Hidden in Plain Sight: Systemic Weaknesses Risk Integrity of Police & Firemen’s Pension System

- Posted on - 01/14/2026

Table of Contents

Executive Summary

The New Jersey Office of the State Comptroller (OSC) launched an investigation due to concerns that law enforcement officers in New Jersey were retiring with full pensions or minimal forfeiture despite having engaged in significant misconduct. Law enforcement officers, like other public employees, must serve honorably to receive a public pension. This requirement is enshrined in the law.

Through its investigation, which started with an analysis of publicly available information, OSC identified almost 60 members of the Police and Firemen’s Retirement System who had a record of misconduct and were receiving pension benefits. It was later discovered that 21 of those members had never received honorable service reviews by the pension board prior to being awarded their public pension, even though an honorable service review was appropriate. Since OSC identified these 21 members, almost all have received honorable service reviews as of January 1, 2026, but the pension board only imposed partial forfeiture on three of them.

These were not insignificant cases of misconduct, and, upon learning of their existence, the pension board began the process of conducting the honorable service reviews that should have happened when the member initially retired. Among the 21, there were members who were suspended or demoted prior to retiring pending the outcome of a criminal proceeding or other disciplinary process, and some who agreed to resign their law enforcement jobs as a material term of a settlement agreement. The 21 also included members who were involved in serious, often ongoing misconduct over many years, or had criminal charges filed, and were ultimately required by court order to give up their law enforcement jobs. The most egregious example of a member evading an honorable service review involved a retiring officer who was facing child pornography-related charges and ultimately was convicted.

OSC initially identified these 21 members that slipped through the cracks by reviewing publicly available information, such as news articles and major discipline reporting. Thus, these cases may represent only a portion of a potentially larger issue. Further investigation into these cases revealed weaknesses within the retirement system processes that allowed these members and likely others to evade honorable service reviews. Interviews with Certifying Officers—local employees who are responsible for communicating with the Division of Pensions and Benefits (DPB) upon a member’s retirement—revealed that many of them did not understand their roles in the retirement process, leading to incomplete reporting of misconduct. Additionally, some settlement agreements between law enforcement agencies and officers were found to have deliberately shielded critical information from the pension board, further compromising the integrity of the process for evaluating honorable service.

OSC also found inconsistencies in the decision-making process of the pension board. Even when it received complete information, the pension board’s analyses of misconduct and subsequent decisions about whether to impose pension forfeiture often appeared illogical or inconsistent. For example, in many instances it relied heavily on the member having retired in “good standing” with their law enforcement agency to ensure that members with serious misconduct retired with minimal forfeiture, if at all. This included members who had:

• obstructed and interfered in criminal investigations for personal benefit;

• sent unwanted sexually explicit messages to a female victim;

• repeatedly punched an arrestee after he was handcuffed;

• posted racist messages on social media; and

• were repeatedly suspended for unrelated instances of misconduct.

The pension board’s decision-making necessarily comes with costs to the fund. This pension fund alone has an unfunded liability of over $4.4 billion. For this and other reasons, the existing funds should be preserved for deserving public employees who have served honorably, which constitute the vast majority of members. Instead, OSC found that the pension system is in some circumstances misused as a mechanism to encourage problem employees to agree to retire quietly, passing them off to the state pension system to shoulder the financial burden. When a member with serious misconduct retires without any significant forfeiture of benefits or is permitted to manipulate the system to obtain greater benefits than they are entitled to, the additional costs total hundreds of thousands of dollars over a member’s lifetime. These decisions expose the fund to unnecessary costs and undermine public trust in the system.

Receiving pension benefits for service time that was not honorable is unwarranted under state law and represents a form of pension abuse. And yet, with little exception, there is currently no requirement that a member, upon retiring, must notify DPB or the pension board about their prior disciplinary history, even though such a requirement could alleviate many of the above noted concerns.

For these reasons and those discussed more fully in the report, OSC makes 15 recommendations to the current Police and Fireman's Retirement System (now known as PFRSNJ), DPB, local employers, and the Legislature. OSC also is making referrals to the Office of Attorney Ethics in response to improper terms included in settlement agreements negotiated by attorneys that were reviewed during this investigation. And OSC is referring certain matters to the Attorney General for review.

Background

A. Public Pensions and the Requirement of Honorable Service

In New Jersey, local and state government employees, including teachers, police, and firefighters, are eligible to enroll in a public pension system. Pensions for public employees may induce people to enter and remain in public employment and “render faithful and efficient [public] service.”[1] “They are in the nature of compensation for services previously rendered and act as an inducement to continued and faithful service.”[2]

The Division of Pensions and Benefits (DPB), in the Department of the Treasury, is the administrative body responsible for managing almost all of the State’s public employee pension systems.[3] A notable exception to this, discussed in greater detail below, is the Police and Firemen’s Retirement System (PFRSNJ), which is managed independently by a Board of Trustees, with DPB providing certain day-to-day administrative duties. Each public pension fund has its own set of rules and is overseen by its own board. Most pension plans require an employee to obtain ten years of service credit to vest in the system (i.e., work long enough to earn the right to receive the minimum pension benefits in the future), but the length of service requirements vary for different kinds of retirements and establish the levels of benefits within each fund, among other criteria.[4]

To ensure the financial integrity of the various pension funds, as well as the future availability of funds for those persons who are truly eligible for such benefits, strict eligibility requirements are enforced.[5] In other words, if a member is a few months short of the length of service necessary to be eligible for a certain kind of retirement such as a “service retirement,” the member remains ineligible to receive the benefit unless and until they meet the full service requirement. Neither a pension board nor an employer may waive the service requirement and merely accept a pension contribution in the absence of creditable service.

1. To receive a public pension, every public employee is required to serve “honorably.”

Receipt of any public pension requires more than merely showing up to work each day for the requisite number of years. As detailed in N.J.S.A. 43:1-3(a), all public pensions or retirement benefits are “expressly conditioned upon the rendering of honorable service by a public officer or employee.”[6] If a public employee commits misconduct during their public service which renders that service dishonorable in whole or in part, under N.J.S.A. 43:1-3(b), the pension fund boards are authorized to “order the forfeiture of all or part of the pension or retirement benefits.”[7]

Certain types of misconduct by public employees are so serious that the Legislature has categorically mandated they forfeit their entire pension without the need for further analysis or consideration.[8] Some of the crimes and offenses that result in automatic forfeiture of pension benefits include: criminal coercion; theft by deception, if the amount exceeds $10,000; theft by extortion; commercial bribery; money laundering; false contract payment claims; bribery in official matters; perjury; tampering with witnesses; and official misconduct. As of 2019, other crimes and offenses that require mandatory forfeiture also include sexual assault, sexual contact, and lewdness. Mandatory pension forfeiture can also result when a public employee is convicted of any one of 23 specified state-law crimes, or of a substantially similar offense under the laws of another state or the United States and the crime or offense “involves or touches” that person’s employment.[9]

Most types of misconduct committed by public employees, however, are subject to a more discretionary “honorable service” review by the pension boards. The current statutory and regulatory framework, and the case law interpreting it, contemplate that DPB and the relevant pension board will be alerted by the employer about any employee misconduct upon each member’s retirement and provided with the underlying facts related to the misconduct to allow for this review.[10]

2. Honorable service reviews consist of a multi-factor analysis.

To determine whether a public employee has served honorably, and consider any consequences if the employee has not, pension boards are required to weigh certain statutory factors under N.J.S.A 43:1-3(c). These factors, which are to be considered “in view of the goals to be achieved under the pension laws,” include:

• the member’s length of service;

• the basis for retirement;

• the extent to which the member’s pension has vested;

• the duties of the particular member;

• the member’s public employment history and record covered under the retirement system;

• any other public employment or service;

• the nature of the misconduct or crime, including the gravity or substantiality of the offense, whether it was a single or multiple offense and whether it was continuing or isolated;

• the relationship between the misconduct and the member’s public duties;

• the quality of moral turpitude or the degree of guilt or culpability, including the member’s motives and reasons, personal gain, and similar considerations;

• the availability and adequacy of other penal sanctions; and

• other personal circumstances relating to the member which bear upon the justness of forfeiture.[11]

As part of this weighing process, the pension board is required to evaluate charges of misconduct that occurred at any time during an official’s or employee’s pension membership, or subsequent charges that can be related to the employee’s or retiree’s public employment. In other words, “[t]here is no time limit or statute of limitations after which the Board of Trustees cannot consider charges of misconduct and dishonorable service.”[12] What is more, “every pension grant is subject, as the case may be, either to a deferral of further action or reconsideration if facts become known which bear on the issue of honorable service.”[13]

If the pension board determines that, on balance, a partial forfeiture of pension or retirement benefits is warranted (as opposed to a total forfeiture or none at all), the member’s benefits will be calculated as if the accrual of pension service terminated as of the date the misconduct first occurred. However, if the board finds this calculation renders an unreasonable or unjust result, the pension board has alternative methods available to rectify the result. The board can instead consider:

• forfeiture of salary credit upon which retirement benefits are based;

• forfeiture of retirement system-paid retired State Health Benefits;

• forfeiture of right to participate in the retired State Health Benefits Program (SHBP)/School Employees’ Health Benefits Program (SEHBP);

• reduction in monthly retirement allowance;

• forfeiture of service and/or salary credit in a specific title or rank;

• forfeiture of service in excess of that needed to qualify for a specific retirement benefit; or

• forfeiture of a percentage of the retirement benefit, based on the calculation of the percentage of time which was dishonorable service as compared to the total years and months of service credit.

A member who disagrees with the pension board’s determination may appeal through an administrative process. Ultimately, however, a pension board’s final decisions are afforded great deference by our courts. Those decisions typically carry a “strong presumption of reasonableness,” and will be upheld by the courts unless there is “a clear showing” the board’s decision was “arbitrary, capricious, or unreasonable,” or “lacks fair support in the record.”[14]

B. Police and Firemen’s Retirement System

Of the many pension funds, the Police and Firemen’s Retirement System of New Jersey (formerly PFRS and now PFRSNJ) provides among the largest financial return based on the members’ service time.[15] It is open to all police officers and firefighters appointed after June 1944. Participation of employees in PFRSNJ from municipalities is mandatory. Certain county and state law enforcement job titles are also required to be enrolled in PFRSNJ. Subject to some exceptions, retirement for PFRSNJ members is mandatory at age 65, but members can retire earlier. The pension fund member will typically receive retirement benefits for life, and, in many cases, survivors of members receive survivor benefits.

The current PFRSNJ Board of Trustees became effective February 1, 2019 (the Board). This “new” Board has the “mission to provide secure and sustainable retirement benefits for its members,’ and the “responsibility for the proper operation of the retirement system.”[16] The Board consists of three active police representatives, one elected by the active members of the system, one appointed by the president of the New Jersey State Policemen’s Benevolent Association, and one appointed by the President of the New Jersey State Fraternal Order of Police; three active fire representatives, one elected by the active members of the system, one appointed by the president of the New Jersey State Firefighters Mutual Benevolent Association, and one appointed by the President of the Professional Firefighters Association of New Jersey; as well as one retiree elected from the retirees of the system; and five trustees appointed by the Governor.

At its monthly meetings, the Board considers applications for ordinary disability and accidental disability pensions, deferred retirement and honorable service reviews, among other matters. The Board’s meetings are open to the public subject to the Board’s ability to adopt a resolution to go into a closed session to consider disability applications that involve personal medical and health records, data, reports, and recommendations.[17]

The Board is vested with the general responsibility for the operation of PFRSNJ[18] and is considered a fiduciary of the retirement system with a “Duty of Loyalty to act for the exclusive benefit of PFRS members and beneficiaries.”[19] For this reason, board members are required “to apply the prudent person standard to their conduct, to ensure that appropriate due diligence is undertaken before making either a benefit or investment decision that will affect the specific plan or its [participants].”[20] The Board has the exclusive authority to define a member’s honorable services worthy of pension credit.

Methodology

OSC initiated this investigation based on concerns raised about law enforcement officers in New Jersey retiring with full pensions or minimal forfeiture after being involved in significant misconduct. OSC limited its initial investigation to PFRSNJ members and looked to the Attorney General Major Discipline Report for 2020-2022; PFRSNJ meeting minutes for the same period; news articles about policing, spanning many years; records from the public pensions database; and other sources. Based on those sources, OSC identified a sample of law enforcement officers who appeared to have committed serious misconduct and yet were receiving pension benefits. The identified officers, who retired between 2018 and 2022, belonged to over 40 law enforcement agencies at the municipal, county, and state level, and held varying ranks from officer to chief of police.

Notably, the sample OSC identified during the preliminary investigative process is not comprehensive. In the short period of time OSC was able to identify this sample for further investigation, it found that a significant number of members had evaded honorable service reviews altogether due to weaknesses in certain processes in the retirement system. The true number of members who have evaded the Board’s review is unknown to OSC at this point. However, based on the findings discussed below, the matters uncovered by OSC may be a small sample of an extensive pattern of failures that have allowed members with misconduct to receive their pension benefits without the necessary honorable service review by the Board.

To investigate the identified sample, OSC requested and reviewed case files from DPB and PFRSNJ,[21] as well as internal affairs files and other information received from various law enforcement agencies. OSC interviewed representatives from DPB, PFRSNJ, and the Pension Fraud and Abuse Unit (PFAU), as well numerous other public employees such as Certifying Officers and payroll professionals. Additionally, OSC reviewed relevant statutes, regulations, directives, and case law, and other publicly available materials.

In drafting this public report, OSC carefully balanced the public interest in transparency regarding fraud, waste, and abuse in the public pension system (especially PFRSNJ) with the confidentiality and sensitivity of information that OSC was provided as part of its investigation, including internal affairs files. For this reason, much of OSC’s report is anonymized.[22] OSC has provided confidential referrals where appropriate to other entities for further action and, indeed, most of the matters with undisclosed misconduct that OSC identified to the Board have already been, after disclosure by OSC, subject to honorable service reviews. PFRSNJ has informed OSC that the others are being prepared for the Board and will be scheduled for reviews in the near term.

In addition, as part of this investigation, OSC reviewed many settlement agreements entered into by officers and their employing law enforcement agencies. While certain portions of “end of career” settlements are generally available to the public, OSC was also privy to information related to these matters that is not. In addition, the documents OSC reviewed did not only include career-ending settlement agreements but also agreements that were entered into mid-career to resolve disciplinary matters. OSC sought to review this information because, as discussed above, there is no statute of limitations on misconduct that the Board might consider in evaluating honorable service and the law provides that a member’s retirement can always be reviewed and corrected if a member is receiving more or less than their deserved benefit due to a change or error in the records.[23]

OSC sent a discussion draft of this Report to PFRSNJ, DPB, and the Attorney General’s Office, as well as relevant excerpts to PFAU, to provide them with an opportunity to comment on the facts and issues identified during this review. In preparing this Report, OSC considered the responses received and incorporated them where appropriate.

Findings

A. Major weakness in the retirement process allowed 21 members to evade timely honorable service reviews.

OSC’s investigation revealed significant weaknesses in the retirement processes at multiple levels of government that have interfered with the Board’s ability to consider all relevant information prior to awarding a public pension upon a law enforcement member’s retirement. Some of the root causes of these weaknesses appear related to the sensitivity and confidentiality around internal affairs and criminal investigations, officer misconduct, and related discipline.

Historically, the internal affairs process in New Jersey is highly confidential, and there are only limited exceptions under which officer misconduct and discipline can be disclosed. One of those exceptions is the requirement that this information be shared with DPB. As described above, N.J.S.A 43:1-3(c) explicitly requires that upon retirement from public employment, pension boards will consider, among other factors, a member’s employment history and any misconduct (criminal or otherwise) to ensure the condition of honorable service was met in whole or in part before granting a pension to a retiring member.

The Attorney General recognizes this important exception to the confidentiality of internal affairs records in the Internal Affairs Policies and Procedures (IAPP), a document setting forth policies and procedures that must be adopted by every law enforcement agency in New Jersey. In fact, in 2022, the Attorney General added explicit language highlighting this requirement to ensure compliance with the pension laws. Notably, however, even the most current IAPP does not place on law enforcement agencies the affirmative obligation to share all internal affairs information but rather requires only that the law enforcement agency and officer affirmatively report information to DPB in limited circumstances, such as when an investigation is “pending” or there are criminal charges. Otherwise, the IAPP provides internal affairs information may only be shared upon request from DPB.[24]

This is a small but critical gap in approach, the significance of which is illustrated by the detailed findings below. If the pension board is not affirmatively provided with the information, it will not know to request it in order to evaluate honorable service prior to awarding a pension to a retiring member. In turn, in many instances, the pension board will unknowingly fail to fulfill its statutory and fiduciary duties.

By looking at publicly available information and comparing it to public pension records, OSC identified almost 60 members who had a record of misconduct that were receiving pension benefits. In responding to OSC’s inquiries, PFRSNJ discovered that 21 of those members had never received honorable service reviews by the Board prior to being awarded their public pension, even though an honorable service review was necessary. The Board never received notice of the members’ misconduct. As a result, these members were receiving full pension benefits, in some instances for years, without the Board having the opportunity to review their misconduct and determine whether their service as a law enforcement officer had, in fact, been honorable in whole or in part, and deserving of a public pension without any forfeiture.

The misconduct in many of these cases was very serious, ranging from dishonesty to criminally possessing child pornography, among other criminal and administrative charges. OSC’s review also revealed that, for many of the members, serious misconduct was not an isolated incident, although most of it was never made public. While OSC is unable to provide specific details about the 21 individual members due to the confidentiality concerns described above, the following trends were identified in OSC’s review:

• 13 members were suspended prior to retiring, pending the outcome of a criminal proceeding or other disciplinary process;

• 11 members agreed to resign their law enforcement job as a material term of the settlement agreement;

• 6 members were involved in serious or ongoing misconduct over many years;

• 5 members had criminal charges;

• 3 members were demoted; and

• 2 members were required by court order to give up their law enforcement job.

In response to OSC’s findings, PFRSNJ informed OSC that the Board would be conducting honorable service reviews for each member who should have received that review in the first instance when the member applied to retire years prior. Of the 21 members, almost all have now received honorable service reviews. Notably, as of January 1, 2026, the Board only imposed partial forfeiture for three of the members described above. The Board initially found an additional member’s conduct warranted partial forfeiture, but the Board reconsidered after the member wrote a letter and his full benefits were reinstated.

One member received a greater pension benefit after the review due to a surprising recalculation of creditable service. Adopting the terms of a settlement agreement to which it was not a party, the Board found the member to be eligible for the more lucrative “special” retirement. As discussed more fully below, special retirement is reserved for officers who have served honorably in a law enforcement position for 25 years or more. It comes with a higher monthly pension benefit calculation than a “service” retirement.

As detailed below, the reasons for the breakdown in transmitting necessary information to the Board are many. The costs of the information breakdown, also set forth below, are equally significant.

1. Most Certifying Officers interviewed did not understand or fully appreciate their role in the retirement process and did not provide the required information.

Certifying Officers, typically chief fiscal officers or designated officials, are pivotal in managing public pensions, ensuring documentation accuracy from enrollment to retirement. When working as intended, they act as safeguards, as pension boards lack resources to independently verify member information. Certifying Officers and their supervisors, who must undergo mandatory training on enrollments, must certify eligible employees in the pension system and report contributions quarterly to DPB.

Upon a member’s retirement, employing agencies, acting through their Certifying Officers or another designated employee, have a similarly important role. They bear primary legal responsibility for providing truthful and complete information to DPB in connection with a member’s retirement application. The Certifying Officers (or another employee designated for this purpose) must complete a form certifying service and final salary, which includes employment status and any pending disciplinary issues. To that end, the certification form requests information about the member’s reason for leaving employment—resigned, dismissed, or terminated—whether the member was suspended from employment or facing disciplinary action or indictment at the time of certification, and whether there are any pre-arrangements to return to employment. Regulations require Certifying Officers to provide DPB with any settlement agreements involving misconduct within 60 days, a step that is crucial for determining pension eligibility. Notably, there is mandatory training and supervision required by law for the enrollment and annual certification process; there is not similar training required for employees involved with providing DPB with information related to retirements.[25]

After discovering that 21 members had not received an honorable service review, OSC interviewed the Certifying Officers from the departments these members retired from to understand their role in the process that prevented DPB and the Board from fulfilling their obligations. With little exception, many Certifying Officers failed to report necessary information, often misunderstanding their role, or incorrectly assuming DPB conducts due diligence independently. Multiple Certifying Officers made statements suggesting their mistaken beliefs that their role was of limited importance, or that all state agencies’ systems are linked, and thus someone in Treasury would automatically know when a member of the public pension system was criminally charged or disciplined in a civil service jurisdiction.

The interviews revealed that most of the Certifying Officers focused almost exclusively on employment dates and final salaries when completing their certifications. Some did not appear familiar with the term “honorable service,” and failed to recognize it as essential for pension eligibility, while others recognized the term but did not provide relevant information to the Board for review. When OSC asked about reporting police disciplinary information to DPB, the consensus among the Certifying Officers was that if an employee was leaving, they would not provide information about discipline, as long as a disciplinary matter was not “pending.” However, what Certifying Officers considered to be “pending” varied. A Supervising Certifying Officer for a state agency said, “I mean, from my point of view, pending means it’s open . . . if it’s resolved, then it's not anything we would report.” When pressed further, she explained that she would not provide the information to DPB because resolved matters should not impact a member’s ability to retire.

Even if there are no pending matters, a Certifying Officer must select the most appropriate of three options related to the member’s reason for ending employment—resignation, dismissal, and termination. Yet, OSC found two instances in which the Certifying Officer selected “resignation,” which is the choice that does not indicate any issues, even though the members were being criminally prosecuted and ultimately were ordered to forfeit public employment. These separations from employment, even if by submitted letters of resignation, were hardly “voluntarily” in these instances because the criminal conduct touched their public employment, making forfeiture of public employment mandatory.[26] The Certifying Officer in one such instance said she suspected there was something unusual about the member’s resignation when she was told to hold off on certifying service and salary, but believed that inquiring further was “above [her] pay grade.”

Most Certifying Officers lacked direct access to disciplinary files, often relying on other members of the employing location, limiting their ability to report complete and accurate information. DPB described the process of receiving information from the employing locations as a “twisted game of telephone.” While Certifying Officers can face prosecution for falsifying records, DPB reported that there were no real consequences for failing to report misconduct, despite training provided by DPB. DPB emphasized that it does not have the authority to prosecute those who fail to provide information or certify to false information, which is a fourth-degree crime.[27]

Recent efforts to improve the process include updates to the certification form and advising employers to confirm pending investigations with the Chief of Police, aiming to enhance accountability and reporting accuracy. DPB has also reportedly increased the sources of information it now reviews to obtain information related to honorable service.

2. Some settlement agreements are designed to prevent full information from being shared with the Division of Pension and Benefits, the Board, or the public.

To avoid the financial and other costs associated with protracted litigation and public embarrassment, among other concerns, public employees—including law enforcement members—and their employing agencies will often choose to “settle” disciplinary matters regardless of how compelling the evidence of employee misconduct may be. No two settlements are the same, but there are a few common variations. For example, a police department may choose to enter into a contractual agreement with a police officer by which the department agrees not to impose discipline or agrees to dismiss charges against an officer, to ensure that officer will leave without costly protracted litigation or facing public scrutiny of the office, officer, or the underlying misconduct. The goal of such a settlement agreement may be to allow the employer to move on from a problem employee more quickly and replace them, while at the same time protecting the officer from a serious misconduct finding that necessarily implicates honorable service and could jeopardize their pension.

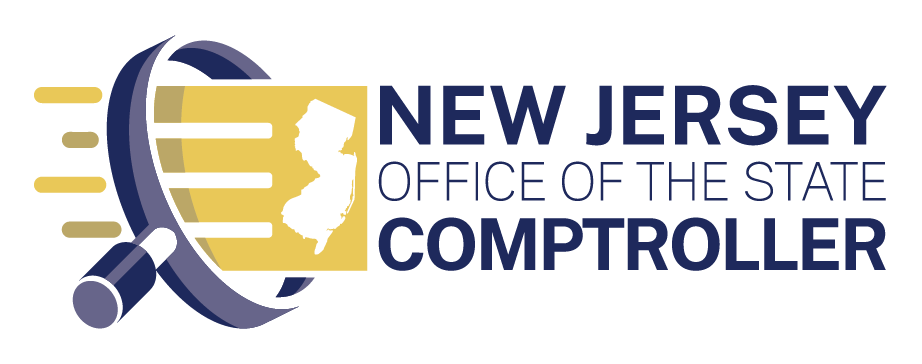

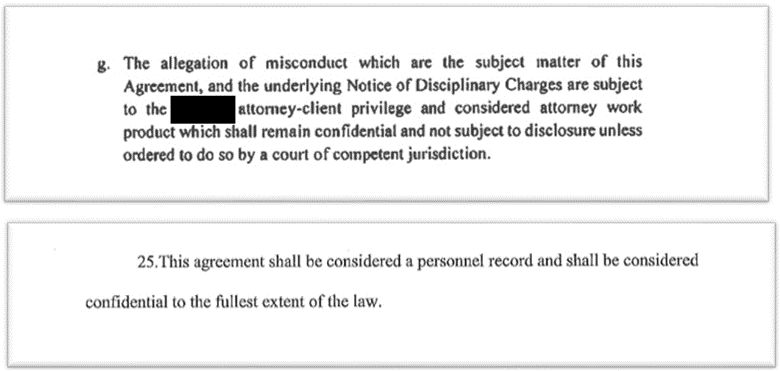

While the department and the employee may wish to keep a settlement agreement completely confidential, New Jersey law places limits on this practice and threatens penalties for noncompliance.[28] Despite this, OSC saw multiple examples of attorneys on both the employee and employer sides agreeing to terms designed to shield the settlement agreements from public or other inspection. In one egregious example, the settlement agreement explicitly designated the “allegation of misconduct” as subject to the attorney-client privilege and attorney work product protections, despite settled law that makes clear such designations would be entirely unsupportable.[29] In other settlement agreements, OSC found multiple problematic terms, including prohibited confidentiality and non-disclosure provisions[30] and an attempt to misclassify an agreement to shield it entirely from public review.[31] Some are shown below.

The law has been settled for close to two decades that that these kinds of settlement agreements must be disclosed to the pension system. DPB regulations put all public employers and employees on notice of this affirmative requirement that any employer participating in a State pension fund or retirement system shall be responsible for informing the Division of any settlement agreement.[32] This means the employer has the affirmative obligation to inform DPB of the settlement, including by providing DPB with a copy of the agreement within 60 days along with the employer certification of service and salary relative to an employee’s claim for benefits. The requirement to provide settlement agreements is also noted in both the Certifying Officer training and user-friendly “fact sheets” published by DPB and the other pension boards to make the various pension laws and regulations more accessible. As explained in more detail below, these settlement agreements provide critical information that allows the Board to conduct honorable service reviews and to perform necessary calculations related to creditable service and the ultimate pension award,[33] among other related tasks.

Yet, as noted above, there were numerous instances in which neither the Certifying Officer nor any other representative from the various employing agencies shared copies of agreements settling disciplinary charges with DPB or the Board, or even notified them of the existence of such an agreement. As a result, both DPB and the Board were unaware of the existence of at least 5 settlement agreements until OSC inquired about them.

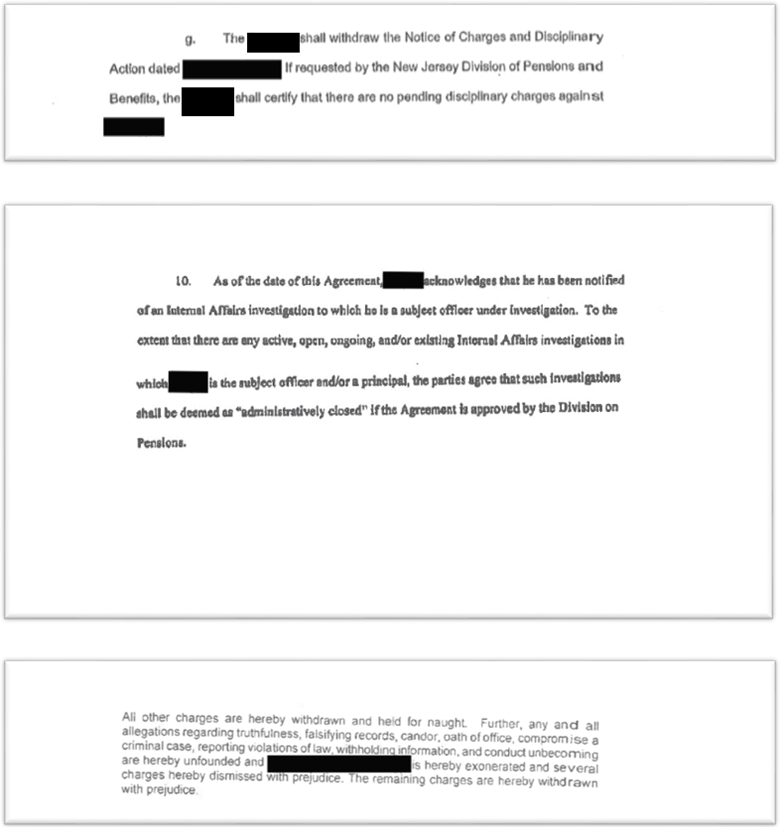

OSC also observed a trend in the settlement agreements in which the employer and employee sought to use the agreement to obscure and even alter the factual record of what had transpired, without regard to the propriety of such an agreement. In one settlement agreement, the terms of the agreement appeared to resolve the disciplinary matter against the member, essentially before it began. In that instance, the settlement agreement indicated that there was a matter that was being investigated for potential discipline to be brought against the member. However, the member was eligible for retirement in the near future, so the parties agreed it was mutually beneficial to resolve the matter and “administratively close” the discipline.[34] This agreement also did not make its way to the Board before the member’s retirement benefits were approved. OSC also observed more than one instance in which the settlement agreement was specifically crafted to avoid findings of dishonesty or lack of candor which could have broader implications for the officer.[35]

Examples of some of these practices are shown below.

Some settlement agreements re-branded and retroactively altered a member’s suspension due to misconduct as “service time” so that it would be counted toward a member’s pension.[36] The PFRSNJ statute makes clear that “creditable service for the purposes of [the] act” requires the member to have performed actual service that was “rendered” as a police officer.[37] OSC also observed that PFRSNJ was knowingly choosing to accept months and even years when a member was not merely out of work, but not permitted to work due to their misconduct, as time that counted toward qualifying for their pension in the first instance and increasing their monthly compensation upon retirement. This was the case in several instances described below, as well as in a settlement agreement highlighted by the Attorney General in a public investigative report issued in November 2023.[38]

Other settlements seemed to permit members who were supposedly serving discipline and not permitted to work to continue to accrue service credit toward their pension by using vacation, sick, or other accrued time.[39] In one instance, the employer permitted the member to use accrued vacation time back to the date of her suspension, allowing her to reach 25 years of service credit and qualify for the more lucrative special retirement. The terms of the settlement agreement credited her with service time when she was otherwise “unfit for duty” and allowed her to resign in good standing.

In yet another instance, the member was permitted to use “terminal leave” to reach 25 years of service credit and qualify for special retirement, despite the member being demoted due his misconduct. Rather than being terminated, the settlement agreement allowed the member to accrue pensionable service for time while not actually performing a service. Some settlement agreements even contemplate that the Board may determine the member lacks sufficient service time to retire, and if so, permit the member to remain on the payroll to accrue additional service time, but not to conduct any law enforcement work.

While there is a PFRSNJ regulation intended to prevent padding of a member’s base salary with extra compensation to avoid inflated pension benefit calculations, there are no statutes or regulations specifically limiting the ability of employers and employees to enter into settlement agreements that will retroactively provide “pensionable credit” in addition to back pay for months and years when the employee was not actually working or award service credit when the member was not permitted to work, regardless of circumstances. When DPB is unaware of these settlement agreements, it is deprived of the opportunity to adjust the credit award when warranted. DPB emphasized that it is not bound by these settlement agreements and will sometimes advise members when a settlement is not in compliance with the law. The financial impact to the system, in addition to other costs of this gamesmanship, are described more fully below.

3. Other weaknesses in the retirement process undermine DPB and the Board’s ability to obtain accurate information, which are exacerbated by a lack of required self-reporting.

The above findings highlight that the processes put in place by DPB and the Board, along with a limited amount of additional scrutiny provided by PFAU when requested, have been insufficient to prevent fraud, waste, and abuse in the public pension system, at least as it pertains to law enforcement.

DPB told OSC that the processes and trainings in place to assist Certifying Officers in supplying necessary information regarding officer misconduct are robust and should be sufficient. However, in interviewing the Certifying Officers, this assumption was mistaken. While DPB makes online training modules related to the retirement process available, many Certifying Officers reported that they were voluntary and had elected not to review them, instead relying upon training provided by their predecessors or other local employees. For this reason, DPB’s trainings and policies are not being uniformly followed and have not been effective in preventing matters from falling through the cracks.

Compounding the problem, there is also a widely held misconception among the Certifying Officers interviewed that DPB automatically knows all relevant information about retiring members, regardless of whether an employer has affirmatively provided that information to them. For example, some Certifying Officers shared with OSC their understanding that DPB would automatically have access to information about criminal matters related to the member or discipline imposed. This was not the case in the 21 matters that did not initially receive honorable service reviews when they should have.

As discussed above, DPB relies heavily on Certifying Officers and other representatives from employing locations to provide them with information it needs, including the information it passes along to the relevant pension fund to conduct honorable service reviews. DPB does not have its own investigators and relies primarily on “self-identification” for honorable-service-related issues—for example, a member or employing location reporting misconduct. But in the absence of this information,[40] DPB will likely remain unaware of the misconduct. OSC found news reporting, sometimes extensive, and information included in the Attorney General’s major discipline reports, went unnoticed by DPB for years. The mere fact the information was readily available on an official government or other public website was insufficient for DPB to consider it or follow up on it.

During OSC’s investigation, DPB advised that it is now using a newer certification of service and final salary form than was used in the 21 cases that previously evaded review. DPB informed OSC that it sent out a notice to employers in addition to posting the trainings on its website. DPB also emphasized that employers are asked to review an “Acknowledgement of Terms and Conditions of Retirement” form each time a service and final salary certification is submitted to DPB. It is unknown whether the new form will increase accurate reporting, though it seeks more detailed information from the employer than the previous form.

In evaluating the weaknesses in the processes noted above, OSC sought to better understand the role played by PFAU, a small unit within the Department of the Treasury created in 2013 by Executive Order (EO) to investigate pension fraud and abuse. OSC found that PFAU’s limited role in collecting information related to honorable reviews sheds light on some of the reasons it is unable to fill in all the gaps when an employing agency does not affirmatively or voluntarily provide the necessary information. PFAU will investigate matters referred to it by DPB, or by PFRSNJ upon request, but it does not have the authority to compel law enforcement agencies to comply with its requests. While the EO requires agencies to cooperate with any requests, PFAU notes it neither has subpoena authority nor access to internal affairs files by the plain terms of the IAPP in the same way DPB does. For this reason, there are times when PFAU has struggled to obtain the necessary information without cooperation from the law enforcement agencies, which can be lacking. PFAU also reported to OSC that it lacks sufficient staffing and resources to investigate honorable service matters across multiple pension systems, particularly given its multiple other responsibilities. In terms of honorable-service-related investigations, PFAU advised OSC that those are few and far between for the unit.[41]

While OSC agrees that subpoena power would be helpful to PFAU in fulfilling its mandate, it is notable that subpoena power does not in itself guarantee cooperation. DPB and the Board, both of which have more clearly defined authority to obtain and review internal affairs files, reported varying degrees of cooperation from various employing law enforcement agencies when requesting these materials.

Since OSC’s investigation began, DPB and the Board have made certain changes to address the identified weaknesses in the system, beyond updating the certification form as noted above. DPB reported there was a meeting with the Police Chiefs’ Association about the need to share information about law enforcement discipline and informed OSC that it has a dedicated email address where departments and agencies can report misconduct. PFRSNJ reported that while it does have subpoena authority,[42] at the time it lacked the personnel to investigate all the matters that required it. PFRSNJ explained, however, that it was in the process of building out its own investigative unit. The Board adopted a resolution in May 2025 authorizing its staff to conduct initial evaluations of retirement applications that contain documentation calling into question a member’s honorable service.

While steps have recently been taken by these agencies to address some of these problems and deficiencies since OSC initiated its investigation, it remains to be seen if the changes made to date or those that are in the process of being made will remedy all of the problems identified.[43] It is also unclear just how many of these matters have already fallen through the cracks prior to these changes being implemented and what will be done by these agencies to capture and correct them now.[44]

Finally, there is currently no requirement that a member, upon retiring, must notify DPB or the Board about their prior disciplinary history, even though such a requirement could alleviate most of the above-noted concerns. A retiring public employee is in the best position to have accurate, first-hand knowledge about any misconduct during their career in public service, whether they were criminally or administratively charged, suspended, or entered into an agreement to settle disciplinary charges. Yet, when a member elects to submit a retirement application, they are not required to disclose anything about their disciplinary history except in very narrow circumstances that can be easily worked around. This is true even if the misconduct resulted in the retiring member being required to resign to resolve criminal charges, if a criminal investigation is ongoing, or if they have been barred from future public employment.

Given that honorable service is a pre-condition to receive a public pension, it would be reasonable to require a public employee to truthfully fill out a form that would, at the very least, indicate whether there was an end-of-career settlement agreement, if the employee was ever suspended for more than a certain number of days, was forced to resign or retire as a result of a criminal conviction or admission into a pretrial criminal diversionary program, or if the member is aware that they are the subject of any ongoing investigation.[45] But no such requirement currently exists.

B. Even when the Board was provided with full information about a member’s disciplinary history, aspects of the Board’s decision-making appeared inconsistent or illogical.

As set forth above, the Board is at times deprived of the complete and accurate information it needs to assess whether an honorable service review is necessary in the first instance and to consider whether any forfeiture of pension benefits would be appropriate. But whether the Board obtained information on the outset, or at some point later as in those instances mentioned above, OSC found aspects of the Board’s decision-making in its honorable service and forfeiture analyses to be inconsistent or illogical in one or more significant ways.

For example, there were many instances across the almost 60 matters that OSC reviewed in which the Board heavily weighed the mere fact that a member was permitted to resign in so-called “good standing” as part of a settlement agreement to justify not forfeiting any part of the member’s pension. While the term “good standing” in this context suggests the member’s conduct must have been good or at least on good terms prior to retirement, the reality is much the opposite. Members permitted to retire in “good standing” as part of settlement agreements reviewed by OSC include those who, among other things:

• obstructed and interfered in criminal investigations for personal benefit;

• sent unwanted sexually explicit messages to a female victim;

• repeatedly punched an arrestee after he was handcuffed;

• posted racist messages on social media; or

• were repeatedly suspended for unrelated instances of misconduct.

In many cases, these members were suspended, demoted, and even terminated prior to signing an agreement, and the settlement agreement strongly implied that one of the reasons the good standing designation was permitted was because the member’s resignation was going to be irrevocable. Notably, Civil Service Commission regulations’ definition of “good standing” is based solely on the notice period given by the employee before leaving, without regard to the employee's conduct. It thus seems inconsistent that the Board would choose to consider a resignation in “good standing” a weighty factor in favor of not forfeiting any portion of a member’s pension when they conducted themselves dishonorably.

Some members who engaged in misconduct that rose to the level of criminality inexplicably fared better before the Board than members whose misconduct was handled solely on an administrative level. For example, one member was criminally charged with theft of time that occurred over a year-and-a-half period. Rather than face jail time, the member was given the opportunity to be diverted away from the criminal justice system and enter the pretrial intervention program (PTI). The PTI paperwork made clear the member’s admission into the PTI program was conditioned upon his retirement.[46] The paperwork also noted the member owed thousands in restitution to the employing municipal police department, which was “expected to be satisfied through separation of service.”

Notably, the member was initially placed on unpaid leave pending the outcome of the criminal process. However, with a written agreement, the member was quickly returned to paid status after explicitly agreeing to pay back all salary paid during this time if, ultimately, he was required to give up or forfeit his job because of the criminal process. In other words, for close to a year, the member continued to take home his full salary, which was well over $100,000, while he was not working. Significantly, the agreement did not require the member to use any accrued time while remaining on paid status in the interim. As part of a settlement agreement with the municipality immediately prior to retiring but before he completed PTI, the member was allowed to pay back the time stolen using a portion of his accrued paid time off rather than having to pay cash out of pocket. The agreement was silent on the salary the member was paid while not working but noted that all claims would now be resolved.

When the Board conducted its honorable service review, it found the member’s misconduct directly related to his public duties, but of moderate moral turpitude because of his personal gain. The Board nonetheless determined that no forfeiture of pension benefits was warranted following a review of the documentation it was provided. Considering the “availability and adequacy of other penal sanctions,” the Board noted that the member was entered in the PTI program with conditions, including separation of service from his employer. The Board also noted that the member did not plead guilty to enter PTI and that upon its completion, the administrative charges would be dismissed.

In essence, the member was able to avoid suffering any criminal consequences for his actions and avoided the administrative process altogether. He was allowed to resign even though the administrative charges would only be dismissed upon completion of PTI, which did not happen before the resignation. Worse still, in addition to being approved for a full pension with no penalty, the member kept the six-figure salary to which he had previously agreed he would give back since he did not work and was forced to give up his job. Compounding the issue, he was also granted an extra unearned year of service time by the Board, thereby guarantying him an undeserved higher pension payment for life. And he walked away with the remainder of his accrued paid time off, which was over $20,000. In sum, the notion that pension forfeiture was somehow inappropriate due to the “availability and adequacy of other penal sanctions” was entirely unsupported in this instance.

OSC observed that even in cases in which the Board decided that a partial forfeiture of benefits was a suitable penalty for criminal acts committed by members, in assessing the appropriate penalty for such acts, the Board took deliberate actions to ensure the penalties were minimal and the members still qualified for a “special retirement” with a higher pension. This occurred with two members who were ordered to forfeit their public office: one who pleaded guilty to assaulting a handcuffed resident at a juvenile justice facility, and another who pleaded guilty to forgery for submitting fake overtime slips to report more hours than worked or for road jobs that never existed.

The Board also took deliberate steps in calculating appropriate partial forfeiture to protect members’ eligibility for a service retirement by opting to forfeit their salary only and not any service credit, even when the conduct was repeated or pervasive. In one case, the Board justified its decision to forfeit salary instead of service by expressing concern that it would be “too severe” to revoke a member’s service time back to the first of multiple incidents when he assaulted his spouse over a four-year period, causing serious injuries like broken ribs and a broken nose, along with other misconduct. The Board noted that forfeiting the member’s service time would have rendered him ineligible for a service retirement.

There were also inconsistencies in the Board’s conclusion when different members had similar misconduct. For example, there were three incidents in which a member had been charged with driving while intoxicated that ultimately resulted in partial forfeiture of their pension benefits. In all three of these matters, the Board found a high degree of guilt and culpability associated with the member’s conduct. However, in only one, the Board found that the conduct related to the member’s employment. All three incidents occurred while the members were off duty, not in uniform, and did not involve police vehicles. All three involved severe, dangerous conduct in addition to driving while intoxicated—speeding and eluding, driving the wrong way on a major roadway, and assault by auto. The Board noted in all three matters that police officers are held to a “higher standard” as they are “sworn to uphold the law” and should be a “role model” for the community. There was nothing in the record to indicate why the Board found that the members’ conduct was not related to their “public duties” in two of these cases but was related in the third.

The Board also consistently treated member misconduct related to dishonesty and lack of candor as offenses involving low moral turpitude and thus less deserving of penalty. Considering state and federal case law and directives in New Jersey addressing the significance of truthfulness to being a law enforcement officer, this trend in the Board’s decisions appeared surprisingly dismissive.[47] New Jersey courts have found that for police officers, truthfulness is an “essential trait.”[48] The qualifications required to hold a position such as a police officer require a “high level of honesty, integrity, sensitivity and fairness in dealing with members of the public, knowledge of the law, and a pattern and exhibition of law-abiding conduct.”[49] Police officers are “constantly called upon to exercise tact, restraint and good judgment in [their] relationship with the public” and “must present an image of personal integrity and dependability in order to have the respect of the public.”[50] Police officers are held to a higher standard as “one of the obligations [they] undertake[] upon voluntary entry into the public service.”[51]

In multiple matters, the Board acknowledged that the internal investigation revealed that officers had been untruthful, knowingly made false statements during investigations, and even falsified records or reports, but the Board considered these actions to be of low moral turpitude and not warranting any pension forfeiture. This included an instance in which a member made several false statements during an internal investigation related to an improper release of an arrested individual, who had assaulted other officers, among other offenses. In another example, a member was found to have purposely omitted information from his report about an incident, made various untruthful statements to internal affairs, and falsely reported that he was assaulted by an arrestee first, which was disproven by video evidence—and yet the Board determined the quality of guilt and moral turpitude to be low and decided not to forfeit any portion of the member’s benefit. In the few instances in which the Board found a member’s actions that involved some dishonesty or fraud to be of moderate or high moral turpitude, and requiring some small amount of partial forfeiture, there were criminal charges involved.

The Board was also contradictory at times in its approach to whether it would conduct an independent assessment of evidence. There were two instances in which the Board independently reviewed evidence it received to evaluate whether it agreed with the ultimate findings, in one case even reviewing video evidence to come to a different conclusion than the internal affairs investigators about the severity of an assault. In stark contrast, there was another instance in which the Board was willing to rely solely on the superficial information set forth in the Attorney General’s Major Discipline reporting to determine whether pension forfeiture was warranted. In multiple instances, the Board was satisfied with resolution through settlement agreements with no consideration of the facts of the misconduct. As set forth below, unreasoned decisions can result in costly and enduring ramifications for the pension system.

C. OSC found significant costs of unreported misconduct and a broken system.

The weaknesses OSC uncovered through this investigation of the retirement and pension review process have had and will continue to have significant costs to the pension system that are both non-monetary and monetary. The public pension system is funded by member contributions, but it is also funded by significant contributions from the State to ensure it can be sustained. In fiscal year 2023 alone, the State contributed over $600 million in public funds to PFRSNJ.

Even with this significant contribution, the State still has an unfunded PRFSNJ pension liability of over $4.4 billion. Given this substantial unfunded liability, it remains critically important that board members safeguard existing pension funds, ensuring they are only paid out to deserving members who meet the eligibility criteria.

1. There are significant non-monetary costs and consequences to the fund, the members, and the public when full pension benefits are awarded regardless of serious misconduct.

The non-monetary costs and consequences associated with allowing members who have committed serious misconduct to go unchecked into retirement cannot be overstated. First, as discussed above, the purposes of providing a pension to public employees include incentivizing commitment to public service and attracting and retaining public employees who are committed to serving their communities honorably. When the system breaks down and misconduct goes under-reported to the Board, the incentive for police officers to conduct themselves in a manner deserving of such a valuable, taxpayer-funded benefit is lost. If officers observe that even the most egregious misconduct often does not reach the Board or result in any reduction of pension benefits, the deterrent value of an honorable service review deteriorates.

Trust between law enforcement and the communities they serve is also eroded when serious misconduct is rewarded so handsomely. As discussed above, police officers are held to a higher standard due to their position as role models in the community. When the Board’s decisions do not accurately reflect whether the service they rendered was in reality honorable, it undermines the public’s trust in the system as whole.

The Board is also the fiduciary of the pension fund and by forfeiting the pension rights of those members who have committed serious misconduct, it can prevent misuse of pension funds and protect the retirement benefits of deserving public employees. When that does not occur, the investment of deserving members in their retirement cannot be properly protected and member faith in the pension system declines. Public servants devote substantial parts of their careers to public service, contributing to and earning their pension benefits over time. A pension is their reward for that service and should not be used by employers to pass along the costs of problem employees to the state pension system.

2. The financial costs to the pension fund are high when the Board lacks necessary information to decide on service reviews, grants unwarranted retirements, or makes inconsistent decisions about forfeiting service or salary.

Some of the Board’s exercises of discretion throughout this process may appear inconsequential. But when projected over the member’s lifetime, they can result in hundreds of thousands of dollars in additional liabilities to the fund. In the aggregate, these costs are exponentially higher.

For example, when the Board grants the more lucrative special retirement versus service retirement to undeserving members, those decisions come at a high cost to the pension fund. “Special” retirement, which requires a member obtain 25 years of creditable service under PFRSNJ, is far more lucrative than the non-age based “service” retirement, which only requires a member to serve as a law enforcement officer for 20 years.[52] While service retirement allows PFRSNJ members to receive 50 percent of the salary used to calculate their benefit, special retirement allows members to receive 65 percent of the same.[53]

The financial impact of DPB’s calculations of the creditable service[54] or the Board decisions allowing or ensuring that members—even those that have committed serious misconduct—reach 25 years or more of creditable service can have a detrimental financial impact on the fund over time. As discussed above, OSC found instances of members receiving creditable service through settlement agreements for the sole purpose of permitting the member to reach 25 years of creditable service, and instances where the Board purposefully calculated forfeiture to allow members to retain special retirement privileges. In turn, those members were eligible to apply for and receive the more lucrative special retirement. By allowing this to happen, the Board exposes the fund to a lifelong liability for members who were less-than deserving.

Below is a table illustrating the difference between service and special retirement benefits in a hypothetical example where compensation to calculate benefits was $100,000, and the misconduct occurred when the member had 23 years of service credit. This hypothetical also assumes a life expectancy for the member of 75 years and does not consider other costs such as retired health benefits or possible survivor benefits.[55]

Figure 1: Hypothetical — Differences Between Service and Special Retirement Benefits

|

|

Special Retirement |

Service Retirement |

|

Final Salary |

$100,000 |

$100,000 |

|

Years of Service |

25 |

23 |

|

Annual Benefit |

$65,000 |

$50,000 |

|

Monthly Benefit |

$5,417 |

$4,167 |

|

Retired at Age 50, |

$1,625,000 |

$1,250,000 |

|

Lifetime Benefit Difference |

– |

$375,000 |

The Board’s decision whether to impose partial forfeiture and whether to reduce benefits based on salary, service, or both, also impacts the fund. The monetary impact of the Board’s decision not to impose any forfeiture of a member’s benefits can have a significant impact in the amount of money dispersed by the fund over a member’s lifetime. Beyond the forfeiture of service credit mentioned above, which could determine a member’s eligibility for a higher percentage of final compensation used to calculate benefit, if the Board can deem that some amount of forfeiture is warranted on balance, it can exercise its discretion regarding the amount of reduction in benefits. Generally, with partial forfeiture, a member’s benefits will be calculated as if the accrual of pension service terminated as of the date of the member’s misconduct. But if the Board finds that calculation renders a result that is unreasonable or unjust, it can deviate from that standard and use alternative calculations.

As discussed above, OSC found instances in which the Board deviated from the standard partial forfeiture calculation, when it determined in its discretion that the penalty would be too harsh, often times choosing to forfeit salary only, or a percentage of the member’s dishonorable service in proportion to their career length. In many of those instances, the Board’s goal was to secure a member’s eligibility to a certain type of retirement. Again, those kinds of decisions are non-negligible and, in the aggregate, can come at great cost to the pension system as a whole.

In the hypotheticals illustrated below, the member’s final salary was $102,000, the salary when misconduct first occurred three years prior to retirement was $100,000 and those three years between when misconduct first occurred and retirement represent 12 percent of the member’s 25 year career and are considered to be dishonorable. As above, this hypothetical assumes a life expectancy for the member of 75 years.

Figure 2: Hypothetical — Comparing Certain Pension Forfeiture Possibilities

|

|

Honorable Service |

Forfeiture of Salary |

Forfeiture of Time Considered to be Dishonorable |

|

Final Salary |

$102,000 |

$100,000 |

$89,760 |

|

Years of Service |

25 |

25 |

25 |

|

Annual Benefit |

$66,300 |

$65,000 |

$58,344 |

|

Reduction in Annual Benefit |

– |

$1,300 |

$7,956 |

|

Monthly Benefit |

$5,525 |

$5,417 |

$4,862 |

|

Reduction in Monthly Benefit |

– |

$108 |

$663 |

|

Retired at Age 50, |

$1,657,500 |

$1,625,000 |

$1,458,600 |

|

Lifetime Benefit Difference |

– |

$32,500 |

$198,900 |

As discussed above, OSC identified its sample from publicly available information. OSC has not reviewed on a larger scale how many members have received full pension or have had partial forfeiture calculated to allow for eligibility of higher benefits despite having committed serious misconduct. Nonetheless, within the sample that OSC reviewed there were concerning trends. If misconduct or settlements agreements are not revealed to DPB for proper calculation of service credit and in turn inaccurate or incomplete information is factoring into the Board’s decision, or if the Board chooses to honor credible service negotiated through settlement agreements, it will stress the financial integrity of the pension fund overall.

Recommendations

In light of its findings, OSC makes the following 15 recommendations, in addition to making referrals, where appropriate, to the Office of Attorney Ethics and the Office of the Attorney General.

DPB and PFRSNJ should consider amending their respective regulations to:

-

Explicitly require that the employing location proactively identify any information related to honorable service and provide access to the relevant records for each member. At this time, DPB’s Honorable Service “fact sheet”[56] provides a comprehensive list of documents required in cases of misconduct, which are pursued administratively and criminally. But the fact sheet is merely a guidance document and does not have the same legal effect as a statute or regulation.

-

Require members to self-report disciplinary information for the entire period they were enrolled in the public pension system when the member applies for retirement. This could include requiring that the member certify with their application for retirement whether they have been the subject of any administrative or internal affairs investigation, criminal prosecution, or civil matter, or have served a suspension for any amount of time that resulted in a settlement agreement. Members, who have firsthand knowledge of their own circumstances, are in the best position to provide the Board with accurate information. This requirement would encourage members to serve honorably, knowing they must self-report any misconduct.

-

Conduct internal audits to determine whether members with serious misconduct—beyond those matters already identified by OSC—have been able to evade honorable service reviews and, in turn, the Board should reopen matters for those reviews, as necessary to determine whether any forfeiture of benefits should be imposed against the member.[57]

-

Clarify when creditable service may be granted to members, similar to N.J.A.C. 17:4-4.1 regarding creditable compensation, and expressly prohibit the use of vacation, sick leave, or other paid time off as creditable service during a period of suspension for misconduct or during a period of time when the member would no longer be permitted to work as a law enforcement officer.

Beyond amending its regulations, PFRSNJ should consider:

-

Conducting a brief review of publicly available information about each retiring member, including a search for major discipline and news reporting to help ensure that the Board is aware of relevant information regarding honorable service.

-

Adopting written policies and procedures that govern the Board’s decision-making process to ensure consistency in its decisions, fairness to the members, and to improve public confidence in the system as a whole. This should include:

• Designating offenses or categories of offenses that are considered by the Board to be of low, moderate, or high moral turpitude;

• Setting forth parameters that inform any decision to deviate from the typical amount of partial forfeiture (back to the date of the misconduct), to ensure consistency and fairness to members who commit similar misconduct and to the system as whole;

• Standardizing the materials the Board will request and consider in each matter, including whether the Board will review the entire internal affairs file (including any media), if applicable; and

• Tracking the Board’s decisions over time to ensure that similarly situated members are receiving similar outcomes.[58]

Employing locations should consider:

-

Whether their current Certifying Officers and Supervising Certifying Officers have adequate access to disciplinary information for law enforcement employees to be able to accurately fill out the certification of service and final salary. To the extent a civilian employee is unable to access internal affairs files, and thus cannot certify based on firsthand knowledge, the employing location should consider affirmatively designating a second Certifying Officer within the law enforcement agency. This will allow for coordination with the civilian employee and ensure that the law enforcement employee is required to certify to the accuracy of the information as well.

-

Mandating training for their Certifying Officers and Supervising Certifying Officers, as well as any employee assisting with pension-related certifications.

- Putting procedures in place to ensure that complete settlement agreements are provided to the Certifying Officers, DPB, and the Board.

The Legislature should consider:

-

Reviewing and expanding the list of offenses that result in mandatory forfeiture of pension benefits to include convictions for certain offenses covered under N.J.S.A. 2C:24-4, endangering the welfare of a child, for example, and to ensure that substantially similar federal and out-of-state convictions for offenses like perjury are captured by the law.

-

Requiring members of PFRSNJ and other state pension funds to self-report disciplinary information to the relevant pension board that oversees them. In doing so, the Legislature should consider imposing consequences on any member found to have intentionally failed to disclose required information or who was intentionally untruthful or misleading regarding their application for retirement.

-

Prohibiting employers from accepting resignations in “good standing” from retiring employees who the employer would not permit to continue working in a law enforcement capacity, whether because of an ongoing criminal matter, or because the member was admitted into PTI, among other reasons.

-

Requiring employers to adhere to formalities similar to those set forth in Chapter 52 for Annual Membership Certification, including mandating training for all employees of employing locations who are authorized to report information to the pension systems, along with granting DPB or the pension boards’ authority to assess penalties against any non-compliant employers.

-

Providing the Attorney General with the authority to periodically audit settlement agreements entered into by PFRSNJ members and their employing law enforcement agencies. As Chief Law Enforcement Officer, the Attorney General should have the power to ensure, among other things, that administrative investigations, charges, and findings related to officer untruthfulness are not being withdrawn or dismissed as part of these agreements when there was sufficient evidence to prove the allegations due to discovery obligations in criminal cases.

-

Closing the loophole that permits a member to circumvent the deferred retirement statute, N.J.S.A. 43:16A-11.2, by “resigning” from employment immediately prior to pleading guilty to a crime that directly related to the member’s public employment. OSC observed one instance in the sample reviewed where an employer dropped administrative charges for serious misconduct to allow the member to resign in so-called good standing, almost immediately prior to them pleading guilty to a crime. This ensured the member, whose crime was found by the Board to relate to the member’s employment as a law enforcement officer, could say they were not technically “remov[ed] for cause on charges of misconduct or delinquency,” and were thus able to receive deferred retirement benefits.

[1] Geller v. Dep't of Treasury, Div. of Pensions & Annuity Fund, 53 N.J. 591, 597 (1969).

[2] Ibid. Our “public pension systems are bound up in the public interest and provide public employees significant rights which are deserving of conscientious protection.” Zigmont v. Bd. of Trs., Teachers’ Pension & Annuity Fund, 91 N.J. 580, 583 (1983). Because pension statutes are remedial in character, they are liberally construed and administered in favor of the persons intended to be benefited thereby. Klumb v. Bd. of Educ. of Manalapan-Englishtown Reg'l High Sch. Dist., Monmouth Cnty., 199 N.J. 14, 34 (2009).

[3] Beyond administering multiple state pension systems, DPB is also responsible for managing the State Health Benefit Plan, among its other responsibilities.

[4] N.J.S.A 43:16A-5.

[5] “An inappropriate allowance of benefits tends ‘to place a greater strain on the financial integrity of the fund in question and its future availability for those persons who are truly eligible for such benefits.’” Cardinale v. Bd. of Trs., 458 N.J. Super. 260, 272 (App. Div. 2019)(quoting Francois v. Bd. of Trs., 415 N.J. Super. 335, 350 (App. Div. 2010) (internal quotations omitted). “[E]ligibility is not to be liberally permitted.” Smith v. State, Dep't of Treasury, Div. of Pensions & Benefits, 390 N.J. Super. 209, 213 (App. Div. 2007).

[6] See State v. Anderson, 248 N.J. 53, 71-72 (2021) (quoting N.J.S.A. 43:1-3(a)); see also Uricoli v. Bd. of Trs., Police & Firemen’s Ret. Sys., 91 N.J. 62, 66 (1982) (“[H]onorable service is an implicit requirement of every public pension statute.”); N.J.S.A. 43:3C-9.5(d) (explicitly noting that the “non-forfeitable right” to receive pension benefits “shall not be construed to preclude forfeiture, suspension or reduction in benefits for dishonorable service”).

[7] Pension board minutes and decisions are subject to the Open Public Meetings Act. N.J.S.A. 10:4-6 to -21.

[8] See N.J.S.A. 43:1-3.1.

[9] See N.J.S.A. 43:1-3.1(a). But see State v. Nucera, No. A-4605-91 (App. Div. Dec. 31, 2024) (slip op. at 33-34) (finding that the federal offense of perjury under 18 U.S.C. § 1001(a)(2) was not substantially similar to the state crime of perjury under N.J.S.A. 2C:28-1 and reversing mandatory forfeiture of pension benefits for the member).

[10] See N.J.A.C. 17:1–6.1.

[11] Assuming that the pension board is appropriately informed of the misconduct, the Uricoli factors “must be balanced and then weighed in terms of the goals to be achieved under the pension laws.” Uricoli, 91 N.J. at 78. The pension board may attribute more weight to factors seven, eight, and nine, when applicable. See Corvelli v. Bd. of Trs., 130 N.J. at 539, 552-53 (1992). In addition, N.J.S.A. 43:3-1 provides for forfeiture of pension upon conviction of certain crimes.

[12] New Jersey Division of Pensions and Benefits, Honorable Service at 3 (Honorable Service Factsheet) (Mar. 2019), fact76.pdf (state.nj.us).