Local Government and School Board Health Insurance Funds: A Report on Conflicts of Interest and Procurement Violations

- Posted on - 09/9/2025

Table of Contents

Introduction

In New Jersey, local governments and school boards are allowed to join together to form Health Insurance Funds—or HIFs—to provide health benefits to their employees. HIFs are public entities bankrolled by taxpayer dollars and managed by public officials. The purpose of the HIFs is to lower costs and increase efficiency by pooling resources and managing insurance collectively, rather than each town or school district handling it alone. Because they manage large amounts of public money—hundreds of millions of dollars a year—state law requires that they follow strict rules when awarding contracts. Those rules are designed to promote fair competition, identify conflicts of interest, ensure transparency, and prevent favoritism and corruption.

Under New Jersey law, when a public contract is expected to be worth more than $12.5 million,[1] it must be submitted in advance to the Office of the State Comptroller (OSC) for review and approval. OSC is responsible for making sure large public contracts follow laws that ensure the integrity of public contracting. In 2024 and 2025, OSC reviewed major proposed contracts from three HIFs: the Southern New Jersey Regional Employee Benefits Fund (SNJHIF), the Schools Health Insurance Fund (SHIF), and the Municipal Reinsurance Health Insurance Fund (MRHIF). These three HIFs together serve hundreds of local governments and school boards across the state and insure over 100,000 public employees and their families. What OSC found in reviewing these contracts was deeply concerning: violations of public contracting laws; improper efforts to steer contracts to preferred vendors; longstanding, undisclosed conflicts of interest; and the use of a fake public entity to attract business. In each case, the result was the same: a concentration of power over taxpayer-funded health benefits in the hands of a single private company—with minimal oversight and limited awareness among the local officials responsible for safeguarding those funds.

At the center of this system is a company called Conner Strong & Buckelew (CSB) and a related entity that operates under the name PERMA. These companies manage the day-to-day operations of many HIFs and provide insurance consulting, brokerage services, and administration. They present themselves as separate and independent companies, but OSC found that CSB and PERMA are effectively the same business operating under two names. Their employees overlap, they share leadership, and the same people work on both sides of the contracts. In many cases, CSB and PERMA help write the rules for how a contract will be awarded—and then compete for and win that same contract. These are classic examples of conflicts of interest, in which a company both influences the decision-making process and stands to benefit from it by steering the contract to itself.

State rules require fund professionals and their employees to disclose conflicts of interest, but that did not happen. There is no indication in many years of records that CSB or PERMA complied with state law requiring such disclosures. Collectively, the repeated conflicts of interest and violations of ethics and insurance rules reflect a widespread disregard of the safeguards designed to ensure impartial decision-making in public contracting and public service.

In the case of SNJHIF, which is based in Camden County and serves nearby counties, OSC found that the HIF’s proposed contract would use a cooperative purchasing process to award contracts to incumbent vendors, while claiming to use a competitive process. By structuring it as a cooperative purchasing process, hundreds of other public entities around the state would be able to piggyback on its contract awards. However, the process was designed in a way that only the existing vendors (called “incumbents”) of the cooperative pricing system members could realistically win—there would have been no true competition. SNJHIF misleadingly suggested other companies could compete, but SNJHIF officials admitted they had no intention of considering any alternatives. This approach is a misuse of cooperative purchasing and is not permitted by the State’s public contracting laws. Instead of promoting fair competition, the contracts were carefully tailored to keep existing vendors in place. And while SNJHIF is governed by a small group of towns in Camden County, it sought to control purchasing decisions for public employees across the entire state—creating a centralized, statewide health insurance system offering hundreds of insurance plans, privately managed by CSB and PERMA.

At SHIF, which serves over 100 school boards, the problems were different but equally serious. CSB was seeking to renew a lucrative contract with SHIF. The person who managed the process of selecting CSB in the past and who was currently overseeing SHIF’s contracting process is a CSB employee—and a minority shareholder in CSB or one of its affiliated entities. Neither SHIF’s board of trustees nor state regulators were informed of this conflict of interest, as required by law. Over a five-year period, SHIF paid over $36 million to CSB and PERMA, often with overlapping fees charged per employee for different roles CSB held. The lack of transparency, combined with the company’s influence over the procurement process, left SHIF’s members—and their taxpayers—with little meaningful oversight of how contracts were awarded or how fees were determined.

At MRHIF, OSC evaluated an entity called the New Jersey Health Insurance Fund—known as the “Hi Fund”—a marketing entity that since 2022 has claimed to represent a billion-dollar insurance pool for public employers. It has a logo, a website, and annual reports. But the Hi Fund does not legally exist. It has no board, no public charter, and has never been approved by state agencies. It is in fact a marketing brand created and controlled by CSB and PERMA, designed to look like a legitimate public entity and used to attract business to CSB’s private brokerage services. The Hi Fund’s materials have historically used the names and images of public officials, including HIF chairs, often without their knowledge or consent. MRHIF, using public dollars, paid for some of this marketing, even though its board members were unaware of the Hi Fund’s operations or legal status. The Hi Fund is not even a real business entity, let alone a public entity or an appropriate shared services tool—it is a front used to generate business for CSB. Again, CSB did not disclose this conflict of interest to the insurance funds or state regulators.

Taken together, these findings show that New Jersey’s HIF system, which was created to save money and pool risk, has allowed a single private company to control key decisions about public employee health insurance, including how contracts are written, awarded, and priced. This consolidation of control by a vendor happened without adequate disclosure, competition, or accountability. The result is an unauthorized covert takeover of a core public function by a private entity—and a serious risk to public trust and public dollars.

In response, OSC issues this Report to alert the Governor, the Legislature, regulators, other similarly situated insurance funds, local officials, public employees, and residents that these violations of applicable laws and regulations are undermining the integrity of the HIF system.[2] The Report is necessary to provide transparency and because the HIFs, PERMA, and CSB dispute that any laws have been or are being violated, claim there are no conflicts of interest, and have clearly indicated their intention to continue with business as usual.

Simultaneously, OSC is formally advising SNJHIF and SHIF that they are not authorized to move forward with their proposed contracts until the issues raised here have been fully resolved by the HIFs. This will provide an opportunity for the HIF trustees, who are elected officials and public employees who bear ultimate responsibility for correcting the problems identified in this Report, to ensure compliance with laws and ethical obligations that to date have received insufficient attention. OSC is therefore directing the HIFs and the trustees to independently—without the involvement of vendors who have profit motivations or others tied to those vendors—prepare and publicly adopt plans for correcting the problems identified in this Report within 60 days.

OSC is also referring its findings to the Department of Banking and Insurance (DOBI), the Department of Community Affairs (DCA), the School Ethics Commission, and the Office of Attorney General – Division of Consumer Affairs for further action. OSC additionally recommends that all joint insurance funds—and all local governments that participate in them—conduct reviews of their current vendor relationships, procurement practices, and internal controls, and take any steps necessary to eliminate conflicts of interest and bring their operations into full legal compliance.

When operated properly, HIFs can be a valuable tool for local governments and schools to create efficiency and maximize taxpayer dollars. But, under the law, public employee health insurance must remain a public responsibility—not one outsourced to favored private contractors with hidden interests and outsized influence in the process. This Report is intended to restore accountability, transparency, and lawful governance to New Jersey’s HIF system and to protect the public funds and public trust that make these programs possible.

Background

A. SNJHIF, SHIF, MRHIF, and Their Vendors

State law authorizes two or more local units, whether local units or school boards, to create a self-insurance fund to offer contributory or non-contributory group health insurance or group term life insurance.[3] The law allows “[t]he governing body of any local unit . . . to join together with any other local unit or units to establish a joint insurance fund” by resolution.[4] Each insurance fund formed this way has a chairperson selected internally who leads the fund’s board.[5] These insurance funds are regulated and overseen by the Director of DCA’s Division of Local Government Services (DLGS) and the Commissioner of DOBI.[6]

SNJHIF is a joint insurance fund established in 1993 pursuant to N.J.S.A. 40A:10-36. It includes 52 local government members and, in 2024, operated with a budget of over $70 million. Beginning in May 2024, SNJHIF submitted proposed procurements to OSC, which were submitted as cooperative pricing system procurements through the Health Insurance Cooperative Pricing System (HICPS), with SNJHIF acting as the lead agency. HICPS is a cooperative pricing arrangement that allows member funds to consolidate purchasing to reduce costs and improve efficiency in acquiring health insurance-related services. According to SNJHIF’s submissions, HICPS members include SHIF, the Bergen Municipal Employee Benefits Fund, Central Jersey Health Insurance Fund, Metropolitan Health Insurance Fund, North Jersey Municipal Employee Benefit Fund, and Southern Coastal Regional Employee Benefits Fund.

SHIF is a school health insurance fund created in 2015 when school boards that were previously part of SNJHIF formed their own fund. SHIF now includes 111 member boards of education and in 2024 had a budget of $544.5 million.

MRHIF is a joint insurance fund created in 1999 by several other health insurance funds. It allows these funds to collaborate through a special joint insurance fund to purchase excess health coverage and related services—such as stop-loss insurance and reinsurance—together. MRHIF has seven member funds and operated with a 2024 budget of over $25 million.

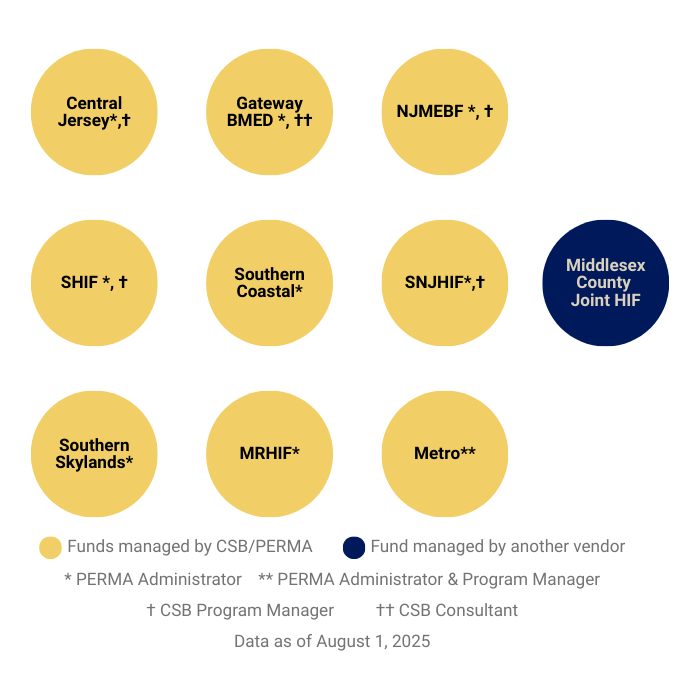

OSC is aware of ten HIFs currently authorized to operate in the State of New Jersey. PERMA/CSB[7] and CSB serve as vendors for SNJHIF, SHIF, and MRHIF, as well as for most local health insurance funds in New Jersey. Of the 10 known HIFs in New Jersey, PERMA/CSB is administrator for 9 (90 percent); CSB or PERMA/CSB are program manager for 6 (60 percent); and CSB is also a contracted consultant for 1 (10 percent). Only one of the ten HIFs does not have any known contracts with CSB or PERMA/CSB. See Appendix A.

Figure 1: Nine of Ten HIFs Are Managed by PERMA/CSB and CSB

PERMA/CSB, acting as the administrator of these funds, is represented by PERMA’s Executive Director (the PERMA ED), who is actually employed by CSB.[8] The three HIFs contract with PERMA/CSB for the PERMA ED’s services as fund administrator. He manages daily operations for SNJHIF, SHIF, and MRHIF, including preparing agendas and budgets, making recommendations to the commissioners, coordinating meetings, working with DOBI, overseeing contracts, managing finances, and handling other administrative tasks. By regulation, the PERMA ED is required to carry out the policies set by the fund and provide its day-to-day management.[9]

CSB also serves as the program manager for SNJHIF and SHIF but not for MRHIF. In addition, CSB functions as the benefits consultant to a number of HIFs. A program manager is defined as “an individual, partnership, association or corporation, other than the administrator, that has contracted with the fund to provide . . . any functions as designated by the fund [commissioners]” which may include:

actuarial services, claims administration, cost containment services, legal services, auditing services, financial services, compilation and maintenance of the fund's underwriting file, coordination and preparation of plan documents, employee booklets and other documents, risk selection and pricing, stop-loss or reinsurance producer services . . . , member assessment and fee development, report preparation, . . . and such other duties as designated by the fund.[10]

In practice, the program manager also acts as the producer, benefits consultant, and broker for the funds.

As discussed further below, while reviewing the procurements submitted by SNJHIF, SHIF, and MRHIF, OSC asked about the relationship between PERMA and CSB. Although public records and their websites initially suggested the two were separate entities—linked only by a common holding company—it became clear from their responses to OSC’s information requests that their operations, personnel, and interests significantly overlapped. Despite an outward appearance of independence, they effectively function as a single entity under CSB’s control.

SNJHIF, SHIF, and MRHIF also use the same attorney and Qualified Purchasing Agent (the HIF QPA), who oversee their procurement processes. The attorney and HIF QPA also support the HICPS cooperative pricing system described above, which was created by a number of HIFs to centralize and streamline purchasing activities. In addition, during this proceeding, SNJHIF, SHIF, and MRHIF were represented by a separate special counsel.

B. The SNJHIF Procurements

1. SNJHIF’s Submissions to OSC

On May 29, 2024, SNJHIF submitted a proposed cooperative pricing system procurement, with SNJHIF as lead agency, entitled “Health Insurance Cooperative Pricing System (ID 297 HICPS) for Medical Claims Third Party Administrator (TPA) and Provider Network Services AmeriHealth offered Plans or Equivalent” (AmeriHealth Procurement).[11] The submission included plan designs and member census data. On June 10, 2024, SNJHIF submitted a second procurement proposal—also under HICPS and with SNJHIF as lead agency—entitled “Health Insurance Cooperative Pricing System (ID 297 HICPS) for Medical Claims Third Party Administrator (TPA) and Provider Network Services Aetna offered Plans or Equivalent” (Aetna Procurement).[12] In addition to these, SNJHIF advised OSC it plans to issue a third procurement using this structure, and its records suggest a fourth similar request for proposals (RFP) may also be in development.

OSC issued initial comments on the AmeriHealth Procurement on June 18, 2024, and on the Aetna Procurement on June 26, 2024. Both identified substantial compliance concerns. On July 17, 2024, SNJHIF informed OSC that its responses to the AmeriHealth Procurement would apply equally to the Aetna Procurement, as both used the same process and documents.

Both procurements were submitted as proposed extraordinary unspecifiable services (EUS) procurements under a cooperative pricing model, with SNJHIF as the lead agency and other New Jersey HIFs as registered members. They were designated as “fair and open”[13] and proposed to proceed under the EUS exception, rather than standard bids to be awarded to the lowest bidder. The procurements aim to select a third-party medical claims administrator (TPA) that will also provide health benefit plans and access to the incumbent provider networks to be used by the local units participating in HICPS through their individual HIFs. The AmeriHealth Procurement included roughly 100 plan designs and indicated that over 300 distinct plans exist, many with only minor differences (e.g., copays, out-of-pocket maximums, eligibility criteria). The documents implied that bidders must either match the incumbent offerings (i.e., AmeriHealth’s existing roughly 100 plan designs and 300 distinct plans) or demonstrate how their offerings would be equivalent to the incumbent offerings. This requirement significantly narrows the field, making it nearly impossible for any bidder but the incumbent to meet the requirements.

Both procurements claim to allow “equivalent” offerings but fail to specify how vendors are expected to demonstrate equivalency. Generally, when “brand name or equivalent”[14] is used in a procurement, as it is here, the expectation is that respondents must match all relevant technical specifications. For example, in this insurance context, a procurement might state that the contracting unit seeks to procure comprehensive health insurance coverage for its employees, comparable to the offerings of a leading insurance carrier, and then detail the desired features, coverage levels, and service quality to be expected, while allowing for alternatives that meet those specifications. Here, the specifications were so specific to the incumbent carrier that there would have been no effective method for an alternate carrier to provide equivalent offerings. Essentially, the specification was so narrowly tailored that it was designed specifically for the incumbent vendor.

Both procurements included technical proposal questionnaires requiring information on performance metrics such as claims processing, network access, reporting, customer service, prior authorization, and auditing. Vendors were also asked to identify any fees and additional value-added services. However, neither procurement included performance data or benchmarks from the incumbents that would allow vendors to assess or demonstrate equivalency in these areas. The listed evaluation criteria were: financial capability, technical ability, managerial ability, and cost. SNJHIF stated that it would award the contract to the most advantageous proposal based on price and other factors but did not explain how or when equivalency would be assessed as part of the evaluation process.

In response to OSC’s question about whether network disruption would be considered in evaluating equivalency, SNJHIF added disruption analysis as an evaluation criterion for the AmeriHealth Procurement. Vendors were required to submit a network disruption analysis as part of their proposal. However, this addition raised further questions: if a vendor’s proposal acknowledges service differences requiring a disruption analysis, it is unclear how that proposal could still be considered “equivalent” to the incumbent. When asked whether SNJHIF had evaluated which TPA carriers could actually be considered equivalent before issuing the procurements, the PERMA ED stated “[t]hat evaluation was not done.” He also acknowledged that the carriers were never actually expected to be equivalent; rather, the procurements were intended to create a menu of options for HICPS members.

Originally, SNJHIF indicated that it would conduct these procurements under the “fair and open” process permitted by N.J.S.A. 19:44A-20.5 and rely on the EUS exception to public bidding, which allows contracts to be awarded based on price and other factors rather than to the lowest bidder. SNJHIF has since indicated a willingness to revise both procurements to comply with applicable cooperative pricing procurement laws and to provide OSC with updated documents. As of this writing, revisions have been submitted for the AmeriHealth Procurement that purport to comply with the public bid and lowest responsible bidder requirements, and OSC provided SNJHIF with comments on its proposed revisions; proposed revisions have not yet been received for the Aetna Procurement.

Because this approach was novel, OSC initially asked SNJHIF whether it had consulted with DLGS or DCA prior to or during the development of these procurements. DLGS, as part of DCA, is responsible for interpreting and implementing the Local Public Contracts Law (LPCL), N.J.S.A. 40A:11-1 to -60, and rules for cooperative pricing systems. SNJHIF’s professionals said they had not discussed the approach with DCA. However, SNJHIF’s attorney did submit a standard cooperative pricing application, which DCA approved.[15]

2. The Governing Laws and Regulations

SNJHIF is a joint insurance fund established under N.J.S.A. 40A:10-36 and must comply with the LPCL under N.J.S.A. 40A:10-38(e). Under N.J.S.A. 40A:10-58, any insurance contract must comply with N.J.S.A. 40A:11-10 and -11, the LPCL’s provisions for cooperative purchasing. Accordingly, since SNJHIF’s cooperative purchasing system is a form of a cooperative pricing system, SNJHIF’s procurements must comply with the LPCL and related regulations, including the general cooperative purchasing systems rules as well as those specific to cooperative pricing systems.

Brand Name or Equivalent Laws

Use of “brand name or equivalent” in public procurements is governed by N.J.S.A. 40A:11-13 and its implementing regulation, N.J.A.C. 5:34-9.2. The LPCL states: “no specifications under this act may: . . . (d) Require, with regard to any contract, the furnishing of any ’brand name,’ but may in all cases require ’brand name or equivalent.’” The LPCL emphasizes that “any specification which knowingly excludes prospective bidders by reason of the impossibility of performance, bidding or qualification by any but one bidder …shall be null and void and of no effect.”[16]

The corresponding regulation clarified that “a contracting agent . . . shall not use a ‘brand name or equivalent’ unless they have knowledge that at least one equal exists” and requires that “[i]f there are no equals or if the nature of the brand name good or service effectively restricts bidders to that single good or service, the contracting agent or purchasing agent must consider the matter subject to the provisions of proprietary goods or services at N.J.A.C. 5:34-9.1.”[17]

The New Jersey Supreme Court has underscored that improper use of “brand name or equal” in bid specifications strikes at “the very bedrock of public contract bidding requirements: free, open and competitive bidding.”[18] In short, if no true equivalent exists, this approach cannot be used.

Cooperative Pricing System Laws

Under the cooperative pricing statute, “[t]he governing bodies of two or more contracting units may provide by joint agreement for the provision and performance of goods and services for use by their respective jurisdictions.”[19] DLGS must approve all cooperative pricing systems and the goods or services covered. Per regulation, “[e]ach registered member who submitted estimates may then order directly from the vendor.”[20] “Registered member” means a contracting unit approved for participation in a cooperative purchasing system.[21] Cooperative pricing systems work by advertising for bids and awarding a master contract to the single lowest responsible bidder for both the lead agency’s needs and those of the participating members. N.J.A.C. 5:34-7.10 requires contracts under this model to be awarded to the “lowest responsible bidder,” which is understood to mean a single entity.[22]

By contrast, procurements under the EUS exception — such as those originally proposed by SNJHIF — are handled through RFPs or quotes and awarded based on “price and other factors,” rather than lowest bid.[23] This distinction raises legal and procedural concerns when the EUS exception is proposed for use within a cooperative pricing structure. Therefore, while procurements under the EUS exception are authorized for contracting units to use when procuring insurance and insurance-related services on their own behalf, the cooperative pricing system regulations do not allow cooperative contracts to be procured using the EUS exception because all cooperative pricing system procurements are required to utilize the low bid procurement process.

C. The SHIF Procurement

1. SHIF's Submission to OSC

On June 10, 2024, SHIF’s QPA submitted to OSC, for pre-advertisement review, an RFP for program manager services (the SHIF Procurement). The procurement uses the competitive contracting method authorized under the Public Schools Contract Law (PSCL).[24] SHIF intends to award a three-year contract to the vendor whose proposal is most advantageous based on price and other factors.

CSB, the incumbent program manager for SHIF and several other health insurance funds managed by PERMA/CSB, is likely to respond to this RFP. In prior procurements, the PERMA ED —who is both Executive Director of PERMA and a CSB employee—administered the process that led to CSB’s appointment, which constituted a clear and unlawful conflict of interest involving a contract under which CSB continues to operate and collect monthly payments. In response to OSC’s current review, SHIF has indicated that SHIF’s QPA and SHIF’s attorney will conduct this procurement to avoid conflicts of interest. SHIF’s counsel has claimed that this change resolves concerns stemming from the relationship between the PERMA ED and CSB.

SHIF covers 111 school boards with a combined annual budget of $544.5 million, providing insurance to a large and growing number of school employees and their families. Over the past five years, the number of individuals covered and total fees paid to SHIF vendors have grown by an average of 85 percent. According to SHIF’s budgets, PERMA/CSB’s and CSB’s contracts during this period were valued at $9.9 million and $26.3 million, respectively. The figure below shows SHIF’s average monthly enrollment and fees paid to vendors from Fiscal Year (FY) 2021 through FY 2025, which demonstrate the market share of fees going to CSB and PERMA/CSB, as well as the increase in the census over the five year period compounded with the increase in per employee per month (PEPM) fees paid to CSB and PERMA/CSB.

Figure 2: Multiple Roles, Surging Fees – CSB Reaped $36 Million over Five Years at Schools Health Insurance Fund [25]

PERMA/CSB (as administrator), CSB (as program manager), and the local entity brokers are each paid a fixed PEPM fee, based on monthly enrollment. CSB also serves as the broker for 16.5 percent of the members across the nine HIFs managed by PERMA/CSB, including SHIF. As a result, CSB can receive up to four PEPM fees for a single covered employee—for roles as administrator of MRHIF, administrator of SHIF, program manager of SHIF, and local broker.[26]

2. The Governing Laws and Regulations

School Board Health Insurance Funds

State law allows boards of education to jointly create self-insurance funds like SHIF to offer group health or life insurance for employees and their dependents.[27] The DOBI Commissioner authorizes the creation of these funds and retains authority to examine their operations.[28] DOBI may suspend or dissolve a fund that violates the law or its approved bylaws.[29]

SHIF is governed by a board of trustees composed of 3 to 15 members, the majority of whom must be employees or officials of member districts. SHIF’s board of trustees is authorized to exercise the full power and authority of the fund. SHIF’s bylaws—approved by DOBI—govern all operational aspects, including how trustees are appointed by commissioners, membership terms of commissioners, governance, claims, risk management, and broker arrangements. School boards join SHIF by resolution and must enter into an indemnity and trust agreement with SHIF.

Each member school board appoints a commissioner to SHIF. Commissioners typically serve two-year terms and may be removed by their local school board at any time. SHIF’s officers (a Chair and Secretary), as well as the remainder of the board of trustees, are elected by the commissioners pursuant to specific terms and procedures described in the bylaws. SHIF currently lists 13 trustees on its website, including a Chair and another officer. Its bylaws, which were approved by DOBI, adopt DOBI’s regulatory definitions of administrator, program manager, and producer and require compliance with the Local Fiscal Affairs Law.[30]

Ethics Rules Applicable to SHIF

The School Ethics Act applies to school boards and administrators, including all SHIF officers and board members. SHIF’s bylaws and contracts require compliance with the School Ethics Act, which emphasizes the importance of public trust and avoiding any conduct that could create the appearance of impropriety.[31]

Under the School Ethics Act and DOBI regulations, school officials involved with HIFs and their immediate family members are prohibited from using their positions to secure unwarranted benefits or employment.[32] They are also prohibited from using non-public information gained through their official role for personal gain or on behalf of any business organization they are associated with.[33]

DOBI regulations further clarify that administrators, such as PERMA/CSB, may not also serve as program managers—the two roles must remain distinct.[34] DOBI regulation, N.J.A.C. 11:15-5.2, defines the roles of administrators, program managers, and producers, and outlines restrictions intended to ensure separation of duties and avoid conflicts of interest:

- Administrator: An employee, member, or contractor who acts as the fund’s executive director, responsible for daily operations and carrying out policies set by the trustees.

- Program Manager: An entity “other than the administrator” that performs designated functions such as actuarial work, claims management, plan documentation, risk analysis, reinsurance negotiation, and fee development.

SHIF’s bylaws mirror these definitions, specifically stating the program manager must be an entity “other than the administrator.” A producer is defined as an individual or entity acting as an insurance agent, broker, or consultant. In addition to the direct prohibition on having the same person or entity act as both the administrator and program manager, DOBI regulations also prohibit program managers and producers—including their officers, directors, and employees—from holding any direct or indirect interest in the administrator, unless they provide written disclosure to the trustees, the fund members, and DOBI.[35] This restriction is reciprocal: administrators must also disclose any ties to program managers or producers. DOBI also requires SHIF to comply with the School Ethics Act and the PSCL.[36] SHIF’s bylaws and vendor contracts reaffirm these obligations. DOBI also requires disclosure of overlapping roles and financial interests. No administrator, program manager, producer, or related personnel may have a financial stake in another fund-related role without notifying the fund’s trustees and members in writing.[37]

DOBI requires insurance funds and their vendors to provide transparency regarding this separation of interests through an annual certification process. Administrators and program managers must submit sworn statements under penalty of perjury, disclosing any direct or indirect financial interests or shared leadership roles in other entities associated with a fund.[38] This includes responses to the following prompt:

I am not and none of the employees, officers or directors of (name of company) is an employee, officer or director of any other administrator, program manager, servicing organization or insurance producer of the Fund, nor do I or any of the employees, officers or directors of (name of company) have a direct or indirect financial interest in any other administrator, program manager, servicing organization or insurance producer of the Fund, except as follows:[39]

They must also confirm whether any such relationships have been disclosed to the fund’s commissioners or executive committee.

D. The MRHIF Procurement

1. MRHIF's Submission to OSC

On May 29, 2024, MRHIF submitted a proposed procurement for OSC’s pre-advertisement review titled “Request for Proposal Re-Insurance/Stop Loss Specifications for Municipal Reinsurance Health Insurance Fund” (the MRHIF Procurement).[40] This procurement sought stop-loss reinsurance coverage for all of MRHIF’s member HIFs. This type of coverage provides protection by reimbursing member HIFs for losses that exceed their premiums, thereby insulating MRHIF and its members from catastrophic claims. After several rounds of revisions to bring the procurement into compliance with public contracting laws, OSC authorized MRHIF to proceed on July 30, 2024. However, OSC clarified that this approval applied only to the procurement process—not to the structure or legality of MRHIF’s membership.

2. The Creation, Operation, and Management of the “Hi Fund” by PERMA/CSB and CSB

During its review, OSC discovered that MRHIF is linked to a public-facing entity known as the Hi Fund. MRHIF maintains a marketing contract for the Hi Fund and manages its website. Despite marketing itself as a health insurance fund created by local governments, the Hi Fund is not a legally recognized entity: it does not provide insurance and has not been authorized under any law. In practice, it is a marketing façade.

The Hi Fund’s 2024 annual report lists nine member HIFs (seven of which are MRHIF members) and identifies nine public officials from those HIFs as Hi Fund Chairpersons. It also includes a New Jersey insurance commission and its chair on the member list. The PERMA ED, a CSB employee, is the administrator of all nine listed HIFs and oversees their operations on behalf of PERMA/CSB. CSB also serves as program manager for at least five of the nine HIFs. The Hi Fund’s “Leadership and Management Team” includes nine CSB and PERMA/CSB employees, including the PERMA ED. Through MRHIF and the Hi Fund, PERMA/CSB and CSB have created a deeply interconnected marketing structure, involving multiple HIFs, overlapping personnel, and hundreds of local government entities.

When questioned, the PERMA ED—MRHIF’s administrator on behalf of PERMA/CSB—told OSC that the Hi Fund is simply a “marketing concept” or “brand,” not a formal business entity. He stated: “I've been referencing the [Hi] Fund as a brand, because I think it’s viewed that it has membership and employees, but it does not. And that's the only reason I’ve referenced a brand, but it’s a marketing concept.” He also claimed he was unaware his name and photo appeared on the Hi Fund website’s “Leadership Team” page.

The Hi Fund website describes itself as a “New Jersey Health Insurance Fund (hi)” founded over 30 years ago to pool resources for public entities and save on insurance. It compares itself to the State Health Benefits Plan and School Employees’ Health Benefits Program and claims a $1 billion annual budget (as of July 2023). It also had a marketing presence at the 2024 New Jersey League of Municipalities Annual Conference.

The Hi Fund’s 2024 annual report mentions a procurement for claims data warehousing. However, when asked about this, the PERMA ED asserted:

- “There is no [Hi] Fund.”

- The data being warehoused belongs to “the entities within MRHIF.”

- MRHIF—not the Hi Fund—issued the procurement.

Notably, the Hi Fund logo also appeared on a procurement submitted by SNJHIF to OSC. When asked why, the PERMA ED and the HIF QPA could not offer a clear explanation.[41]

OSC also spoke with the chairs of SNJHIF, SHIF, and MRHIF about the Hi Fund. Responses included:

- SNJHIF’s chair: “I have never heard of that.”

- MRHIF’s chair: “[I] don’t know anything about the Hi Fund. I’m sorry.”

- SHIF’s chair: “[T]hat’s just the name on the website . . . It’s not, per say [sic], a separate fund.”

3. The Governing Laws and Regulations

The Joint Insurance Fund (JIF) Act, N.J.S.A. 40A:10-36 to -58, allows “the governing body of any local unit” to join with others to form a joint insurance fund.[42] The regulations governing HIFs echo this, permitting local units to create self-insurance funds.[43]

Regulations define a “local unit” as including counties, municipalities, school boards, county colleges, and other contracting units as defined by N.J.S.A. 40A:11-2.[44] A “joint insurance fund” or “fund” is defined as a group of two or more local units that form a self-insurance fund, subject to approval by DOBI under N.J.S.A. 40A:10-36 et seq.[45] Such funds may self-insure or purchase commercial insurance, including reinsurance.

In creating MRHIF, the participating HIFs appear to have been treated as “contracting units” eligible to form a joint insurance fund—though the statutes and regulations define HIFs as “funds,” or “groups,” not as “local units” or “contracting units.”[46] MRHIF’s bylaws state that a group of HIFs formed the fund to jointly purchase excess insurance and related services for additional cost savings.

The Hi Fund was not approved by DOBI or DCA. It was never submitted for approval, and OSC received no documentation about its formation despite multiple requests.[47] PERMA/CSB and CSB continue to assert that the Hi Fund is merely a marketing brand and not a legal entity.

Methodology

OSC initiated individual procurement reviews pursuant to N.J.S.A. 52:15C-10(b) after receiving pre-advertisement submissions from SNJHIF, SHIF, and MRHIF. Given the overlap among these entities and their submissions, OSC conducted joint fact-finding for all three reviews in accordance with N.J.A.C. 19:70-3.11(c). Per N.J.S.A. 52:15C-10 and N.J.A.C. 19:70-3.11, OSC reviewed the initial submissions and requested and received supporting documents and information from the three HIFs. OSC sought to obtain documents, some of which were asserted to be confidential and/or subject to privileges. As is the case in all of OSC’s procurement reviews, OSC advised the HIFs that OSC is statutorily entitled to review all government records, including designated categories of privileged and confidential documents, pursuant to N.J.S.A. 52:15C-14(b). Despite that requirement, the HIFs and their vendors did not provide all responsive documents to OSC.[48]

OSC interviewed the following individuals: on December 12, 2024, Chairperson of SHIF; on December 13, 2024, Chairperson of MRHIF and Chairperson of SNJHIF; on August 5, 2024 and October 29, 2024, the PERMA ED as representative of PERMA/CSB in its capacity as the administrator of the three HIFs; and, on August 5, 2024, the HIF QPA.

On March 7, 2025, OSC sent a letter containing draft findings of law and fact to the HIFs and their vendors, including: general counsel for SNJHIF, SHIF, and MRHIF; special counsel for PERMA/CSB; special counsel for the three HIFs and Chairpersons of the SNJHIF, SHIF, and MRHIF; the HIF QPA; general counsel for CSB; and the PERMA ED. OSC received responses in March and April of 2025 from the HIF QPA, special counsel for the HIFs, and special counsel for PERMA/CSB. A follow-up meeting with the HIFs, PERMA/CSB, and CSB was held on April 22, 2025, and additional written responses were submitted by special counsel for the HIFs on May 7, 2025 and June 11, 2025.

On July 25, 2025, in accordance with its standard procedures, OSC provided the HIFs, PERMA/CSB, and CSB with a nonpublic discussion draft of the full report and invited all of them “to offer comments on any factual inaccuracies and present any other relevant information to OSC.” OSC also provided the Commissioners of DOBI and DCA with advance notice and an opportunity to comment on relevant findings.

OSC reviewed and considered all responses and made revisions where appropriate in preparing this final Report.

On July 29, 2025, the HIF QPA responded to OSC’s draft report by stating that he refused to “cede the independence of the QPA’s role to any elected official . . . or any other interest when it comes to procurement.” OSC addresses the remainder of the HIF QPA’s response, where appropriate, within this Report and in separate correspondence.

Additionally, on August 8, 2025, special counsel for the HIFs and the HIFs’ chairpersons claimed that OSC’s draft report omitted the HIFs’ efforts to revise its procurements and thereby comply with applicable law. This claim is entirely unsupported by any facts. SHIF failed to revise its proposed procurement to address the conflict of interest concerns that OSC raised in its March 7, 2025 letter and the April 22, 2025 meeting. Instead, SHIF has repeatedly denied that any conflict exists, including in its May 7, 2025 letter. Nor has SHIF responded to OSC’s ongoing compliance concerns shared on June 24, 2025. Counsel’s insistence that there is no conflict suggests SHIF intends to award the contract to CSB in the future. For these reasons and OSC’s additional concerns outlined in this Report, OSC will formally deny approval of this proposed procurement. OSC addresses the remainder of special counsel’s specific responses, where appropriate, within this Report and in separate correspondence issued concurrent with the release of the Report.

Lastly, on August 8, 2025, counsel for PERMA LLC and the PERMA ED responded to OSC’s draft report. Counsel asserted that “[f]or decades, PERMA has been in lockstep with its regulator,” referring to DOBI, and “[i]t is unfair to use the inflammatory language that OSC does when my clients’ regulator has signed off on every step of the process.” But as addressed in detail in this Report, PERMA/CSB and CSB’s disclosures to DOBI and to the trustees were not full, complete, or accurate. Instead, the information disclosed to regulators and the HIF’s appointed officials have been inaccurate and misleading throughout much or all of PERMA/CSB and CSB’s history. DOBI cannot be “in lockstep” with PERMA/CSB and CSB when they have failed to provide accurate, honest disclosures.

Findings

A. The SNJHIF Procurements May Not Proceed Because They Do Not Comply with Cooperative Purchasing Regulations and Present Unique Risks.

On behalf of all the members of HICPS, SNJHIF, as the lead agency, proposed two cooperative pricing procurements to engage TPAs who would provide AmeriHealth and Aetna health plans—or their “equivalents”—to participating entities. SNJHIF also intends to issue additional similar procurements tied to other insurance carriers for HICPS, creating a novel procurement structure that no HIF has previously attempted.

The goal of these procurements is for HICPS to offer a catalog of health plan options statewide, effectively establishing a health insurance marketplace controlled by CSB and PERMA/CSB through the lead agency – SNJHIF. SNJHIF is a small fund that serves local governments in Gloucester, Camden, and Burlington Counties. The fund is led by officials from Camden County municipalities, including Barrington, Bellmawr, Brooklawn, Gloucester City, Laurel Springs, Mt. Ephraim, Pennsauken, Runnemede, Somerdale, and Winslow Township. The contracts are intended for use by all HIFs managed by PERMA/CSB and CSB. Despite the statewide reach, the decisions involving the cooperative pricing system, including which vendors to select as fund professionals, would be made by the SNJHIF trustees, who along with PERMA/CSB and CSB, launched New Jersey’s first locally-run cooperative statewide health insurance system with hundreds of health insurance plans available.

OSC finds that the proposed revisions submitted after the April 22, 2025 meeting did, finally, transition the procurements from the EUS exception procurement process to low bid procurements, with pre-qualification regulations to address the HIFs’ “or equal” concerns. However, the revisions were incomplete in multiple ways resulting in ongoing compliance issues including: (1) the proposed revisions sought to incorporate cost proposals into the prequalification analysis, so as to undermine the low bid process; (2) the revisions sought to require proposals from each bidder relating to performance guarantees as part of the bid submission, without explaining how such proposals would be evaluated without further undermining the low bid process; and, (3) the revisions were unclear on how the prequalification process would work, when and how the bid would be publicly advertised, or how the pre-qualification responses would be evaluated to determine whether respondents were qualified to receive, and/or have their bid considered. Each of these continued deficiencies in complying with applicable procurement laws demonstrates an ongoing effort to undermine procurement laws through superficial changes that would allow the HIFs and their vendors to continue to proceed in the concerning manner which is the basis of this Report.[49]

These procurements aim to create a “menu” of plan options, procured through a cooperative pricing system led by SNJHIF, using a process that avoids open, competitive bidding. OSC finds this structure legally impermissible. OSC therefore directs SNJHIF not to proceed.

Additionally, OSC reports that even if the procurements were brought into technical compliance, which to date has not occurred and appears unlikely to occur without fundamental changes, centralizing this level of authority in a single private company raises serious risks not addressed by existing law.

1. SNJHIF’s “Brand Name or Equivalent” Requirement is Improper.

SNJHIF and its fund professionals recognized, and the evidence shows, that SNJHIF’s plan to use “or equivalent” in the HICPS’s TPA procurements did not comply with legal standards. They were fully aware that no true equivalents existed but still planned to use this provision, or a prequalification step with similar intent, to favor existing vendors. The procurement process was tailored to benefit these vendors by misapplying the LPCL’s “or equivalent” rule. The plan was to offer a wide range of insurance plans to HICPSs’ registered member HIFs through just two solicitations, ensuring that the awards went to the current vendors, who were the sole providers of these specific plans. This approach, which would bypass a thorough cost analysis, did not adhere to the legal requirement to award contracts to the lowest bidder or conduct competitive bidding for all plans.

The procurement strategy effectively would have created conditions that make it impossible for anyone other than the incumbent vendors to qualify or bid, violating LPCL principles of open competition and fairness. The LPCL mandates free, open, and competitive bidding, prohibiting sole source contracts unless a genuine equivalent exists. Contracts that deliberately exclude prospective bidders due to impossible conditions are considered null and void.

SNJHIF’s proposed procurements were set up to favor the incumbent vendors, who were the only ones able to meet the required network and other criteria. This lack of a clear process for determining equivalency and omission of technical specifications would have made it difficult, if not impossible, for other bidders to respond adequately. Furthermore, SNJHIF did not explain in the originally proposed RFP or revised prequalification documents how a bidder acknowledging disruption could ever be considered equivalent, indicating that the procurement process proposed was not intended to offer a fair opportunity to non-incumbents. Instead, it seemed to be a formality aimed at securing contracts with specific vendors to provide a menu of plan designs for HICPS’s registered members, while bypassing LPCL compliance under the pretense of the “or equivalent” provision.

2. The Procurements Conflict with Cooperative Purchasing System and Cooperative Pricing System Rules.

N.J.S.A. 40A:11-10 and -11 allow joint insurance funds to enter into cooperative purchasing agreements, create cooperative purchasing systems, and jointly procure services and goods. In doing so, the funds must comply with the Local Fiscal Affairs Law, the LPCL, and other rules and regulations governing the management and expenditure of public funds by local units.[50] A cooperative pricing system, such as HICPS, is a specific form of cooperative purchasing system, subject to both the general cooperative purchasing system regulations and its own discreet cooperative pricing system regulations.

Regulations for cooperative pricing systems require that HICPS issue solicitations via low bid for a single award, with no exceptions. However, HICPS, SNJHIF, and their fund professionals seek to issue a handful of solicitations for hundreds of insurance carrier plan designs and networks that can only be provided by the current incumbents. The originally proposed solicitations would not follow the low bid requirement but would instead use the EUS exception to bidding, allowing evaluations based on price and other factors rather than the lowest price. This approach would result in multiple awards on an incumbent-by-incumbent basis for hundreds of individualized plan designs.

The revised documents submitted to OSC in response to OSC’s initial concerns do little to alleviate the problem. While the revised solicitations appear to facially address the most egregious compliance issue by indicating that the award will be made to the lowest bidder, the end result and lack of competition remain unchanged. The revised documents still seek to award hundreds of plan designs under the terms and conditions designed and administered by the current incumbents. An equivalency analysis occurs during a “prequalification” stage, allowing only carriers who can demonstrate equivalency to receive procurement documents or submit bid proposals. The change from using an EUS exception process with “or equivalent” requirements to a low bid process with an equivalency pre-qualification stage—drafted in such a way that all potential respondents must still demonstrate and certify equivalency with the incumbent’s current contract in order to bid—is intended by the HIFs, PERMA/CSB, and CSB to achieve the same result. This is especially evident given the facts demonstrate these entities were all aware that no equivalent alternatives exist to the current incumbents.

Ultimately, both processes would create a comprehensive catalog of plan designs for use by hundreds of local units whose HIFs are registered with HICPS. This method replaces individualized procurements by local units, reducing transparency, limiting open competition, and consolidating procurement power among hundreds of government entities into one group—namely, SNJHIF and its fund professionals, CSB and PERMA/CSB—contrary to the intent of the LPCL and cooperative purchasing regulations.

OSC concludes that these procurements would not adhere to cooperative pricing system regulations, N.J.A.C. 5:34-7.2 and N.J.A.C. 5:34-7.10, which mandate cooperative contracts be issued as low bids for a single award to the lowest bidder. Instead, HICPS, SNJHIF, and their fund professionals seek to issue solicitations aiming to award plan designs to hand-picked incumbents through a process that evaluates potential respondents based on their equivalency with the incumbent carrier, not just the lowest price as required by law.

OSC also finds that the procurements fail to clearly and adequately notify respondents that these cooperative procurements were designed to require individual local units, not registered with HICPS, to utilize the resulting master contract, including the associated fee structure and cost proposals.

3. The Procurements Present Unique Risks and Exacerbate Conflicts of Interest.

In addition to the above findings that standing alone lead OSC to determine that the procurements may not proceed, OSC additionally notes the following concerns.

The facts show that the proposed procurements would result in control by a single HIF, SNJHIF, acting as the lead agent of a cooperative purchasing system which is administered by the private company PERMA/CSB, technically operated and controlled by SNJHIF’s program manager, CSB. This single HIF, through CSB acting as SNJHIF’s insurance producer, program manager, and administrator, would have sole control over the procurement of all insurance plans, carriers, and networks for its six registered member HIFs. These registered member HIFs represent 298 contracting units, 40,630 local government employees, about 109,700 enrolled persons, and 655 insurance benefit plans, as detailed in the diagrams below.

Figure 3: HICPS’s AETNA Data*

|

Joint Insurance Fund Name |

Local Government Entities |

Employees |

Enrollees |

Benefit Plans |

|

Central Jersey Health Insurance Fund |

22 |

2,183 |

5,894 |

65 |

|

Southern Coastal Regional Employee Benefits Fund |

23 |

4,735 |

12,784 |

77 |

|

Southern New Jersey Regional Employee Benefits Fund |

40 |

3,395 |

9,167 |

138 |

|

Bergen Municipal Employee Benefits Fund |

21 |

1,725 |

4,658 |

70 |

|

Metropolitan Health Insurance Fund |

12 |

2,626 |

7,090 |

32 |

|

North Jersey Municipal Employee Benefits Fund |

25 |

2,093 |

5,651 |

108 |

|

Schools Health Insurance Fund |

103 |

18,128 |

48,946 |

440 |

|

Totals |

246 |

34,885 |

94,190 |

490 |

*Data from proposed procurement OSC File No. 24-812.

Figure 4: HICPS’s AmeriHealth Data*

|

Joint Insurance Fund Name |

Local Government Entities |

Employees |

Enrollees |

Benefit Plans |

|

Central Jersey Health Insurance Fund |

2 |

21 |

51 |

3 |

|

Southern Coastal Regional Employee Benefits Fund |

12 |

1,525 |

4,098 |

39 |

|

Southern New Jersey Regional Employee Benefits Fund |

7 |

278 |

750 |

20 |

|

Schools Health Insurance Fund |

31 |

3,912 |

10,611 |

102 |

|

Totals |

52 |

5,736 |

15,510 |

164 |

*Data from proposed procurement OSC File No. 24-761.

This proposed procurement structure, in which substantial governmental dollars are controlled by, contracted for, and managed by a single private company for profit, presents significant risks. Having interrelated parties, PERMA/CSB and CSB, manage such a massive statewide cooperative purchasing system without clear disclosures of their interconnected interests—while receiving multiple layers of fees and benefits from this single procurement process—expands the role of a small HIF far beyond anything contemplated by law and falls far outside what is authorized by the cooperative purchasing system regulations. Although SNJHIF has expressed a willingness to bring these procurements into compliance with applicable laws,[51] it is unlikely to succeed. But even so, the consolidation envisioned, as evidenced by SNJHIF’s most recently proposed revisions, remains contrary to the intentions, and in many cases the express language of DOBI and DCA when they established the applicable regulations. This consolidation will reduce competition among insurance carriers, diminish transparency of costs and fees paid by local governments, create a single catalog of plan options and fees, and increase the potential for abuse by private contractors without oversight or negotiating power for local units and their employees.

The risk to taxpayers is enhanced by a lack of transparency regarding payments made to incentivize brokers to bring more business to insurance companies. In addition to the fees permitted for producers, program managers, brokers, risk managers, and administrators under the HIFs’ and local units’ procurements and contractual arrangements, there is another way to make money that is evidenced through a recurring compensation disclosure in HIF TPA agreements.[52] This disclosure reserves the insurance carrier’s right to pay additional compensation to producers for bringing in business. This results in brokers being entitled to yet another avenue of compensation from insurance carriers with which the HIFs contract. This additional income creates additional hidden incentives for insurance professionals and comes on the backend, outside of the procurement process and without the approval of any public entity. When the public function of running a statewide government-sponsored insurance program is performed by private actors without full competition and without transparency regarding who is paid for what, taxpayers are likely to come out on the losing end.

OSC refers these issues to DCA and DOBI for any appropriate action.

B. The SHIF Procurement May Not Proceed Due to Undisclosed Conflicts of Interest Involving CSB and PERMA/CSB.

As discussed above, SHIF submitted a procurement for program manager services to OSC for pre-advertisement review. The procurement was for a three-year term using the competitive contracting method authorized by the PSCL. However, the SHIF procurement may not proceed because SHIF’s vendors, PERMA/CSB and CSB, have undisclosed conflicts of interest that should have been reported to both DOBI and SHIF’s Commissioners. These conflicts and the lack of disclosures should be addressed by DOBI and SHIF in accordance with all applicable law. Consequently, OSC cannot approve SHIF to proceed until these issues are fully resolved.

1. PERMA/CSB and CSB Operate as a Single Entity in Violation of Applicable Regulations.

DOBI’s regulations require separate independent entities to serve as administrators and program managers of an insurance fund. This independence supports crucial policy goals such as ensuring checks and balances, preventing conflicts of interest, and promoting transparency and accountability. By separating these roles and segregating duties, the risk of biased and self-interested decision-making is minimized, ensuring that the fund remains solvent, program performance is evaluated objectively, trustees receive sound advice, vendors are selected impartially, and financial decisions are made with objectivity. Distinct entities managing these roles safeguard against misuse of authority and protect the interests of stakeholders, including taxpayers, policyholders, and local governments.

Upon receiving SHIF’s proposed procurement, OSC reviewed the relationship between SHIF’s administrator and program manager, PERMA/CSB and CSB, due to apparent overlaps in their interests, operations, and employees. OSC found that PERMA/CSB is not truly distinct from CSB; PERMA is essentially another name for the CSB employees performing administrator functions for SHIF and other funds, while other CSB employees perform program manager functions. Thus, SHIF’s administrator and program manager are a single entity, not separate entities, contrary to regulatory requirements. CSB failed to disclose this to SHIF and DOBI.

Before 2008, Public Entity Risk Management Administration, Inc. or “PERMA,” operated separately from CSB. A July 2006 letter to DOBI from PERMA advised of a merger with Commerce Insurance Services,[53] stating PERMA would continue as a separate subsidiary with its own staff.[54] The 2006 letter stated that Commerce Insurance Services acted as the program manager for three of the health insurance funds that PERMA also served at that time. The 2006 letter also stated that post-merger PERMA “will continue to operate as a separate subsidiary.” It would operate “under its own name and with its own staff” and committed two PERMA employees to continuing their work with the company for a number of years.[55] Based on available documents and statements, it appears that the separation promised in that letter did not last long, if it was ever implemented at all, and the entity commonly referred to as “PERMA” functions as an alter-ego of CSB, not as a separate entity today.[56]

Eighteen years after the 2006 letter, the PERMA ED, who acts as the administrator of SHIF through its contract with PERMA/CSB, claims to work for PERMA, although he is actually a CSB employee. When the PERMA ED filed financial disclosure statements under the Local Government Ethics Law, he listed CSB as an employer and source of income, without mentioning PERMA. In addition, the PERMA ED testified that senior CSB executives supervise all of his work, and he is a minority shareholder in CSB or one of its affiliated entities. Both the PERMA ED and the current SHIF program manager are included as employees on the organizational chart for “Conner Strong & Buckelew – Employee Benefits – September 2024.” Moreover, the PERMA ED and his CSB colleague, who serves as SHIF’s program manager, report to the same CSB management team, further illustrating their association with CSB.

OSC also found that individuals listed by PERMA/CSB as its employees were actually paid by CSB, consistent with the PERMA ED’s testimony that there is no separate payroll for PERMA/CSB, and its payroll is managed by CSB.[57] The PERMA ED also testified that CSB makes employment-related decisions for PERMA/CSB employees utilizing the CSB employee handbook. Additionally, PERMA/CSB does not have its own physical office space outside of CSB. Although PERMA, LLC, is registered as a separate entity from CSB, it functions as a shell company, with CSB employees performing both administrator functions for PERMA/CSB and program manager functions for CSB.

Documents provided to OSC by PERMA/CSB and the three HIFs include company descriptions, but they do not accurately depict how these two entities operate as one. A 2021 agreement between SHIF and PERMA/CSB refers to PERMA/CSB as a “Division of Conner Strong & Buckelew Companies, LLC.” Furthermore, the resolution adopted by SHIF awarding the current administrator contract to PERMA/CSB describes PERMA/CSB as “a Subsidy [sic; subsidiary] of Conner Strong & Buckelew.” The current contract between SHIF and PERMA/CSB includes documentation stating that the administrator, currently the PERMA ED, is a representative of PERMA/CSB. However, the organizational chart for PERMA/CSB does not list the PERMA ED as an employee of PERMA/CSB.[58]

OSC found a clear example of the lack of separation between PERMA/CSB and CSB in the way the PERMA ED and PERMA/CSB have management procurements for SHIF. The PERMA ED testified that the proposal submitted by PERMA/CSB to SHIF in response to a request for proposals for SHIF’s administrator was reviewed by CSB management before submission. Documents produced by PERMA/CSB also revealed that the PERMA ED, SHIF’s QPA, and SHIF’s attorney communicated with CSB leadership regarding PERMA/CSB’s role in the procurements. This process, which is legally required to be fair, objective, and focused on protecting taxpayer funds, was instead managed by CSB, the incumbent vendor, which reviewed its own proposals and interpreted the procurement rules, ultimately compromising the integrity of the process through bias.

Conflicts of interest do not get any clearer than this. The SHIF’s administrator used his authority and access to the trustees to influence the procurement process in favor of his employer, CSB. It is clear that this was not an isolated incident but rather likely one reason why PERMA/CSB and CSB were publicly presented as separate entities while actually being one. This sort of insider dealing undermines public institutions and jeopardizes taxpayer funds. Ultimately, such practices erode public trust and highlight the need for great caution when lines are blurred between public and private interests.

2. The PERMA ED, CSB, and PERMA/CSB Failed to Disclose Conflicts of Interest to SHIF and DOBI.

DOBI’s regulations require annual disclosures to prevent conflicts of interest and ensure transparency among administrators, program managers, and other parties involved with insurance funds. These regulations aim to prevent self-interested decisions by vendors and maintain independent oversight by prohibiting financial interests without disclosure.

OSC found that the PERMA ED, PERMA/CSB, and CSB violated these regulations by failing to disclose to SHIF and DOBI that PERMA/CSB and CSB are functionally and legally the same entity, and that the PERMA ED is a CSB employee. There were also no appropriate disclosures about PERMA/CSB and CSB’s financial interests, and that the PERMA ED and PERMA/CSB help evaluate whether to retain CSB as program manager on behalf of public entities despite the PERMA ED being a CSB employee. The PERMA ED said he could not recall any disclosures since the 2006 letter to DOBI. In addition, SHIF’s Chair testified that the Board had not been presented with documentation disclosing the relationship between PERMA/CSB and CSB while he has been chair or since SHIF was created in 2015. None of the HIFs received disclosures—MRHIF’s Chair, who also worked with the PERMA ED, testified that it is “common knowledge” that PERMA/CSB and CSB are “two separate organizations.”

In response, PERMA/CSB and the PERMA ED pointed to other filings, such as Ownership Disclosure Statements and Local Government Ethics Law financial disclosure statements (FDSs), submitted pursuant to N.J.S.A. 40A:9-22.6, as fulfilling their disclosure obligations.[59] However, these do not satisfy the annual disclosure requirements.

First, nothing permits them to satisfy the annual disclosure requirements through public bidding filings and other forms. Second, even if that practice was permitted, the Ownership Disclosure Statements made available to OSC for CSB do not disclose any conflicts of interest. They do not even reference PERMA. The Ownership Disclosure Statements made available to OSC for PERMA LLC, an entity that actually does not appear to perform any functions for the HIFs, do not refer to any conflicts of interest and do not reference direct or indirect financial interests. To the extent they reference CSB, there is no language connecting it to PERMA. Lastly, FDSs for the PERMA ED do not disclose conflicts of interest and do not reference PERMA.

State corporate filings do show that PERMA LLC was created in 2011, which could arguably have been misrepresented as the separate PERMA entity in 2006 but for the five-year gap between the representations made to DOBI and the creation of this separate entity. Additionally, as noted throughout this Report, PERMA LLC has never been a party to any of the funds’ contracts or otherwise evidenced itself as a relevant factor in the management of the funds, and PERMA/CSB, which has been the contract party and demonstrated itself as the relevant entity, has never evidenced any real separation or independence from CSB.

PERMA/CSB also asserted that “[i]t is not uncommon for business entities to use variations or short forms of their corporate name,” and “PERMA has been in business in New Jersey for more than 35 years and regularly interfaces with its regulator DOBI as well as DCA, neither of which have ever raised concerns about its name.” Despite PERMA/CSB’s assertion that using variations of corporate names is common, this does not excuse the failure to disclose their functional unity. And the lack of notice to DOBI and DCA about the true nature of PERMA/CSB and CSB’s relationship explains why no concerns were raised by regulators.

Furthermore, SHIF claimed that “neither the School Ethics Act nor the Local Government Ethics Law conflict of interest provisions apply to HIF’s third-party program managers or executive directors.” This is wrong. It would mean that PERMA/CSB, the PERMA ED, the administrator of numerous HIFs including SHIF, and others involved in the daily operations and governance of a public entity, have a unique status within New Jersey government as public entities, vendors, and employees not subject to any conflict of interest laws ensuring they work in the public interest. SHIF acknowledged that DOBI’s regulations would be applicable to the fund’s professionals but argued incorrectly that “those regulations permit entities with a common ultimate corporate parent” to serve as both program manager and administrator “so long as notice of such common interests has been provided to the HIF’s trustees and members.”

Regardless, as explained above, those disclosures did not occur. To the contrary, PERMA/CSB and CSB consistently indicated with regard to conflicts of interest that there were “none.” This is consistent with the SHIF Chair’s response when OSC asked about conflicts of interest—he stated that no conflicts of interest had been presented to the Board by the vendors. At bottom, there is nothing in the record to indicate that DOBI or DCA were ever advised that “PERMA” is really CSB. Equally troubling, PERMA/CSB and CSB’s clients, the public officials who serve on the insurance funds’ boards, were apparently unaware that they were functioning as one entity.

OSC concludes that:[60]

- CSB fully controls PERMA/CSB and its management and operations. PERMA/CSB is an alter ego of CSB, not a separate entity. The PERMA ED is an employee of CSB. None of this was disclosed to the HIFs or DOBI as required by law.

- SHIF, the PERMA ED, PERMA/CSB, and CSB appear to have violated the School Ethics Act by permitting undisclosed conflicts of interest to continue for years.

- SHIF, PERMA/CSB, and CSB appear to have violated the School Ethics Act by allowing PERMA/CSB to be involved in procurements in which SHIF retained CSB. PERMA/CSB—as part of CSB—cannot ethically be involved in any procurement process that concerns CSB or PERMA/CSB.

OSC has determined that SHIF's proposed procurement cannot be approved for release until these issues are fully resolved. OSC refers the matter to DOBI, DCA, and the School Ethics Commission for them to take any action they deem appropriate.

C. MRHIF’s Hi Fund Must be Reviewed by DOBI and DCA, and Any Violations of Producer Laws or Inappropriate Use of Public Resources Resulting from the Hi Fund Must be Resolved, in Accordance With Applicable Laws.

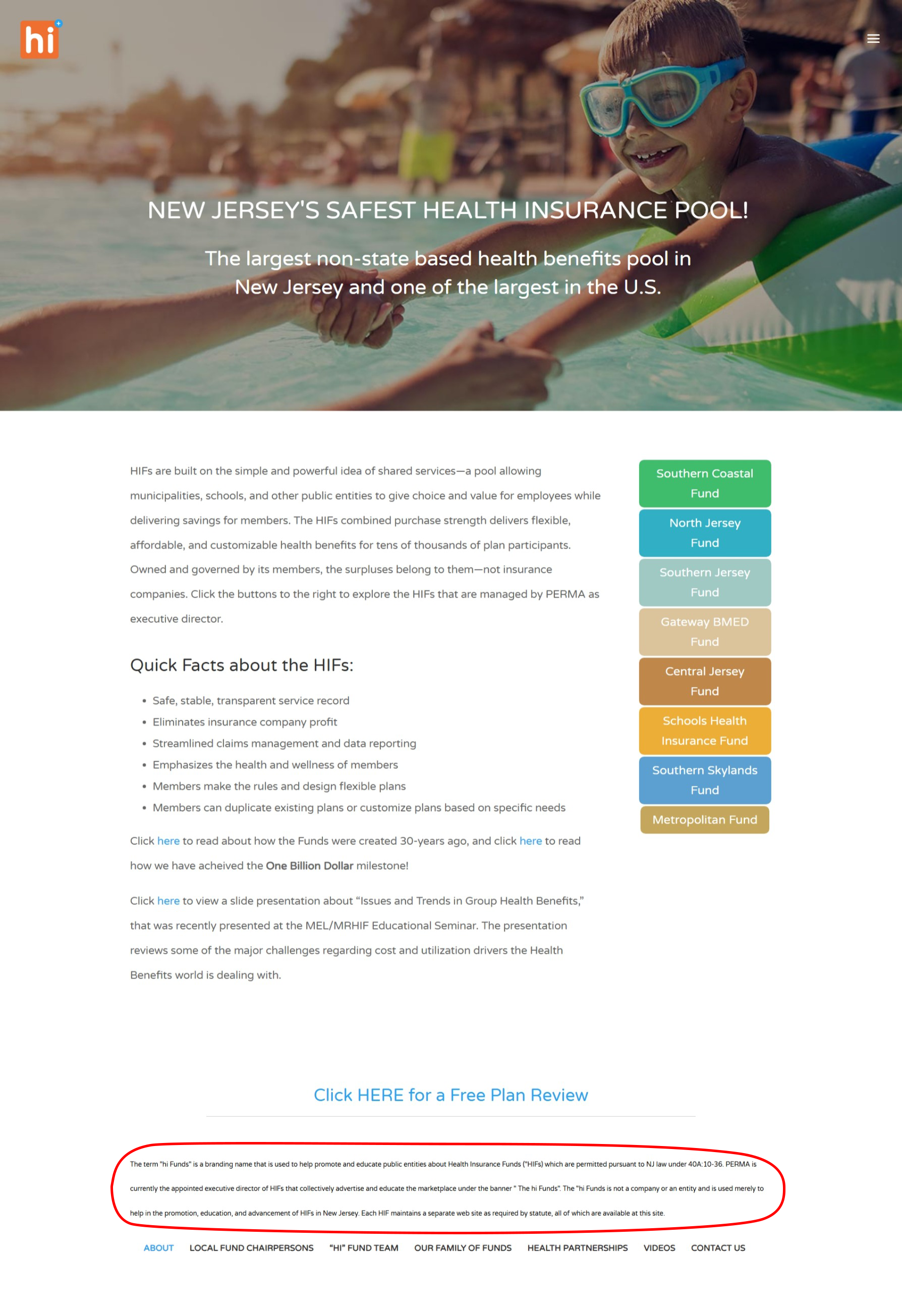

During its review of the procurement submitted by MRHIF, OSC learned that PERMA/CSB created a fictitious entity known as the Hi Fund, or the New Jersey Health Insurance Fund, which serves as a marketing brand for PERMA/CSB, CSB, and the HIFs they manage. The Hi Fund, which has existed since at least 2020, falsely claims that it is “[t]he largest non-state based health benefits pool in New Jersey and one of the largest in the U.S.” It describes itself as a pool designed to offer municipalities, schools, and other public entities choice and value for employees while delivering savings for members. The website compares the fictitious Hi Fund to the State Health Benefits Plan and School Employees’ Health Benefits Program. It also misleadingly states that the Hi Fund operates with a budget of over one billion dollars as of July 2023, which actually represents the combined budget of all nine HIFs, falsely suggesting the existence of a single insurance pool of that size.[61]

When asked about the Hi Fund, the PERMA ED said “[t]here is no [Hi] Fund” and described it instead as a “marketing concept” or “brand.” But the Hi Fund appears to be more than a “brand.” Its website offers a “FREE CLAIMS REVIEW” and includes contact information for two “Team professionals” who have HiFundNJ.com email addresses, but are actually CSB employees. It routinely issued annual reports through 2024. The Hi Fund had a booth at the 2024 New Jersey League of Municipalities Annual Conference, and its logo was featured on an SNJHIF procurement submitted to OSC for review. Neither the PERMA ED nor the HIF QPA could explain the use of the logo in connection with the procurement.

Figure 5: Hi Fund’s Booth at the 2024 New Jersey League of Municipalities Annual Conference

The Hi Fund’s website has also historically displayed the names and pictures of multiple insurance fund chairs and CSB employees, some of whom were unaware the fund existed or that it claimed they were somehow involved with it. The PERMA ED testified he was not aware that his name and picture were included on the website as part of the “Leadership Team” of the Hi Fund. The Chair of SNJHIF, who was also pictured on the site at the time, stated, “the [Hi] Fund. . . I have never heard of that.” Similarly, MRHIF’s Chair, whose picture also appeared on the website at the time of his statement, said, “[I] don’t know anything about the Hi Fund. I’m sorry.”

SHIF’s chair acknowledged it but reiterated that “there’s no quote ‘Hi Fund,’ that is a name on a website.” MRHIF’s chair further stated he was unaware of the Hi Fund’s annual report; he knew MRHIF had a data warehousing project but did not know it was linked to the Hi Fund, and he believed MRHIF’s marketing firm was only being paid to promote MRHIF—not the Hi Fund. MRHIF’s chair appeared unaware of the Hi Fund’s use of MRHIF’s information and data for marketing purposes and that MRHIF funded the Hi Fund’s marketing contract, despite the PERMA ED—who administers MRHIF—reporting that “MRHIF owns the contract” for the marketing firm that promoted the Hi Fund.

Following OSC’s interviews, a disclaimer was added to the Hi Fund’s website, stating:

The term “Hi Funds” is a branding name that is used to help promote and educate public entities about Health Insurance Funds (“HIFs”) which are permitted pursuant to NJ law under 40A:10-36. PERMA is currently the appointed executive director of HIFs that collectively advertise and educate the marketplace under the banner “The Hi Funds.” The “Hi Funds” is not a company or an entity and is used merely to help in the promotion, education, and advancement of HIFs in New Jersey. Each HIF maintains a separate web site as required by statute, all of which are available at this site.

Figure 6: The Hi Fund Website’s “About” Page[62]

In light of OSC's findings concerning the Hi Fund, OSC is referring the Hi Fund and its connections to PERMA/CSB and CSB to DOBI for a determination of whether any of the Hi Fund's activities fall under DOBI's regulatory scope concerning HIF regulations and insurance producer regulations. DOBI should also assess whether disclosures regarding connections between administrators, program managers, and producers must be made to DOBI, fund trustees, and insurance fund members concerning Hi Fund activities. Notably, there are no indications that the financial interests and potential conflicts of interest resulting from PERMA/CSB's and CSB's creation of the Hi Fund have been disclosed to DOBI or HIF trustees.

OSC urges DOBI, DCA, the School Ethics Commission, and Office of Attorney General – Division of Consumer Affairs to investigate and address misrepresentations and misleading statements made in connection with the entity and the use of the likenesses of public officials to generate profits for private businesses—apparently initially without their consent. CSB serves as administrator and program manager, as well as a producer for local governments, and the Hi Fund website combines and promotes CSB's services as a government contractor with its interest in selling insurance. The Hi Fund provides CSB with opportunities to profit using its access to and control over public entities, which is precisely the kind of conduct DOBI's regulations sought to prevent and required to be disclosed. The blurring of lines between public contractor and private business and the false statements made in doing so pose substantial risks to insurance funds, members, and taxpayers.

OSC determined that MRHIF also apparently has a role in the Hi Fund and, after being notified what its vendors have done on its behalf regarding the Hi Fund, has, at a minimum, acquiesced. OSC therefore refers MRHIF to DOBI and DCA to review the propriety of MRHIF allowing its vendors, PERMA/CSB and CSB, to adopt the likeness of public officials for the benefit of the vendors while using public resources. OSC further urges those entities and the School Ethics Commission to evaluate whether public officials from the HIFs who appear on the Hi Fund website and in its materials who have endorsed or acquiesced in their pictures, names, and official titles being used to market a private company as part of a misleading advertising campaign have violated ethics rules.

Corrective Action, Referrals, and Recommendations

This Report reveals that New Jersey’s HIF system, which is intended to consolidate costs associated with local governments and school district health insurance while maintaining governmental control and compliance, has been centralized in the hands of a single entity and has not been effectively overseen by HIF trustees. The undisclosed and unauthorized covert takeover of government functions and assets, where control is transferred to the private sector without proper legal or policy authorization, raises significant ethical and legal concerns, potentially leading to corruption, reduced accountability, and increased costs for reduced public services. Consequently, OSC finds that publicly releasing the findings in this Report is necessary.

OSC reached these findings after a thorough examination of the proposed procurements, guided by the understanding that bidding laws are designed “to guard against favoritism, improvidence, extravagance and corruption” and “to secure for the public the benefits of unfettered competition.” Terminal Const. Corp. v. Atlantic Cty. Sewerage Auth., 67 N.J. 403, 410 (1975); Meadowbrook Carting Co., Inc. v. Borough of Island Heights, 138 N.J. 307, 313 (1994).

Therefore, due to the numerous areas of non-compliance identified in this Report, and to protect the involved governmental units and taxpayer funds allocated for health insurance through the HIFs, OSC finds, in accordance with N.J.S.A. 52:15C-10(b), that the procurements do not comply with applicable public contracting laws, rules, and regulations. In addition to publishing this Report, OSC by separate correspondence is issuing final agency decisions directing SNJHIF and SHIF not to proceed with the proposed procurements pursuant to N.J.S.A. 52:15C-10(b).