A. 43:13-24; **N.J.S.A. 43:13-23; †† N.J.S.A. 43:13-25; ‡‡ N.J.S.A. 43:13-26; §§ N.J.S.A. 43:13-28; °° N.J.S.A. 43:13-29 |

|

|

Legislation: * L. 1928, c. 272 as amended by L 1936, c. 108; † L. 1928, c. 272 as amended by L 1929, c. 59 and L. 1936, c. 108; ‡ L. 1928, c. 272 as amended by L. 1929, c. 59; § L. 1928, c. 272, ‖L. 1928, c. 272 |

|

|

^^ No Statutes or Legislation Applicable |

|

With the exception of Atlantic City, New Jersey’s fourth-class cities largely ignored the requirements of the Lifeguard Pension Law until the 1980s. In 1984, Ventnor City argued before the New Jersey Superior Court that the establishment of a pension program was optional and not obligatory. The court held that the intent of the legislation was to require the creation of a pension program for lifeguards employed by fourth-class cities and that the use of the word “may” in N.J.S.A. 43:13-24 did not mean the law was optional, but rather indicated that lifeguards could, but were not required to, retire at age 45.[6] By the mid-1990s, eight additional fourth-class cities established pension programs for their lifeguard employees. In 1999, a court again rejected an argument regarding the use of the word “may” in the statute. The court noted that the Legislature had acquiesced to the earlier interpretation of the law as requiring the payment of pensions to qualifying lifeguards and had not amended the statute.[7]

Between 2001 and 2008, members of the Senate and Assembly introduced bills that would amend the Lifeguard Pension Law. The bills sought to remove the requirement for continuous service prior to retirement, standardize the calculation of retirement benefits, allow for the return of employee contributions plus interest, and require that the State pay for any increased costs resulting from the amendments.

In 2013, Ocean City unanimously passed a resolution requesting that the State consider eliminating the requirements of the Lifeguard Pension Law. The resolution cited the effect on the municipal budget and noted that the Legislature in other contexts had ended the practice of part-time and/or seasonal employees being members of pension systems.

In spring 2016, members of both the Senate and Assembly introduced bills that would allow municipalities with a lifeguard pension fund established through the Lifeguard Pension Law to eliminate eligibility for a pension prospectively.[8] These bills never cleared committee and were not voted on by either house.

In March 2024, lifeguards from the Borough of Avalon sued the Borough, seeking a declaration that Avalon is a city of the fourth class for the purposes of N.J.S.A. 43:13-24 to - 26.[9] Avalon argued that the Lifeguard Pension Law does not apply because it is not a city. The lifeguards’ argument, if accepted, would have expanded the applicability of the pension statute to every New Jersey municipality along the Atlantic Ocean employing lifeguards. In September 2024, the court dismissed the lifeguards’ complaint.

Scope of Review

We identified 11 fourth-class cities required to have a lifeguard pension program pursuant to the Lifeguard Pension Law. We also learned that Longport Borough established a pension program in 1987 even though it is not considered a fourth-class city. The cities of Asbury Park and Long Branch reported that they do not have operating lifeguard pension programs. We sent letters to both cities regarding the application of the Lifeguard Pension Law. Both cities provided detailed responses to our letters, contending that that the law is outdated and possibly unconstitutional. Asbury Park and Long Branch contend that the law unfairly imposes costs on certain municipalities without a rational basis for the unequal treatment of municipalities in similar circumstances.

The table below lists the 12 municipalities that have or are required to have a local pension program for lifeguards.

Figure 3: Municipal Lifeguard Pension Programs at a Glance for 2022

|

Municipality |

Number of Retirees |

Active Employees |

Payments to Retirees |

Employer Contribution |

Funds Reserved for Future Benefits |

|

Asbury Park |

Reported No Lifeguard Pension Plan |

||||

|

Atlantic City |

89 |

153 |

$1,098,200 |

$1,026,000 |

- |

|

Brigantine |

12 |

106 |

$81,800 |

$60,000 |

$562,000 |

|

Cape May |

11 |

88 |

$79,900 |

$40,000 |

$652,000 |

|

Long Branch |

Reported No Lifeguard Pension Plan |

||||

|

Longport Borough |

11 |

67 |

$76,200 |

$22,400 |

$333,400 |

|

Margate City |

10 |

70 |

$74,600 |

$118,800 |

$740,300 |

|

North Wildwood |

11 |

97 |

$48,500 |

$27,500 |

$ 171,400 |

|

Ocean City |

46 |

163 |

$300,300 |

$240,000 |

$28,700 |

|

Sea Isle City |

2 |

100 |

$9,400 |

$10,000 |

$1,058,100 |

|

Ventnor City |

9 |

75 |

$58,400 |

- |

$149,100 |

|

Wildwood |

5 |

95 |

$39,700 |

$ 231,200 |

$658,000 |

|

Statewide Total |

206 |

1,014 |

$1,867,000 |

$1,775,900 |

$4,353,000 |

|

Data for the year ending December 31, 2022 |

|||||

We identified ten municipalities with operating lifeguard pension programs. We included data from Brigantine in this report but excluded it from the scope of work performed. We issued a performance audit of Brigantine and its lifeguard pension program in December 2022.[10] We reviewed the remaining nine operating lifeguard pension programs for the period 2020 through 2022. The purpose of this review was to determine whether the Lifeguard Pension Program provided benefits consistent with other state-administered pension programs and to examine the costs and liabilities involved with lifeguard pensions. The individual audit reports of the nine municipalities, which can be found on the OSC website, are summarized and in full in Appendix A of this report.

Review Findings and Conclusion

Findings

Seasonal employees are ineligible for participation in state-administered pension programs. In contrast, the Lifeguard Pension Law provides an overly generous employee benefit to seasonal employees that is inconsistent with the benefits provided by other retirement programs operated by the State, such as Public Employees' Retirement System (PERS).

Of the 206 lifeguard retirees receiving pensions in 2022, 104 also participated in another state-administered pension program such as PERS, Teachers' Pension and Annuity Fund (TPAF), or Police and Firemen's Retirement System (PFRS).

The Lifeguard Pension Law does not require cities to return employee contributions.

The employee benefits required by the Lifeguard Pension Law add significant additional costs to the municipalities that offer a pension program for lifeguards compared to similar municipalities organized as townships, boroughs, or villages.

Basis for Comparison

The State established PERS after the repeal of the law creating the former State Employees’ Retirement System.[11] PERS covers substantially all full-time employees working in local and state employment who are not required to be members of another state-administered retirement system.[12] Unlike police officers, firefighters, and teachers, no pension system at the state level requires the enrollment of lifeguards. Therefore, a lifeguard meeting all other pension eligibility criteria would enroll in PERS. The Legislature enacted significant changes to the laws establishing PERS between 2007 and 2011.[13] The amendments created five tiers of membership for PERS based on the date the employee became eligible for pension enrollment. In 2010 and 2011, the Legislature enacted changes[14] to pension and health care benefits for public employees. The legislation gradually increased pension contributions for all PERS employees to 7.5 percent of an employee’s base pay. Additionally, for local government employees hired after June 28, 2011, the amendments required employees to work at least 32 hours per week, increased the retirement age for most PERS employees to 65, and reduced the pension benefit for each year of service. These reforms affect the fifth tier of PERS membership. Tier 5 members include employees eligible for enrollment on or after June 28, 2011. Benefits for non-veteran, Tier 5 PERS members are an appropriate basis for comparison to the benefits required by the Lifeguard Pension Law.

Seasonal Employee Benefits Excluded from PERS

Under state law, seasonal employees, including lifeguards, are ineligible to join PERS and other state-administered pension programs. Seasonal employment is defined as occasionally working in a position that does not lead to permanent employment and does not extend beyond six consecutive months for employing locations that report on a twelve-month basis, or five months for employing locations that report on a ten-month basis. The Lifeguard Pension Law requires fourth-class cities to provide retirement benefits to seasonal employees who typically work between June and September. The Lifeguard Pension Law provides benefits for lifeguards that far exceed other seasonal employees who are ineligible for state-administered pension programs. We continue our comparison of the pension programs below despite this notable difference to highlight other inconsistencies in the design of the pension programs.

Benefit Comparison

We reviewed statutory benefits available to newly hired, non-veteran PERS Tier 5 members and newly hired lifeguard employees in fourth-class cities. The table below identifies the more significant differences between the state-administered PERS program for Tier 5 members without veteran status and the state-mandated system under the Lifeguard Pension Law.

Figure 4: Comparing Benefits and Eligibility of NJ's Lifeguard Pension and PERS

|

|

Lifeguard Pension Program |

PERS Tier 5 Membership |

|

Plan Funding |

|

|

|

Employee Contribution |

4% of Total Salary |

7.5% of Base Salary |

|

Extra Compensation Pensionable |

✅ Yes |

❌ No |

|

Authorizes the Return of Employee Contributions |

❌ No |

✅ Yes |

|

Retiree Eligibility Criteria |

|

|

|

Minimum Years of Service |

20 Total Years of Service with 10 Continuous Years of Service Prior to Retirement |

Age 65 or Older ➡️ No Minimum |

|

Minimum Age for Full Benefits |

Age: 45 |

Non-Veterans: Age 65 Veterans: Age 55 |

|

Provides Disability Benefit |

✅ Yes |

✅ Yes |

|

Benefits provided to dependents upon death |

✅ Yes, |

✅ Yes, |

|

Program Benefits |

|

|

|

Retiree Compensation |

Half Pay

|

Years of Service Divided by 60 and Multiplied by the Average of Employee’s Highest 5 Years’ Salary |

|

Benefits for Additional Years of Service |

❌ No |

✅ Yes |

|

Restrictions on post-retirement employment |

❌ No |

✅ Yes |

Retirement Age and Employee Contributions

As identified in the table above, PERS eligibility requirements and benefits for typical Tier 5 members differ in significant ways from the programs created by the Lifeguard Pension Law. Pension programs for lifeguards require a smaller employee contribution rate of four percent and a much lower retirement age of 45 compared to PERS, which requires a seven and a half percent contribution and permits retirement at 65. To illustrate the differences, a 25 year-old lifeguard who works for 20 years earning $20,000 each year would contribute $16,000 into the pension fund during their career.[15] That employee could retire at 45 and receive annual payments of $10,000 for the rest of their lives. If the employee lives to age 80, they would receive $350,000 in total payments. In contrast, a 25 year-old PERS Tier 5 employee earning $20,000 each year would contribute $60,000 into the pension fund while working until the PERS retirement age of 65. The PERS employee could retire at age 65 and receive annual payments of approximately $13,300 after 40 years of service. If the employee lives to age 80, they would receive total payments of $200,000. Under this hypothetical scenario, seasonal lifeguards contribute less to the pension fund, may retire earlier, and receive significantly more in lifetime benefits compared to their PERS counterparts.

Figure 5: A Retired Lifeguard Would Receive About $150,000 More in Lifetime Payments than a Retired State Employee

Pension-Eligible Compensation

State-administered pension programs like PERS exclude extra compensation such as overtime, stipends, or bonuses from pension eligible salary. The Lifeguard Pension Law does not similarly exclude extra compensation and thus is vulnerable to abuse. Six of the ten operating lifeguard pension programs use total employee compensation reported on an employee’s annual IRS Form W-2, which would include overtime and other forms of additional pay, to calculate retiree benefits. As of December 31, 2022, the 206 retired lifeguards received payments averaging approximately $9,100 per year. In 2022, the highest individual retirement benefit paid that year was approximately $60,900 while the lowest was around $500.

Return of Employee Contributions

The Lifeguard Pension Law requires active lifeguards to contribute four percent of their compensation to the program but does not require fourth-class cities to return pension contributions to employees. Our review found that only North Wildwood permitted the return of employee contributions. Employee contributions remain with each fourth-class city to fund retiree benefit payments. To illustrate, an employee with average annual earnings of $15,000 would contribute $600, on average, for each year of service. If this employee left employment after 10 years, their accumulated contributions of $6,000 would remain with their employer unless they worked in North Wildwood. This program design is contrary to the design of the three largest state-administered plans, including PERS. PERS allows employees to withdraw their contributions with interest after terminating employment. The failure of the law, and all but one of the programs created under it, to require the return of employee contributions effectively creates a wage tax for many lifeguards to provide benefits to relatively few retirees.

Duplication of Benefits

Our review revealed that 104 of 206 retired lifeguards—slightly more than half— are receiving pension benefits from the lifeguard pension program while also enrolled as active employees in or receiving benefits as retirees from New Jersey-administered[16] pension programs. Four of five lifeguards who are double-enrolled in pension systems appear to be teachers or otherwise employed in New Jersey schools, which is made possible by the ten-month school year. We identified three lifeguard pensioners who are also enrolled in two state-administered pension systems.

Figure 6: More Than 50 Percent of Retired Lifeguards Have a Second State Pension

In 2015, the New Jersey Pension and Health Benefits Study Commission highlighted the practice of “double-dipping” – employees who obtain one or more public positions and draw pensions or benefits from each of those positions. The report noted that while reforms have limited the practice, “double-dippers have become the ‘face’ of a dysfunctional public pension system.”[17]

Double-dipping is discouraged but not prohibited by state law. The Legislature enacted reforms involving pensions in 2010 that eliminated an employee’s ability to earn pension credit for multiple positions within one state-administered pension system at the same time. The Legislature also placed limits on post-retirement employment for employees receiving pension payments to reduce the burden on taxpayers and decrease the frequency of double-dipping.[18] At the time those changes were enacted, the Legislature did not amend the Lifeguard Pension Law. Thus, under current law, lifeguards may be double- or triple-enrolled in pension systems and in a given year earn pension credit in more than one pension system, thus boosting their retirement income.

Effect of the Lifeguard Pension Law on Participating Municipalities

The pension program for lifeguards required by the Lifeguard Pension Law differs from the benefits offered to other seasonal employees. The benefits provided by the law have not been amended to be consistent with current pension laws for local and state government employees. The laws have significant effect on the current and future finances of the municipalities with an operating lifeguard pension program.

We summarized reported expenditures for each fourth-class city and the Borough of Longport from 2018 through 2022. The reported payments for retiree benefits averaged $1.8 million annually and totaled approximately $9.1 million during the five-year period. The table below details payments by the municipalities required to have lifeguard pension programs.

Figure 7: Lifeguard Pension Program Expenditures 2018 to 2022

|

Municipality |

2022 Lifeguard Retirees |

Retiree Payments |

Average Annual Payment |

|

Asbury Park |

Reported No Lifeguard Pension Program |

||

|

Atlantic City |

89 |

$5,668,000 |

$1,134,000 |

|

Brigantine |

12 |

$340,000 |

$68,000 |

|

Cape May |

11 |

$316,000 |

$63,000 |

|

Long Branch |

Reported No Lifeguard Pension Program |

||

|

Longport Borough |

11 |

$289,000 |

$58,000 |

|

Margate City |

10 |

$328,000 |

$66,000 |

|

North Wildwood |

11 |

$287,000 |

$57,000 |

|

Ocean City |

46 |

$1,401,000 |

$280,000 |

|

Sea Isle City |

2 |

$47,000 |

$9,000 |

|

Ventnor City |

9 |

$280,000 |

$56,000 |

|

Wildwood |

5 |

$174,000 |

$35,000 |

|

Totals |

206 |

$9,130,000 |

$1,826,000 |

Actuarial Estimates of Future Program Costs

Municipalities are required to report financial activity and year-end balances for lifeguard pension programs in their annual audit report. N.J.A.C. 5:30-6.1 establishes the guidelines for municipal audit reports and requires local governments to comply with Governmental Accounting Standards Board (GASB) in making disclosures in the notes to the financial statements. GASB issued Statement 73 to improve the usefulness of information about pensions included in financial reports of state and local governments.[19] GASB Statement 73 requires the use of an actuary to calculate the employer’s total pension program liability and the disclosure of that liability and any offsetting reserves.

Our review found that only Brigantine, Margate City, Longport, Ventnor City, and Sea Isle City obtained the required actuarial reports related to their lifeguard pension program prior to the end of our fieldwork. The remaining five municipalities with lifeguard pension programs failed to obtain actuary reports. The overall failure to obtain actuarial calculations of pension liabilities and make the required financial disclosures prevents local taxpayers and policymakers from learning what the lifeguard pension program costs and ensuring it is funded responsibly.

We engaged the services of an actuary to calculate the liability of three municipalities to provide an estimate of the financial effect of their lifeguard pension programs. These calculations included assumptions regarding salary increases, inflation, and life expectancy, all of which are subject to significant judgment. The calculations relied on the data obtained as part of this project. We made reasonable assumptions when requested information was not provided. Actuarial calculations of total pension program liabilities can change materially based upon changes in assumptions used to calculate the pension liability and the availability of additional data. The table below shows the actuarial estimates of pension liabilities and reserves for six municipalities with lifeguard pension programs.

Figure 8: Accumulated Liability and Reserves

The estimated future cost for lifeguard pensions in the six municipalities above is approximately $37 million. The municipalities have reserved approximately $2.8 million for payments to future retirees. This leaves approximately $34.2 million that must come from future employees or municipal budgets. We did not estimate the costs of the lifeguard pension program in the remaining municipalities. The failure to obtain actuarial calculations and make required financial reporting disclosures prevents the public from understanding the true cost of this program.

Conclusion

The Lifeguard Pension Law requires the creation of a costly long-term benefit program that fails many of its stakeholders. The Lifeguard Pension Law, passed nearly a century ago and last amended in 1936, requires retirement benefits for seasonal employees in only 11 coastal cities.

During our reviews, two lifeguard officers shared their view that the lifeguard pension program provides an incentive for experienced lifeguards to seek continued employment as lifeguards. We have no reason to doubt that lifeguard pensions incentivize longer service, but only 11 of the approximately 40 municipalities that hire beach lifeguards are required to have such a program, and it does not appear that requiring lifelong pension payments is a cost efficient or the only way of incentivizing longevity of service.

The State’s ongoing interest in mandating that this unusual program continue is not evident. The retirement benefits provided to fourth-class city lifeguards far exceed those offered to similar employees working for the State or the other municipal governments along the Atlantic Ocean. The benefits are inconsistent with retirement benefits for seasonal employees in state-administered pension programs who are ineligible for pension program enrollment. In addition, the Lifeguard Pension Law demands contributions from lifeguard employees but does not mandate municipalities to refund these contributions if the employees do not qualify for retirement benefits. Due to the statutory nature of the lifeguard pension program, common sense reforms require legislative action to correct almost a century of the arbitrary and uneven treatment of fourth-class cities, their employees, and their taxpayers.

[1] An examination of municipal pension statutes covering first-class city employees (N.J.S.A. 43:13-1.1 to 22.75), water department employees (N.J.S.A. 43:13-30 to -37), employees in towns (N.J.S.A. 43:13-37.1 to 37.18), and village employees in first-class counties (N.J.S.A. 43:13-38 to -54) for potential reforms may also be warranted but is outside the scope of this review.

[2] L. 1882, c. 46.

[3] P. L. 1928, c. 272.

[4] P. L. 1929, c. 59.

[5] P. L. 1936, c. 108.

[6] Paludi v. Ventnor City, 194 N.J. Super. 565 (Law Div. 1984).

[7] City of Cape May v. Colosi, 325 N.J. Super. 288 (App. Div. 1999).

[8] S. 2085, (N.J. 2016), https://pub.njleg.state.nj.us/Bills/2016/S2500/2085_I1.PDF: A. 3727, (N.J. 2016), https://pub.njleg.state.nj.us/Bills/2016/A4000/3727_I1.PDF.

[9]Wolf v. Borough of Avalon, Docket No. CPM-L-000113-24.

[10] State of N.J. Office of the State Comptroller, Audit Report: A Performance Audit of Employee Benefits: City of Brigantine (Dec. 2022), https://www.nj.gov/comptroller/news/docs/brigantine_audit_report.pdf.

[11] L. 1954, c. 84.

[12] Enrollment in specific state-administered pension systems is required for employees working in certain capacities in government. For example, police officers meeting all other eligibility criteria are required to enroll in PFRS, and certified teachers meeting all other eligibility criteria are required to enroll in TPAF.

[13] L. 2007, c. 92 and 103, L. 2008, c. 89, L. 2010, c. 1 and 3, L. 2011, c.78.

[14] L. 2010, c. 1 & 3, L. 2011, c. 78.

[15] Our example makes a number of assumptions regarding the hypothetical employee’s lifespan, veteran status, retirement type, retirement age, salary, and years of service. The calculations exclude interest earnings on employee contributions held by the employer.

[16] Pensions received from federal government sources or other states were not included in this analysis.

[17] N.J. Pension and Health Benefits Study Commission, A Roadmap to Resolution, 131 (Feb. 2015), https://www.nj.gov/treasury/pdf/FinalFebruaryCommissionReport.pdf.

[18] Those reforms did not eliminate all forms of double-dipping involving state pensions. Even with the reforms, in limited circumstances, employees can receive more than one state-administered pension from different pension systems. For example, a police officer enrolled in PFRS, prior to retirement, could become a teacher, enroll in TPAF, and earn a second pension in TPAF. Changes to PERS and TPAF created a hurdle for new members seeking enrollment in multiple pension systems at the same time by requiring a 32-hour minimum workweek in each full-time position for enrollment.

[19] GOVERNMENTAL ACCOUNTING STANDARDS BOARD, STATEMENT NO. 73, “ACCOUNTING AND FINANCIAL REPORTING FOR PENSIONS AND RELATED ASSETS THAT ARE NOT WITHIN THE SCOPE OF GASB STATEMENT 68, AND AMENDMENTS TO CERTAIN PROVISIONS OF GASB STATEMENTS 67 AND 68” (June 2015), GASB Statement No. 73.

Waste or Abuse

Report Fraud

Waste or Abuse

Official Site of The State of New Jersey

Official Site of The State of New Jersey