A Preliminary Investigation into College Achieve Greater Asbury Park Charter School and its Charter Management Organization

- Posted on - 01/12/2026

Table of Contents

Executive Summary

The Office of the State Comptroller (OSC) has investigated College Achieve Greater Asbury Park Charter School (CAPS Asbury) and its contracted charter management organization (CMO), College Achieve Public Schools, Inc. (CAPS, Inc.), a private non-profit that operates three New Jersey charter schools across eleven campuses. The investigation followed public reports of potential financial mismanagement, illegal procurement practices, and a lack of transparency regarding the use of public funds at CAPS Asbury. While the investigation remains ongoing, this report shares initial findings based on the investigation to date. OSC has uncovered multiple problems that undermine the school’s independent board governance and grant excessive power to CAPS, Inc.

Charter schools like CAPS Asbury are public schools funded by local and state taxes. They operate with more independence than district-run schools. But, like traditional public schools, charter schools must be accountable to the public and must ensure public funds are used in accordance with the law. OSC’s investigation to date shows that CAPS Asbury has fallen short of these obligations in multiple ways.

The CAPS Asbury Board of Trustees (Board), which is responsible for supervising and controlling the charter school, has entered into a contract with CAPS, Inc. that delegates nearly complete control over the school’s core functions—such as curriculum, administration, facilities, executive leadership, and budgeting to CAPS, Inc. The contract locks the charter school into its relationship with CAPS, Inc., making it difficult, if not impossible, for the school to change CMOs without two to three years of advance notice. Together, the extensive delegation of authority to the CMO and the lengthy, difficult process required to terminate the contact, significantly constrain the Board’s ability to govern the charter school.

CAPS, Inc. assumed this role at CAPS Asbury without the contract being reviewed by the Department of Education (DOE). OSC’s investigation revealed that DOE applies different levels of scrutiny to CMO relationships depending on when they are disclosed—conducting rigorous review when a CMO is identified during the charter application process, but requiring only notice, not approval, when a CMO contract is executed after a charter is granted. This gap allowed CAPS Asbury to enter into a management agreement transferring substantial authority to CAPS, Inc. without DOE evaluating the contract terms. By contrast, when CAPS, Inc. was proposed as a CMO in CAPS Asbury’s first charter application, DOE denied the application based in part on concerns about that very relationship.

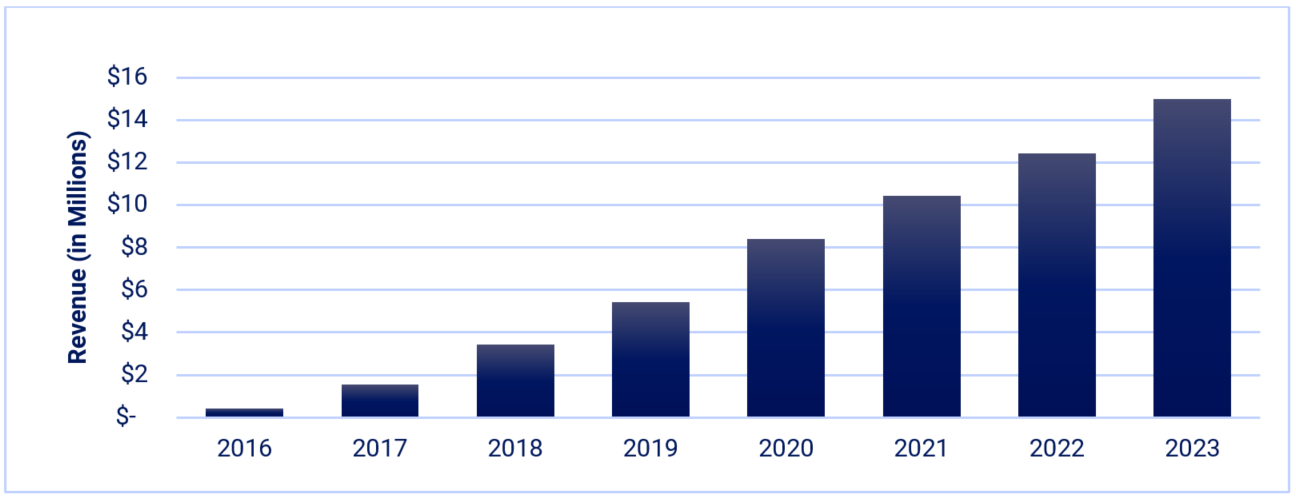

New Jersey law requires public entities and their vendors to be transparent in how public funds are spent, but CAPS, Inc. has failed to meet that obligation. From 2016 to 2023, CAPS, Inc. was responsible for, or oversaw, nearly all of the core functions at three charter schools spread out over eleven campuses. CAPS, Inc. received $57 million in public funds from the schools in its network. But, more than a year after relevant documents were subpoenaed, and even after a court ordered it to comply with OSC’s subpoena, CAPS, Inc. still has not produced the documents. And CAPS Asbury and CAPS, Inc. have also sued OSC in an attempt to avoid turning over an independent investigatory report prepared at their request.

OSC’s investigation confirmed many problems at CAPS Asbury that were reported in the news. This investigation provides additional information regarding the extent of the problems, who specifically was involved, and what role the school’s relationship with CAPS, Inc. played. To date, the following issues have been identified:

• CAPS Asbury violated public contracting laws by approving payments to a company owned by the school Executive Director’s brother-in-law without obtaining competitive quotes or following proper authorization. Unauthorized purchases continued through another vendor who funneled orders back to the related-party business.

• Employees at CAPS Asbury, including some from CAPS, Inc., were involved in illegal purchases with related-party vendors.

• School leadership pressured staff to ensure payments were made despite knowing these transactions were illegal. In what appeared to be an attempt to paper over procurement violations, school staff were directed by a CAPS, Inc. official to obtain second quotes to justify payments to this vendor.

• Cash from uniform sales to parents was mishandled, not deposited into school accounts, and not properly accounted for, putting it at risk of abuse.

• The school Principal improperly rented out school facilities without authorization, keeping poor or nonexistent records of cash payments he collected, that were never accounted for.

• CAPS, Inc. officials were aware of many red flags related to these practices but did not inform or involve the Board of Trustees.

• CAPS Asbury violated anti-nepotism rules by hiring relatives of the Executive Director without proper approvals.

CAPS Asbury and CAPS, Inc. dispute some of these findings and contend that whatever problems did exist were isolated and involved a very small portion of the school’s expenditures. CAPS, Inc. claims that it addressed all of the problems that were found. It insists that there should be no further scrutiny of its practices and argues that OSC’s request for information about its expenditures using public funds is an overreach. OSC has no way to evaluate CAPS, Inc.’s claims regarding the extent of the problems and how effectively they were addressed because CAPS Asbury and CAPS, Inc. are preventing OSC from accessing all relevant facts.

In addition to issuing this report and continuing efforts to obtain records from CAPS Asbury and CAPS, Inc., OSC is referring the findings in this report to DOE to address weaknesses that have given CAPS, Inc. significant leverage and control over a public entity. OSC is also directing CAPS Asbury to prepare a corrective action plan detailing how it will remedy the problems uncovered to date.

Background

A. Charter School Act

The Charter School Program Act (CSPA) of 1995 grants the Commissioner of Education (Commissioner) the authority to establish a system of public charter schools in New Jersey. The CSPA was intended to, among other things, increase the potential for pupil learning, increase educational choices for students and parents, encourage the use of innovative learning methods, and establish a new form of accountability for schools. Charter school operators are given greater autonomy in exchange for greater accountability in student outcomes.

Charter schools are public schools, and the CSPA requires that they adhere to the same “provisions of law and regulation which govern other public schools.”[1] Charter schools are funded with local and state public funds. This combination of funding is on a per pupil basis – districts from which students are drawn transfer a portion of the public funding the district receives to the charter school.

Charter schools are governed by independent boards of trustees and operate under a charter granted by the Department of Education (DOE). Just like a traditional public school, the board of trustees are “public agents” who are tasked with supervising and controlling the charter school.[2] Members of boards of trustees for charter schools are considered school officials and are subject to the School Ethics Act.[3] Charter schools must also comply with the Public School Contracts Law (PSCL), N.J.S.A. 18A:18A-1 to -59.

The terms and conditions of charter enrollment are outlined in a school’s charter issued by the Commissioner. The Commissioner is responsible for granting or denying applications to establish, renew, and expand charter schools. Successful charter school applicants are granted an initial charter for a four-year term. Charter schools must apply to renew their charter every five years.

B. Application Process

New Jersey’s charter school approval process, overseen by DOE’s Office of Charter and Renaissance Schools, occurs in three phases. In phase one, founders submit an application that addresses governance, educational goals, financial plans, and partnerships with education service providers for school management or operation. Founding teams may include teaching staff, parents, or a combination of both. DOE prefers that at least one member of the founding team be an experienced educator, and founding team members are encouraged to reside in the district that the school will serve. DOE evaluates whether applicants have the capacity to open and operate a high-quality school, inviting successful applicants to phase two of the process; those denied may reapply without limit.

Phase two requires a second application with a clear mission statement, demonstrated understanding of the target population, an effective educational program, capable leadership, and sound financial management. After reviewing both phases, the Commissioner issues an initial approval or denial.

Approved applicants then undergo a preparedness review to confirm readiness to open and compliance with all rules, including with regard to facilities, food services, and required trainings. This review ends with an on-site inspection of the school’s program, facility, finances, and leadership, along with interviews and verification of 15 required document categories. Final approval is contingent on successful completion of this step.

C. Accountability

DOE oversees all New Jersey public schools, including both district-run and charter schools, with the mission of ensuring students receive a high-quality public education. The Commissioner evaluates a charter school’s performance on an annual basis and at the four- or five-year mark, before a charter renewal is granted. The annual report and the renewal application submitted by a charter school’s board of trustees are guided by the Charter Office’s Performance Framework. DOE reviews the annual report for red flags. Following the review of a charter renewal application, DOE conducts a site visit and interviews the school’s board members, administrators, teachers, and other school representatives. The renewal application requires the board to demonstrate strong board governance and seeks information about whether the board evaluates school leaders and management vendors. It also asks how any educational service provider supports the ongoing improvement of the school and how it contributes to decision-making, oversight, professional development, and accountability processes.

The Performance Framework sets clear expectations for the charter schools and serves as the basis for school evaluation, monitoring, and intervention. DOE analyzes a charter school’s performance and sustainability based on three areas: academic, financial, and organizational. DOE evaluates a school’s financial viability by looking at near-term financial health, longer term financial sustainability, and fiscal-related compliance. DOE’s yearly financial review of charter school budgets is intended to ensure fiscal viability, and DOE looks closely at whether a charter school ends its school year in a deficit. Similarly, DOE reviews a charter school’s organizational performance by rating its education program and capacity, school culture and climate, board governance, access and equity, and compliance. DOE considers a wide range of evidence in its review of a charter school’s performance, including financial audits, board minutes, policy documents, renewal applications, and interviews with school officials.

D. Educational Service Providers/ Charter Management Organizations

Charter schools may contract with outside vendors—known as educational service providers (ESPs)—for educational and management services. Charter Management Organizations (CMOs) are one type of ESP, typically providing comprehensive school management, including academic programming, staffing, and back-office operations. DOE requires applicants to disclose in their applications if they plan to partner with an ESP and, if so, to submit detailed documentation for review.

DOE evaluates the ESP’s capacity to operate high-quality schools, reviewing its leadership, organizational chart, strategic vision, growth plan, track record, and risk assessment. To assess the proposed relationship, DOE examines the draft contract and a narrative on the ESP’s selection, including roles and responsibilities, scope of services, compensation, financial controls, oversight methods, investment disclosure, and conditions for renewal or termination. Applicants must also disclose potential conflicts of interest and explain how the board will monitor the contract.

If DOE finds the governance structure unsound or questions the arm’s-length nature of its relationship with a CMO, it may exercise its discretion to deny the application. Contracts with ESPs must follow the PSCL. Founders and board members must certify that the school will use an open request for proposal (RFP) process. Boards are responsible for holding ESPs accountable for agreed-upon goals and evaluating them annually, with compliance reported to DOE through its Performance Framework.

E. CAPS, Inc. and College Achieve Greater Asbury Park Charter School

Three “College Achieve” public charter schools have been approved by DOE – College Achieve Central Charter School (CAPS Central), College Achieve Greater Asbury Park Charter School (CAPS Asbury), and College Achieve Paterson (CAPS Paterson). CAPS Central draws students from Plainfield and North Plainfield; CAPS Asbury draws students from Asbury Park, Neptune, and several districts within the greater Asbury Park area; and CAPS Paterson draws students from Paterson. The three CAPS schools operate on eleven campuses.

CAPS Asbury was granted initial charter approval in fall 2016 and opened for the 2017-2018 school year. CAPS Asbury serves approximately 537 students in kindergarten through 12th grades at three facilities: 3455 West Bangs Avenue in Neptune; 700 Grand Avenue in Asbury Park; and 508 3rd Avenue in Asbury Park. All three facilities are subleased from CAPS, Inc., which holds the master lease with the buildings’ owners. For the fiscal year ending (FYE) in 2024, CAPS Asbury’s annual budget was $11,834,905.

All three schools have contracts with and are operated and managed by CAPS, Inc. CAPS, Inc. is a private, non-profit entity formed by Michael Piscal in 2012.[4] He currently serves as its Chief Executive Officer (CEO). CAPS, Inc. directly receives public funds in the form of management fees it charges to public charter schools with which it has contracts. The management contracts between CAPS, Inc. and the three charter schools are substantially the same. CAPS, Inc. charges a fee of 14 to 15 percent of each school’s yearly program revenues for management and operation of the school. In exchange for this management fee, CAPS, Inc. agrees to take on many core aspects of school operations, including implementing the school’s educational program, recruiting, training, budgeting, facilities planning, and any additional services the CMO deems necessary. While the schools are responsible for all business office functions, by hiring or contracting with a school business administrator, CAPS, Inc. oversees the business functions for the charter school. CAPS, Inc., until recently, also provided and compensated the Executive Director of the school.[5]

Almost all of CAPS, Inc.’s revenue is derived from public funds. In FYE 2023, CAPS, Inc. received nearly $14.8 million in public funds for services provided to the three schools. From FYE 2016 to FYE 2023, CAPS, Inc. received $57 million.[6]

Figure 1: Revenue of CAPS, Inc. (FYE 2016-2023) in Millions

A substantial part of the funds received by CAPS, Inc. was paid in salaries to the organization’s executive leadership and the executive directors of the charter schools. The CEO received total compensation of $795,515 in FYE 2023 and a total of $2.35 million from FYE 2020 to FYE 2023. The highest paid executive director of the charter schools received total compensation of $520,674 in FYE 2023. Jodi McInerney, Executive Director of CAPS Asbury (Executive Director), received total compensation of $460,515 in FYE 2023.

Methodology

Pursuant to N.J.S.A. 52:15B and 52:15C, the Office of the State Comptroller (OSC) is responsible for conducting audits, investigations, and reviews of local and state governments, including local boards of education. OSC is also charged with monitoring public contracting. OSC initiated this investigation in summer 2024 following calls for investigations by state legislators in response to a series of press reports starting in May 2024 . Those reports alleged, among other things, that there were conflicts of interest at CAPS Asbury involving public contracting and that the school paid excessive salaries to school administrators.[7]

OSC opened this investigation to examine whether the charter school was compliant with state rules and guidelines and to evaluate whether fraud, waste, or abuse was occurring. OSC also evaluated CAPS Asbury’s relationship with its vendor, CAPS, Inc. OSC focused on the period from CAPS Asbury’s initial approval by DOE in 2016 through FYE 2024. OSC expanded its review in limited areas to include a review of CAPS Paterson and CAPS Central, which also contract with CAPS, Inc.

OSC examined thousands of pages of documents in connection with this investigation, but to date, has been denied much of the documentation it requested from CAPS, Inc.

OSC interviewed two members of the CAPS Asbury Board of Trustees— the Board President, Dr. Dale Caldwell, and the Board Treasurer, Frank Fischer, in February 2025. OSC interviewed high-level CAPS, Inc. employees, including its CEO, Michael Piscal; its former Chief Financial Officer (CFO), David Corso; its current CFO, Glenn Forney; and current and former employees of the school. OSC also interviewed vendors of the school, including the school’s contracted school business administrator and Simonetti and Sullivan, as well as DOE staff and several other individuals.

OSC also subpoenaed both Jodi McInerney, the Executive Director of CAPS Asbury, and Tim McInerney, the school’s Principal, to provide testimony to OSC about these allegations. Both individuals did not appear for interviews. Through counsel, they advised OSC that they would exercise their right against self-incrimination under the Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution and New Jersey law.

OSC also subpoenaed witness testimony and documentary evidence from CAPS, Inc. CAPS, Inc. produced several witnesses for interviews but declined to produce documents OSC subpoenaed in November 2024, instead filing a lawsuit to block OSC’s access to this information. This litigation is pending in the Superior Court, Appellate Division. As a result, in conducting this investigation and preparing this report, OSC did not have access to any non-public information about CAPS, Inc.’s revenue, expenditures, employee lists, or contracts.

During this investigation, OSC also learned that the school and CAPS, Inc. jointly hired a law firm to conduct an internal investigation into the allegations of misconduct by school officials. CAPS, Inc. also submitted testimony to the Senate Education Committee in December 2024, explaining that it “immediately instituted a battery of investigations, reviews, and reforms to ensure these actions were addressed and systems put in place so they would never happen again.” OSC, by subpoena, demanded that the school produce reports and investigative materials related to this investigation. In response, CAPS, Inc. filed a second lawsuit on behalf of itself and CAPS Asbury to prevent OSC from accessing this information. Both lawsuits remain pending at the Superior Court, Appellate Division.

In August 2025, in accordance with its standard procedures, OSC sent a non-public draft report to CAPS, Inc., the CAPS charter schools, DOE, and other impacted parties for review and invited responses to correct any factual inaccuracies, offer relevant information, or submit other comments. Responses from CAPS, Inc. and the CAPS schools that OSC received in September 2025 included additional information germane to aspects of the draft report. As a result, OSC requested additional specific information from CAPS, Inc., the CAPS schools, and DOE. That information was received in late September 2025. OSC conducted several interviews, including an interview of CAPS, Inc.’s CEO, in November 2025. OSC provided an additional draft report to the relevant parties on December 5, 2025 and received additional substantive responses from CAPS, Inc. and DOE on December 16, 2025.

Findings

A. CAPS Asbury Contractually Surrendered Core Governance and Financial Control to CAPS, Inc.

1. CAPS Asbury Ceded Control and Oversight to CAPS, Inc.

CAPS Asbury, through its contract with CAPS, Inc., has delegated almost complete control of the school to CAPS, Inc. This contract, which was not submitted to or evaluated by DOE as part of the charter approval process, undermines the ability of the school board members to function as “public agents” tasked with “supervising and controlling a charter school” as required by N.J.S.A. 18A:36A-3.

The contract provides broadly that the school will use CAPS, Inc.’s “educational management, curriculum, facility and program service.” A copy of CAPS Asbury’s 2024 contract with CAPS, Inc. is attached as Appendix A. According to the contract, CAPS, Inc. assumes responsibility for all administrative activities of the school. It is also responsible for implementing or overseeing the school’s educational program, including the curriculum and pedagogy, Limited English Proficient/English Language Learner (LEP/ELL) education, special education services and programs, school-year and school-day requirements, extra-curricular activities, professional development, student and staff recruitment and discipline, recommendation of education and curriculum consultants, instructional materials, equipment, and supplies. The contract also provides that CAPS, Inc. is responsible for “selection of the school site” and will negotiate the lease terms of the school buildings and sublease those facilities to the school.

The contract further states that CAPS, Inc. will recruit, supervise, and evaluate the school administrator (Executive Director) on behalf of the school and will recommend “the number, positions, responsibilities, and titles of all School personnel” and propose employment practices related to school personnel. The contract provides that CAPS, Inc. will provide and compensate the Executive Director for the school, who will be an employee of CAPS, Inc., in the amount that CAPS, Inc. deems appropriate.[8] Per the contract, CAPS, Inc. would present recommendations for the hiring and replacement of the Executive Director, and the Board may interview “any School Executive Director candidate recommended by CAPS” (emphasis added), which appears to mean that the trustees cannot independently choose their own leadership without permission from CAPS, Inc.

While the school retains limited formal functions, such as holding public meetings and ratifying decisions made by CAPS, Inc., it lacks true control and independent decision-making and oversight in almost all areas, effectively reducing its role to covering the costs determined by CAPS, Inc. Although all school staff are technically employees of the school, they report to the school’s Executive Director, who during the period of this review, was also CAPS, Inc.’s Chief Operating Officer and thus a CAPS, Inc. employee. The contract specifies that while the school is responsible for business office functions, including hiring the school business administrator, oversight of these services must be conducted in cooperation with CAPS, Inc. Moreover, even though the school is tasked with paying for various expenses such as goods, supplies, food services, and employee salaries, CAPS, Inc. retains control over the decisions to incur these costs, facilitated by the Executive Director and CAPS, Inc.’s oversight of school business administration functions.

Lastly, the contract provides that CAPS, Inc. is responsible for presenting a proposed program budget to the Board for each fiscal year, based on assumptions provided by CAPS, Inc. After receiving comments from CAPS Asbury, CAPS, Inc. “shall submit a final budget to the Board for approval, which the Board shall not unreasonably withhold or delay.” The contract makes clear that the Board must receive approval from CAPS, Inc., stating that “[t]he parties will work in good faith to agree on a final program budget no later than June 30th of each year.” Thus, the Board alone, without approval from its vendor, cannot determine how to spend the public funds with which it has been entrusted.

CAPS, Inc.’s control was not just theoretical. Throughout OSC’s investigation, individuals associated with CAPS Asbury and CAPS, Inc. described the relationship between them as one in which CAPS, Inc. had control, rather than the Board. CAPS, Inc.’s current CFO analogized the school to a “franchise” of CAPS, Inc. rather than CAPS, Inc. being a vendor hired by a public entity to perform a service. The former CFO told OSC that the CAPS, Inc. CEO, “pretty much ran the operations of the CMO and the schools [be]cause he dictated who got hired...he was very hands on with the school. . . [t]he way that the organization was structured was [the CEO] made most if not all of the decisions about what was going on, whether it be the CMO or the school.”

This extensive delegation of control to CAPS, Inc., combined with limited powers maintained by the school, diminished the Board’s ability to independently control and supervise the charter school and make strategic decisions. In effect, the Board ceded not just day-to-day management but also the transparency and oversight mechanisms necessary for sound governance.

2. The Contract Contains One-Sided Terms that Significantly Tie the Board’s Hands

In addition to delegating almost all major functions of the school and oversight of the school to CAPS, Inc., the contract includes several lopsided terms that would make it difficult, and to an extent impossible, for the Board to hold the CMO accountable or terminate the contract if necessary to protect students, the school, or taxpayers. These provisions likewise limit the Board’s ability to function in their role as the governing body of a public entity tasked with “supervising and controlling a charter school.” As a result, the CAPS Asbury Board has been unable to independently exercise its duties.

CAPS Asbury’s contract with CAPS, Inc. includes an automatic renewal term that requires the Board to take affirmative action to notify the CMO that it will not renew the contract 18 months before it expires. This means that if the Board decides to replace CAPS, Inc. in June 2026, the 18-month notice deadline would have already passed for the 2027-2028 school year, and the change would not take effect until the start of the 2028-2029 school year.

The Board may also terminate the contract for designated reasons, but it may do so only after providing a six-month cure period followed by an 18-month notice period prior to the termination taking effect. If that combined two-year period concluded during a school year, CAPS, Inc. is entitled to remain on the job and to receive payment under the contract until the end of the school year. This means that CAPS, Inc. can protect itself from being terminated for at least two and possibly three full school years, depending on when during a school year the cure and termination notices are given. It is unreasonable to expect a public entity spending public funds to wait up to three years to change a vendor to which it ceded its powers.

CAPS, Inc., by comparison, may terminate the contract after a 180-day cure period and at the end of the school year “if, upon request of CAPS, the Board fails to adopt recommendations or proposals by CAPS that CAPS believes are necessary for the successful implementation of the CAPS school design.” This imbalance gives CAPS, Inc. significant, inappropriate leverage over the school. The contract further undermines the role of the Board by creating a subjective standard based on what the vendor “believes,” which significantly impedes the Board’s ability to independently oversee or challenge CAPS, Inc.’s decisions. The school’s reliance on CAPS, Inc. is so extensive, and the CMO’s control so entrenched, that the Board is unlikely to challenge the CMO’s approach, expenses, or recommendations.

Taken together, these provisions effectively strip the Board of the ability to exercise independent judgment and respond appropriately when the CMO’s performance, decisions, or priorities conflict with the school’s obligations to students and the public. A charter school board cannot fulfill its statutory role to “supervise and control” the public charter school when the contract governing a critical vendor locks it into years-long delays, imposes subjective standards that empower the vendor over the board, and creates structural disincentives for meaningful oversight.

3. The CMO Contract Violates Public School Contracting Law

Charter schools in New Jersey are public schools entrusted with public funds. As a public school, CAPS Asbury is required to comply with the PSCL. Public contracting laws exist to “secure competition and to guard against favoritism, improvidence, extravagance and corruption.” Twp. of Hillside v. Sternin, 25 N.J. 317, 322 (1957). The laws were enacted to protect New Jersey taxpayers and instill trust that public officials are making well-reasoned and unbiased decisions that serve the public good. Since its inception, CAPS Asbury has repeatedly violated New Jersey’s public contracting laws.

CAPS Asbury was required to procure its contract in accordance with the PSCL. Under the PSCL, CAPS Asbury is required to conduct a publicly advertised low bid solicitation when procuring all goods, services, and construction contracts, unless a specific exception is available. One exception that CAPS Asbury could have used to procure its CMO contract is the competitive contracting process to procure the “operation, management or administration of other services.” N.J.S.A. 18A:18A-4.1(k).[9] The first steps in the process involve obtaining approval from the Division of Local Government Services and the adoption of a resolution by the Board authorizing the use of competitive contracting in lieu of public bidding. CAPS Asbury would then draft an RFP that establishes the scope of the services, deliverables and performance metrics, and the criteria for evaluating proposals. Next, the RFP must be publicly advertised to allow competition, followed by the receipt of proposals. The proposals would be evaluated by a committee or a disinterested official, such as the purchasing agent, counsel, or Business Administrator, which would issue a recommendation to the Board. The Board is responsible for reviewing the recommendation and deciding which proposal to accept. In addition to the PSCL, DOE requires charter schools to use an open RFP process to enter into CMO contracts.

None of these required steps occurred here. The Board’s contract with its CMO was not the result of a publicly advertised fair and transparent process or arm’s-length negotiation that complied with state law. The Board contracted with CAPS, Inc. in 2017 before the school opened for students. CAPS Asbury could provide no evidence that it ever attempted to comply with any of the requirements of the PSCL in procuring this contract. Nor is there any evidence that the school used an open RFP process as required by DOE.[10]

CAPS Asbury further compounded these violations when it improperly renewed the contract multiple times since 2017. The PSCL limits management contracts to a two-year initial term with authorized extensions of up to two years. The automatic renewals in the contract beyond these authorized contract terms violated the PSCL. And, because the contract term never expired, the school never re-procured the services in accordance with the transparency and competition requirements in the PSCL.

OSC also found that CAPS Asbury did not provide management contracts to OSC for review pursuant to N.J.S.A. 52:15C-10.[11] At the time of the initial contract, charter schools were required to submit any contract, including management agreements and leases, to OSC for a post-award review if the total value of the contract exceeded $2 million dollars.[12] If the value of the contract exceeded $10 million at that time, it should have been submitted to OSC for review prior to being advertised.[13] The submission of the contract would have provided an opportunity for an independent state agency's staff attorneys specializing in procurement law to identify and provide guidance about the appropriate solicitation process, required terms that were missing from the procurement documents, and contract terms that violate the law or expose taxpayers to fraud, waste, and abuse. That review would also have identified the unlawful process CAPS Asbury used to enter into the contract. CAPS Asbury’s failure to submit its management contract to OSC further insulated its contract with CAPS, Inc. from scrutiny.

In short, CAPS Asbury disregarded every major safeguard that New Jersey law requires for public contracting from fair, open, and transparent competition. By replacing transparency with a closed, non-compliant process, the Board deprived taxpayers and its own students of the protections that the law was designed to guarantee.

In response to a draft of this report, CAPS, Inc. and CAPS Asbury argued that the CMO contract was designated as an Extraordinary Unspecifiable Services (EUS) contract, an exception to public contracting that provides less transparency and less competition. Indeed, N.J.A.C. 5:34-2.1, which CAPS, Inc. cites, clearly states that the EUS exception “shall be construed narrowly in favor of open competitive bidding wherever possible.” N.J.A.C. 5:34-2.1.

It is also noteworthy that CAPS Asbury and the other CAPS schools, despite claims to the contrary, did not actually use the EUS process. The schools could produce no evidence showing they used EUS, such as a EUS certification, a board resolution with supporting reasons for the award, or publication of a notice of the award of the contract in an official newspaper.[14]

CAPS, Inc. also argues that the CAPS schools are not required to comply with the PSCL and are not subject to OSC oversight because DOE may exempt charter schools from certain state regulations. Putting aside the fact that CAPS, Inc. provided no documentation showing that DOE granted them such an exemption, N.J.S.A 18A:36A-11 does not give DOE the authority to exempt charters from statutory requirements such as the PSCL or OSC’s oversight. Furthermore, although the CAPS schools claim that DOE is aware that charter schools use the EUS exception to procure their CMO contracts, there is no indication that DOE ever formally evaluated or approved such an approach.

4. CAPS Asbury and CAPS, Inc. Have Not Been Transparent about the School’s Financial State

Per their contract, CAPS Asbury is required to pay CAPS, Inc. approximately 14 to 15 percent of CAPS Asbury’s program revenues annually. Through this investigation, OSC found that in multiple years, CAPS, Inc. “forgave” a portion of these fees, in order to avoid CAPS Asbury ending the school year in a deficit. OSC was told that CAPS, Inc. determines how much of its fees to forgive, sometimes hundreds of thousands of dollars, based on how much would be needed for the school to demonstrate a positive fund balance. The amount is exclusively determined by CAPS, Inc., which records the forgiveness as “bad debt” on its books. The Board is generally aware that its debts are being forgiven but plays no role in determining whether it will occur. OSC does not know, and CAPS Asbury has not disclosed in any public reporting, how much, in total, has been forgiven.[15]

This undisclosed “forgiveness” undermines state oversight. DOE reviews charter schools for indicators of short- and long-term financial solvency by reviewing their budgets, select financial records, and the schools’ audited financial statements. DOE was unable to effectively perform those functions here because, despite the Board submitting an annual budget that includes the full cost of the management fee, the school is routinely unable to pay this cost. The forgiveness has never been disclosed to DOE, was not evident in DOE’s annual review, and was reported in the school’s annual financial audit just once. The practice also undermines transparency to the public, including parents of children enrolled in the charter school. The Board has taken no official action to accept the forgiveness of its debts to CAPS, Inc. and thus has not addressed the issue in public meetings. The public is not informed of the true financial condition of the school, because in fact, but for the unilateral actions of its vendor, the school would be unable to pay its costs.

By the terms of its contract, CAPS, Inc. is under no obligation to fund any school deficit or pay school expenses and, thus, has extraordinary leverage over the school, which might otherwise face corrective action, financial monitoring, or possibly revocation of its charter by DOE.

In sum, CAPS Asbury’s reliance on CAPS, Inc.’s voluntary fee forgiveness conceals the school’s true financial condition from regulators and the public. By depending on a private vendor to determine whether a public entity ends the year in deficit, the Board has ceded critical financial control and exposed the school to significant, ongoing risk.

B. Oversight of the Executive Director of CAPS, Inc.

1. The Board’s Insufficient Oversight of the Executive Director

In CAPS Asbury, the Executive Director functions like a district superintendent. All staff report to the Executive Director, and, like a traditional public school superintendent, she would be responsible for executing the strategic direction the Board sets for the school. The law does not require a charter school’s chief school administrator/executive director to be a charter school employee, but DOE expects charter school boards to play a primary role in hiring, overseeing, and evaluating the executive director/chief school administrator. That did not occur at CAPS Asbury.

During the time period under review by OSC, the CAPS Asbury Executive Director was not a school employee, but rather an employee and the Chief Operating Officer of CAPS, Inc. The Board was not directly responsible for the terms of her employment. The contract between the charter school and the CMO stated that CAPS, Inc. was responsible for “supervising and evaluating the school administrator on behalf of the school.”

Consistent with the contract, OSC’s investigation revealed the Board did not evaluate the Executive Director. Board members reported that they provided input to the CMO on her performance, but the Board President had never seen the CMO’s evaluation. Any input regarding the Executive Director by the Board was shared orally and was never written or otherwise documented. This arrangement undermined the Board’s ability to exercise its independent oversight responsibility because it resulted in the vendor, which has an interest in maintaining the contract, evaluating its own senior leader, on behalf of the public entity that hired it. (Both the CAPS Asbury Board President and Treasurer testified that the Executive Director was regularly evaluated and shared their view that if they had recommended her termination, CAPS, Inc. would have complied.)

DOE noted similar concerns during the 2020 charter renewal review. In its renewal application, CAPS Asbury stated the Board annually evaluated the Executive Director, but Board members who were interviewed by DOE could not identify the evaluation tool used or the specific outcomes resulting from the evaluation. As a result, DOE found that on the “Board Capacity” standard, which evaluates whether the Board has the capacity to govern the school effectively, the Board only “partially meets” the standard. DOE noted that the school could produce no written evaluations of the Executive Director.

This is relevant because there were significant, ongoing procurement and legal issues related to the Executive Director, as discussed in Section E below. These issues were exacerbated and likely continued because she was both the head of the charter school and Chief Operating Officer of CAPS, Inc. Without Board oversight, there were few people, other than perhaps the CEO of CAPS, Inc., who had either the authority or ability to adequately oversee her performance and address any issues. And the record showed that even when concerns about troubling practices involving public funds were raised by employees of both the school and CMO, in multiple instances, these concerns were dismissed by CAPS, Inc. leadership and not brought to the Board’s attention. This is further evidence that the CAPS Asbury Board members have delegated too much authority to CAPS, Inc. and have not met their obligation to supervise and control the charter school.

2. The Board’s Insufficient Oversight of CAPS, Inc.

OSC also found that the Board did not effectively oversee CAPS, Inc. Board members reported that they had informal discussions regarding the management contract and the services the CMO provided, but the Board did not have a formal process for evaluating the CMO. DOE periodically reviews the charter school’s performance on various metrics, including academics, financial performance, and equity and organizational soundness, but the Board did not similarly evaluate the CMO even though the CMO was, in large part, responsible for the school’s success or failure in these very areas.

Moreover, as of 2023, DOE began to require, in the school’s annual performance report, that the Board provide specific evidence that it was evaluating its CMO and school leaders. But even though DOE required it, CAPS Asbury has never provided verifiable evidence that it was annually evaluating the CMO contract and never submitted to DOE the evaluation tool the Board claimed to use to evaluate CAPS, Inc. In its August 2023 submission to DOE, the first year it was required, CAPS Asbury omitted the entire section and provided no response. In its August 2024 submission, CAPS Asbury again left it blank.

Both Board members interviewed as part of this investigation highlighted the academic success of the school’s students and the important role the school played in those outcomes for their students as a primary metric to evaluate whether the school’s relationship with its CMO was successful. But the CMO was responsible for more than just academics—its scope included oversight or implementation of almost every major function at the school, including the Executive Director role, finance, budget, recruiting, and supervision of all staff. CAPS, Inc. also became involved in the procurement process at the school, knowing that the some of the purchases violated the law, but took no action to stop those practices. This inaction allowed the abuse of public funds to continue for years without the Board being advised.

Additionally, DOE in its review of the school in connection with the 2020 renewal, noted that the school failed to meet standards in several of the financial and governance categories. These are areas that directly relate to the CMO’s duties and the school’s oversight of the CMO. The Board’s minimal formal oversight of the CMO was insufficient to adequately manage this contract or ensure the public resources were spent effectively.

The role of the school board is to oversee the schools; they do not run the schools or involve themselves in the day-to-day management. But they serve a vitally important function – they are public officials charged with ensuring that the individuals they hire to manage the schools are accountable and that financial practices and other critical policies of the school comply with state law.[16] By ceding both leadership and oversight of its CMO, the Board deprived itself of the ability to detect and prevent problems, undermining its statutory role as the school’s governing body.

3. CAPS, Inc. Did Not Raise Significant Legal and Financial Issues to the Board

CAPS, Inc.’s role at the school contributed to the Board being unaware of problems at the school. Through this investigation, and as detailed in Section E below, OSC found multiple instances in which employees of the school and the CMO identified procurement, legal, and financial issues to CAPS, Inc. that were not shared with the Board. CAPS, Inc. officials were aware of these issues but did not raise them with the Board in a timely manner and did not take effective steps to prevent the problems from recurring.

OSC found that CAPS, Inc. officials knew about purchasing irregularities long before the Board was informed. Beginning in at least 2021, CAPS, Inc.’s CFO approved payments for school purchases, at times knowing they were unauthorized and unlawful. These purchases all involved the same vendor, which should have raised a red flag. Yet, despite multiple warnings to CAPS, Inc.'s management from staff at the school and the school’s own business administrator, no corrective steps were taken. Ultimately, this allowed more than $100,000 in public funds to be paid to a business owned by the Executive Director’s brother-in-law.

Concerns regarding the Executive Director’s deteriorating relationship with the school business administrator, particularly around purchasing practices, were well-known and should have raised red flags, but again, the Board was not made aware of the problem. CAPS, Inc.’s former CFO told OSC that the CMO did not bring these issues concerning the Executive Director to the Board as they arose because “we kind of kept our dirty laundry to ourselves.”

He also testified that if anyone were to bring these issues to the Board, it would have been the CEO of CAPS, Inc., Piscal, who the former CFO described as in control of everything going on at the CMO and at the schools. OSC interviewed Piscal about these red flags and other issues. He explained that he relied on the CAPS, Inc. CFOs and the Business Administrator, who he hired for their expertise and that he was not involved with purchasing at that level.

OSC’s investigation revealed that by summer 2023, CAPS, Inc. officials were aware that there were problems involving cash collected through uniform sales and the unauthorized rental of school facilities by the school’s Principal. By November 2023, CAPS, Inc. leadership was aware that school uniforms may have been purchased from a family member of the Executive Director. Neither the CEO nor any other CAPS, Inc. official advised the Board of these problems.

Piscal testified that in February or March 2024, the new CFO came to Piscal and said, “[w]e have a real problem” and insisted that Piscal listen to him. The CFO told Piscal that CAPS Asbury was making purchases from a vendor who was connected to the Executive Director and that cash at the school was not being handled properly. Piscal asked him to gather more proof before taking any action. Piscal told OSC that he called the Executive Director, who denied wrongdoing. It was not until spring 2024, immediately before a series of press reports, that CAPS, Inc.’s current CFO returned to Piscal with additional proof. Only then did Piscal agree to raise these issues to their attorneys and finally notify CAPS Asbury’s Board. Ultimately, an outside law firm was brought on to investigate, and the Executive Director and Principal were removed shortly thereafter.

CAPS, Inc.’s practice of keeping its “dirty laundry” to itself undermined the Board’s role and prevented the Board from fulfilling its oversight duties and ensuring accountability within the school.

C. Gap in DOE Oversight of CMOs Post-Charter-Approval

OSC’s investigation uncovered a major gap in DOE’s charter-school oversight: when a charter school waits until after approval of its charter by DOE to sign a contract with a CMO, DOE does not review the contract or examine the CMO’s finances and role prior to the contract being signed. This loophole allows CMOs and charter schools to agree to terms that DOE, if it had reviewed the contract and role of the CMO, may have rejected.

DOE has approved three public charter schools that have contracts with CAPS, Inc., but none of the applications DOE approved revealed the schools’ intention to contract with CAPS, Inc. as its CMO. DOE denied all of the CAPS school applications that named CAPS, Inc. as CMO. Piscal claimed that it was his understanding, based on conversations with DOE representatives after the schools were denied, that he could not apply for a charter as a CMO until after CAPS, Inc. was “operational.” The CAPS schools that submitted applications following those discussions with DOE omitted their intended partnerships with CAPS, Inc. And DOE granted their applications and awarded them charters. Soon after receiving approval, and in some cases before the schools had opened for students, the schools entered into a CMO contract with CAPS, Inc.

The CAPS schools were able to enter into contracts with CAPS, Inc. despite DOE’s concerns because after a charter is granted, DOE does not require a school to seek approval before entering into a CMO agreement; the school only needs to notify DOE of the agreement. DOE’s governing regulations focus on fundamental changes to a school’s approved charter—such as mission, governance structure, the number of students or grade level, or educational programs—to trigger a formal charter amendment process requiring DOE approval. However, entering into a management contract with a CMO that transfers significant school leadership and governance functions does not trigger that pre-approval process. DOE explained that it relies on a school’s board of trustees to oversee management contracts post-charter approval. OSC finds that this loophole creates a gap in the State’s oversight of charter schools.

The lack of oversight of CMO contracts post-approval contrasts sharply with the rigorous evaluation process during the application stage. When a CMO partnership is disclosed at that stage, DOE conducts a detailed analysis of the organization, requiring extensive financial and performance data. DOE requires a description of the management structure and key personnel, audited financial statements and management letters, and internal financial statements, including balance sheets and income statements. DOE analyzes this data to look for evidence of financial stability. DOE evaluates whether the organization has the capacity to support a proposed charter school in carrying out the goals stated in their application. DOE also reviews the proposed contract between the school and the CMO to evaluate the governance structure and the way in which the school intends to work with the organization.

After a charter is approved, DOE’s oversight of charter schools focuses mainly on board governance and school operations. Due to this change of focus, a CMO may manage a charter school for an entire school year without DOE ever being aware. In DOE’s view, the Board of Trustees of a charter school is the public entity most responsible for determining whether a contractual relationship is in the best interest of the students and the school. DOE advised OSC that it scrutinizes CMOs at the application stage because it is easier to reject an application than to impose CMO restrictions after a school is already operating. The experience at CAPS Asbury highlights the shortcomings of this hands-off approach.

In response to a draft of this Report, DOE reported that it is evaluating ways to increase oversight when a charter school enters or terminates a contractual relationship with a CMO. DOE noted that as of the 2022-2023 renewal cycle, it began evaluating CMO agreements entered after a charter school’s approval. DOE noted that, between 2023 and 2025, it required charter schools to submit the date of the latest evaluation of the charter school’s CMO, the board’s evaluation tool for the CMO, and a signed and dated contract for the school year.

These are positive steps, but likely inadequate alone to address the problems identified in this report. At the conclusion of this report, OSC recommends steps that DOE should take to address the oversight loopholes identified in this report and increase transparency about how public funds are being spent.

D. CAPS, Inc. Receives Public Funds and Substantially Controls CAPS Asbury But Has Impeded this Investigation

This investigation has demonstrated that CAPS Asbury contracted away control of a public school to CAPS, Inc. and, as will be discussed in section E below, that CAPS, Inc. employees violated procurement laws, enabled nepotism, mismanaged cash, intercepted and apparently retained payments owed to the school, obscured the financial status of the school from regulators, and failed to prevent ongoing misconduct involving public funds despite being aware of it for multiple years.

In view of the dominant role it plays with public schools, and its receipt of tens of millions of dollars in public funds in recent years, New Jersey taxpayers plainly have an interest in obtaining information from CAPS, Inc. in order to identify and address any other areas of fraud, waste, and abuse involving those public funds. CAPS, Inc. though has stalled OSC’s investigation by failing to produce documents relevant to OSC’s investigation. And CAPS Asbury and CAPS, Inc. have sued OSC to avoid compliance with subpoenas from OSC.[17]

OSC does not dispute the right of any entity that receives a subpoena to contest it, but many of the arguments CAPS Asbury and CAPS, Inc. have made here, especially given the problems they have acknowledged, are plainly inconsistent with state law. The two entities continue to receive public funds while they contest the right of OSC to obtain access to documents that would assist taxpayers and policymakers in evaluating whether they have wasted public funds. The litigation is a matter of public record. OSC shares this information in this report because the investigation to date is unavoidably incomplete and taxpayers and policymakers are entitled to know why that is.

In court filings, CAPS, Inc. misrepresents its role with the charter schools it runs. As noted above, OSC was told that the CAPS, Inc. CEO was in charge of decision-making for the CMO and the school and was essentially in charge of everything that went on at the school. Ignoring Piscal’s role and the substantial leverage that CAPS, Inc. has over CAPS Asbury, the CMO claims that it is simply “a private entity who assists charter schools” and relies on absurd interpretations of legislation, claiming that “CAPS, Inc. does not receive public monies from the executive branch, it receives a contracted-for percentage management fee payable by the charter schools it works with – whose funding comes from local tax levies and funds payable by the board of education for the district the charter school(s) operates within.”

CAPS, Inc. argued in court filings that inquiries regarding how it has spent the public funds it received are “quintessentially Orwellian” and that “OSC wishes to assume the role of Big Brother and invasively dive into the private records of a private, nonprofit entity, merely because it has a contract with a public entity.” CAPS, Inc. contends that the State’s interest in tracing taxpayer funds ends once the money leaves the three charter schools’ bank accounts:

What private vendors have or have not done with public dollars once received is irrelevant to the mission of OSC. The enquiry should be, if OSC truly cares about the flow of public funds from the executive branch to private contractors, is to determine how those funds were requested, allocated, and authorized within the executive branch itself. Yet, OSC will ask this Court to uphold the validity of its fishing expedition.

The CMO also contends that “[a]s a private entity, CAPS, Inc. enjoys a right of privacy in its confidential and proprietary business and financial records.” This is inconsistent with state law, which specifically requires vendors to make their business records available to OSC, as a condition of receiving public funds and as part of the State’s commitment to provide “oversight functions that strengthen public accountability with the goal of increasing public trust and confidence that every tax dollar collected by government is spent wisely and well.”[18]

By making these and similar arguments, CAPS, Inc. has contended it is not required to comply with any part of OSC’s November 2024 subpoena seeking information about its operations and expenditures. Even after a trial court in June 2025 rejected CAPS, Inc.’s request to quash the full subpoena and directed it to turn over documents and data involving CAPS Asbury to OSC (but not the other charter schools), the CMO instead filed an appeal.

In an extraordinarily unusual move, in April 2025, CAPS, Inc. filed a second lawsuit against OSC – this one specifically on behalf of CAPS Asbury. That is, a private vendor sued on behalf of a public entity, with the public entity’s support, to prevent the public entity from complying with a subpoena, claiming that OSC’s efforts to obtain an investigatory report prepared for the two entities violates the law. CAPS, Inc. has argued in court that OSC should not be allowed to access investigatory materials that directly involve the school and the public officials who worked there, even though OSC, in order to uncover fraud, waste, and abuse, is required by law to have access to all public records, including those that are designated confidential and privileged by state law.[19]

These lawsuits have caused a year-long delay in this investigation. Even after identifying red flags involving the misuse of public funds by CAPS, Inc. employees, OSC still has limited insight into how the CMO has spent tens of millions of dollars in taxpayer funds it has received from the public charter schools with which it contracts. CAPS Asbury and CAPS, Inc. wrote an op-ed promising to be transparent[20] but have undermined accountability and transparency by refusing to provide documents to OSC.

New Jersey’s charter school law intends for charters to have the same governance and accountability standards as all public schools. A non-profit that has received nearly all of its $57 million in revenues from seven years’ worth of public funds and exercises sweeping control over three public charter schools, including CAPS Asbury, is using its status as a non-governmental entity to hide what it has done with public funds. CAPS, Inc. has set forth legal theories that, if accepted, would annually put hundreds of millions of taxpayer dollars beyond the reach of public accountability once they leave a school’s bank account. This position conflicts with the public nature of charter school funding and undermines the State’s ability to protect public funds.

The risks extend well beyond this single network. If DOE allows this arrangement to stand, without using its regulatory powers to require transparency, it would set a precedent for other CMOs to structure contracts in ways that funnel all operational authority and public funds through private hands, then claim immunity from public oversight. The harm to transparency, governance, and fiscal integrity would be significant and enduring.

E. CAPS Asbury and CAPS, Inc. Staff Committed Procurement and Ethics Violations and Failed to Account for Cash Paid to the School

Following multiple press reports about conflicts of interest involving CAPS Asbury vendors, OSC initiated an investigation into the school’s procurement practices. As noted above, despite repeated requests, neither the school nor CAPS, Inc. provided all relevant records requested by OSC. The limited records available to OSC and interviews of witnesses with direct knowledge confirmed much of the reporting by the press. OSC’s investigation further uncovered facts that show the extent of those problems, who specifically was involved, and the role that CAPS, Inc. played. Overall, the investigation revealed years of repeated violations of procurement and ethics laws, misuse of cash paid to the school, and self-dealing. OSC reports these findings here and may supplement these findings upon full cooperation by the school and CMO.

1. School Leadership Directed CAPS Asbury to Pay a Related-Party Vendor for Unlawful Purchases Using Public Funds

Beginning as early as fall of 2018, CAPS Asbury’s second school year, the school used public funds to purchase sports and school uniforms, branded clothing, and other branded goods from a screen printing and embroidery business, All Shore. All Shore is owned by the brother-in-law of Jodi McInerney, the then-Executive Director of CAPS Asbury, who is also the brother of Principal Tim McInerney.[21],[22] More than $16,000 of public funds were paid directly to All Shore, creating financial gain benefiting the Executive Director and Principal’s family, which violated policies prohibiting conflicts of interest in school purchasing and public purchasing laws.[23] None of the thousands of dollars of purchases complied with the PSCL.

The PSCL[24] requires schools to make purchases through the school’s designated purchasing agent, usually the school business administrator, using a purchase order authorized by the purchasing agent before the goods are ordered.[25] Upon receipt of a request (commonly called a requisition) for goods or services, the school’s purchasing agent must prepare and sign a purchase order, which is sent to the vendor. The vendor then signs the purchase order and provides the goods and services to the school. Prior to purchasing goods or services that cost more than $6,000, the purchasing agent must obtain at least two competitive quotes.

All Shore repeatedly supplied goods without any prior requisition or purchase order, then submitted months’ worth of invoices—sometimes totaling thousands of dollars—to the business administrator, who had never authorized the purchases. CAPS Asbury staff flagged the issue early; in October 2018, they received more than a thousand dollars in invoices for branded items ordered as far back as June, with no paperwork on file. They alerted Jodi McInerney and the CEO of CAPS, Inc., Piscal. McInerney nevertheless pushed staff to pay her brother-in-law’s company, which was considered to be a “priority vendor”. Charter school staff created purchase orders after the fact so the vendor could be paid. Despite repeated warnings, the pattern of noncompliant purchasing and demands for payment continued until the school stopped ordering from All Shore in January 2020.[26]

2. CAPS Asbury Continued to Knowingly Violate the PSCL, Despite Involving Multiple Senior Leaders, Including through Fabricated Quotes

In 2020, CAPS Asbury started ordering clothing and goods from another vendor, Simonetti and Sullivan, LLC. In total, more than $108,000 in public funds were spent on purchases with Simonetti and Sullivan between FYE 2021 and FYE 2024. But as OSC found, this new vendor used All Shore to fulfill all of these orders.

During this period, according to the owner of the business, her only customer was CAPS Asbury, and all of the orders she received from Tim McInerney for the school were fulfilled by All Shore. She received boxes from All Shore, inserted her invoice in the boxes, and delivered them to the school. She charged CAPS Asbury five to ten percent more than All Shore charged her.

As with All Shore, none of the purchases with the new vendor complied with the PSCL. CAPS Asbury ordered clothing and goods without using purchase orders and did not obtain competitive quotes despite escalating costs that exceeded bid thresholds.[27] Under the new vendor, according to emails, Jodi McInerney continued to pressure staff to pay the vendor for the illegal purchases.

By at least 2021, senior CAPS, Inc. staff were aware that the purchases with Simonetti and Sullivan were not authorized. The school’s business administrator complained to CAPS, Inc.’s CFO on multiple occasions. In 2021, the school hired a former consultant to the newly created position of Operations Director.[28] She too reported that, within a few months, the issues with the vendor became obvious to her and that she raised concerns about the purchases to the CFO.

In 2021, CAPS, Inc.’s CFO began approving purchases made by the school related to this particular vendor. While he initially told OSC that he did not have a role in the school’s purchasing process, he acknowledged he eventually became involved as an intermediary between the school business administrator and the Executive Director. He told OSC he was trying to get Simonetti and Sullivan paid, although he acknowledged that he did not have the authority to actually approve payments for the school. Nevertheless, despite his involvement and multiple individuals raising concerns, the unauthorized purchases continued.

In August 2022, the school submitted 31 unpaid invoices it received from Simonetti and Sullivan to the school business administrator for payment. The invoices involved more than $36,000 in goods, spanning purchases from December 2021 to July 2022, for which there were no requisitions and no purchase orders. At the time, the school had already paid the vendor $26,000 that year. The school business administrator then raised the issue directly with CAPS, Inc.’s CFO reporting that the school could not afford to pay the vendor.

In an apparent effort to paper over the PSCL violations, according to the Operations Director, the CFO directed her to get second quotes for the outstanding invoices[29]. The Operations Director acknowledged to OSC that such a process to obtain quotes for goods purchased six months prior was nonsensical, but she followed the CFO’s directive. She told OSC she directed a staff member who reported to her to obtain second quotes but was not involved in how they were obtained. Ultimately, the owner of Simonetti and Sullivan submitted the competing quotes to support her own invoices.[30]

In mid-January 2023, the owner of Simonetti and Sullivan presented a second set of quotes from another business. She emailed the Operations Director under the subject “Other quote update,” and wrote, “I finally was able to get the quotes to coordinate with the invoices. It wasn’t easy!” The email included a cover sheet matching the quotes with 22 (more than $25,000) of the invoices that the vendor had submitted several months earlier. The 22 quotes provided by Simonetti and Sullivan were purportedly from a screen printing business located in Monmouth County. All of the quotes from this business were a few dollars more than Simonetti and Sullivan’s invoices.

These quotes were fabricated. OSC met with the owner of this separate business, and he reviewed the quotes purportedly supplied by his business. The owner acknowledged that the quotes look like quotes that would be generated by his business, but the owner told OSC he has no record of the quotes. While searching for the quotes, the owner explained it appeared that someone may have entered customer information for CAPS Asbury into the system because it auto-filled, but there were no records of these quotes actually having been generated. The owner of Simonetti and Sullivan told OSC that she occasionally helped out at the other business. She confirmed her email address forwarding the quotes but couldn’t specifically recall sending it. She told OSC she couldn’t recall asking the owner of the other business or any other employee to produce the quotes. When pressed by OSC if she had produced the quotes herself, she stated while she didn’t specifically recall, she conceded that it was possible that she generated the documents herself. She also did not recall who asked her to get the second quotes but that it was someone from the school. (OSC was not able to confirm who at the school directed Simonetti and Sullivan to obtain the quotes.)

The Operations Director forwarded the quotes to the school business administrator for payment, and he forwarded it to CAPS, Inc.’s CFO for approval. The school business administrator’s staff member made clear in her email forwarding the quotes that the second quotes were obtained by the owner of Simonetti and Sullivan. The CFO replied that it was approved. The CFO acknowledged to OSC that he was aware of the unauthorized nature of the purchases and concerns with the bid thresholds, but he was acting only as mediator between the school and the school’s business administrator when “approving” the purchases. While he told the Operations Director second quotes were required, he acknowledged the second quotes produced months after the goods were received were problematic, and that it was not proper for the vendor to obtain second quotes. He again maintained that he was not approving payment to the vendor and that only the school business administrator could authorize payment. Despite knowledge of CAPS, Inc.’s illegal purchases and the sham quotation process, no corrective action was taken and the pattern of unauthorized purchases with this vendor continued.

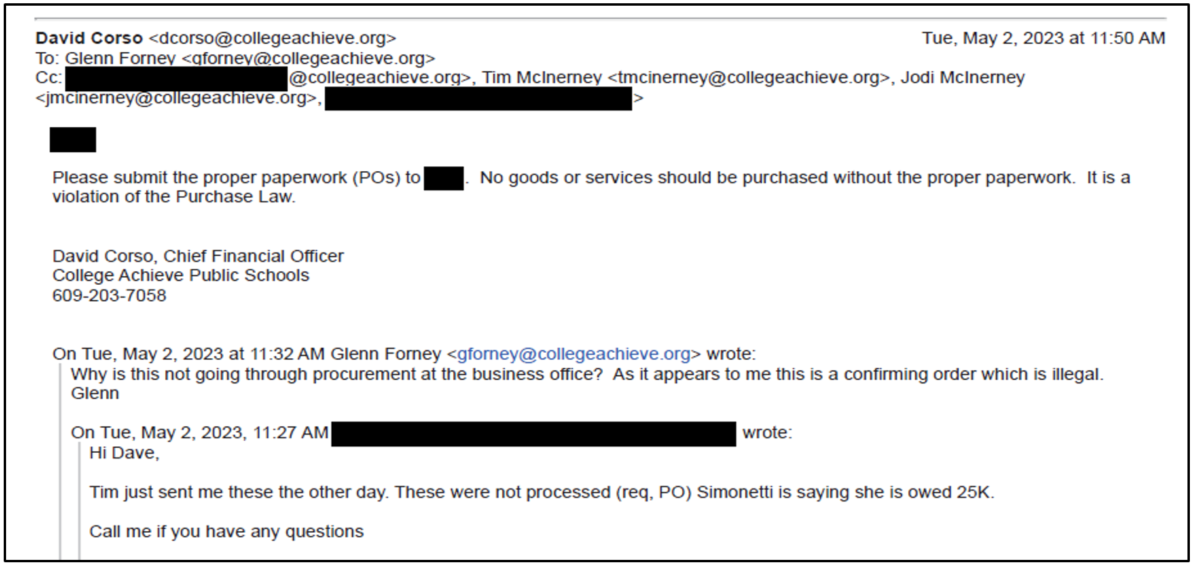

A few months later, in April 2023, invoices for goods ordered and received by the school were submitted for payment and then forwarded to CAPS, Inc.’s CFO for approval. As usual, the purchase was again unauthorized. Around this time, the three CAPS charter schools had entered into a shared service agreement to employ a Chief Budget Officer and were beginning to transition away from the school’s contracted school business administrator in favor of an in-house business administrator at CAPS Asbury. The Chief Budget Officer was copied on the email chain and immediately recognized the illegal nature of the payments, stating in response that “it appears to me this is a confirming order which is illegal.” CAPS, Inc.’s CFO responded to instruct the school that the purchases were unlawful, to submit proper paperwork, and that no goods should be purchased without proper paperwork. Leadership at the school was notified of the unlawful purchasing as the school’s Executive Director and Principal were copied on this email.[31]

Figure 2: Email from CFO to School Leadership

The invoices apparently went unpaid, and in August, Simonetti and Sullivan again requested payment from the school for outstanding invoices. The school’s business administrator became concerned because the school had already spent more than $41,000 with the vendor so far in FYE 2023. And he had concerns that the purchases were unauthorized because CAPS, Inc.’s CFO “usually approved these first” and requisitions were requested and provided prior to paying since “we are never aware [of] these purchases beforehand.” By this time, CAPS, Inc.’s CFO had left the organization and the school’s Chief Budget Officer had just transitioned into a new role as the CFO of CAPS, Inc. While he could not explain to OSC why this was the practice, the unpaid invoices were sent to him for approval by the school business administrator. Again, he recognized that they appeared to be unauthorized purchases, and he emailed the school’s business administrator for more information to confirm how the purchases were made and the total amount of the expenditures with this vendor from FYE 2023. The school business administrator confirmed to the CFO that the orders were unauthorized and that the total amount, including what was already spent that year, exceeded the bid threshold under the PSCL.[32]

The school business administrator told OSC he flatly refused to pay out the invoices from school funds, and after discussions with CAPS, Inc., he was under the impression that CAPS, Inc. would be assuming the cost, directing his staff in email, “do not pay these. CAPS is.” CAPS, Inc.’s CFO reported he did not approve the payments of the invoices and that CAPS, Inc. in fact had not paid for the purchases. When the CFO was asked if he knew of anyone receiving direction on how to deal with the outstanding payment, CAPS, Inc.’s counsel said that was part of an internal investigation and protected by privilege. Nonetheless, Simonetti and Sullivan’s owner told OSC that she received payment for all work for CAPS Asbury, with the possible exception of a “minimal” amount. OSC was not able to ascertain whether the invoices were paid by the school because school records were not maintained with sufficient detail.

While the former CFO confirmed that, prior to leaving CAPS, Inc., both the contracted school business administrator and Operations Director raised concerns to him about purchases by the school, he recalled those issues were limited to the one particular vendor. Both the former and the current CFO told OSC that a remedy for unauthorized purchases to a vendor would include not paying the vendor. But this remedy apparently was not favored, as unauthorized purchases with Simonetti and Sullivan continued for years with the knowledge of the school and CAPS, Inc. The former CFO told OSC his involvement as a go-between became necessary because the relationship between the school’s Executive Director and the school’s business administrator had deteriorated to the point that they were unable to work together. He told OSC that he attempted to hold Jodi McInerney accountable and raised these issues with the CAPS, Inc. CEO, but they were not “well received.” He explained the CEO’s response was that everyone was “picking on” her. The former CFO further explained how Jodi McInerney wanted to get rid of the school business administrator, and the CEO, in turn, went to the Board to advise them not to renew the school business administrator’s contract. While acknowledging that legally only the Board could end the contract with the school business administrator, he explained that as CEO, Piscal ran both the CMO and the school. He added that he was not aware if the Board was informed of the ongoing issues with purchasing.

After the school business administrator’s contract was not renewed, the school brought the position in-house. The school continued its unlawful purchasing from Simonetti and Sullivan until the end of FYE 2024, with the last payments made in April 2024.

3. School Leadership Collected Cash from Uniform Sales and Used it “Off the Books”

The school uniforms illegally purchased from Simonetti and Sullivan were then sold to parents. The school accepted only cash as payment for the uniforms. The cash from the sale of the school uniforms to parents was not properly accounted. It does not appear that much, if any, of the cash generated from the uniform sales was deposited in a school bank account. The school’s accounts show only 18 instances in six years of cash being deposited, with the total amount of those deposits only reaching approximately $13,000. Most of the deposits contained explanations for the cash, including for a book fair, transportation, a fundraiser, and school trips. OSC was able to tie all but three of the cash deposits to a specified use. Three of the 18 instances totaling approximately $2,000 had no explanation. One of them occurred on April 17, 2019 in the amount of about $996; one on September 8, 2023 for $800; and the other on February 5, 2024 for $260.

CAPS Asbury’s approach to handling cash made it essentially an untraceable slush fund. The school’s Operations Director told OSC that she personally observed Jodi McInerney putting cash from the uniform sale in her purse and raised this concern to CAPS, Inc.’s former CFO.[33] She told OSC that thereafter the school kept a locked cash box for the uniform sale proceeds only, which was kept in a locked office. More than one person, including Jodi and Tim McInerney, had access to the keys to the cash box and the office where it was kept. The cash in the box was not reconciled or accounted. The Operations Director told OSC that occasionally Jodi and Tim McInerney would request reimbursement from the cash box, and receipts for purchases were exchanged for cash. These purchases were ostensibly for student rewards and included receipts for pizza and gift cards. However, no accounting or reconciliation of these rewards was ever done.

Although the school did not account for the contents of the cash box, the Operations Director told OSC she maintained copies of the receipts after she left the school. These receipts provided to OSC, spanning the 2023-2024 school year, totaled $11,660. While some of the receipts included items such as pizza, food, and gift cards were consistent with the Operations Director’s understanding of the intended use of these funds, OSC found other questionable “receipts.” For example, Tim McInerney’s name was on two post-it notes, one for $1,830 cash and another for $2,455, and both appeared to be initialed by his wife, the Executive Director. There were no receipts showing why these payments in cash were made.

4. Principal Rented Out the School Gym Without Authorization and Kept Poor or No Records of Payments

OSC’s investigation also revealed that in 2023, CAPS Asbury’s then-Principal, Tim McInerney, entered into a verbal agreement with the owner of a basketball training program to use the school’s gym for an hourly fee. The agreement was not formal – it was never reduced to writing, and although insurance documents were provided, no record of this transaction was kept at the school. The owner paid for the gym in part by giving cash to Tim McInerney. The owner of the basketball training program did not keep a record of the cash payments he paid to Tim McInerney directly but recalled paying cash on about four to five occasions, paying in total around $1,900 to $2,100. OSC’s review of school bank deposits revealed only two cash deposits totaling $1,060 with no description during the period of the rental (fall 2023 to spring 2024).[34]