An Investigation of Irvington’s Mismanagement of Opioid Settlement Funds

Table of Contents

- Posted on - 07/8/2025

- Executive Summary

- Background

- Methodology

- Findings

- State Oversight of Local Opioid Settlement Spending is Inadequate

- Recommendations

Executive Summary

The opioid epidemic has devastated communities across the nation, including in New Jersey, causing immense suffering and loss. Over the past two decades, opioid addiction has overwhelmed public health systems, strained community resources, and created an urgent need for meaningful intervention and support. In response, New Jersey and many of its local governments initiated lawsuits and negotiated settlements with pharmaceutical manufacturers and distributors, aiming to provide financial resources to help affected communities. These opioid settlement funds—totaling over $1 billion and counting—are intended to support prevention, treatment, and recovery initiatives for opioid addiction.

The Township of Irvington (Irvington or the Township) is one of many municipalities receiving a share of these funds—money intended to combat a deadly public health crisis. Irvington is responsible for ensuring the funds are used in compliance with state law and the settlement terms. The Office of State Comptroller (OSC), which has been designated by the Legislature to coordinate with the Department of Human Services (DHS) and the Office of the Attorney General (OAG) to ensure opioid funds are spent appropriately by local governments, investigated whether the Township has satisfied these duties and found it failed to do so in multiple ways:

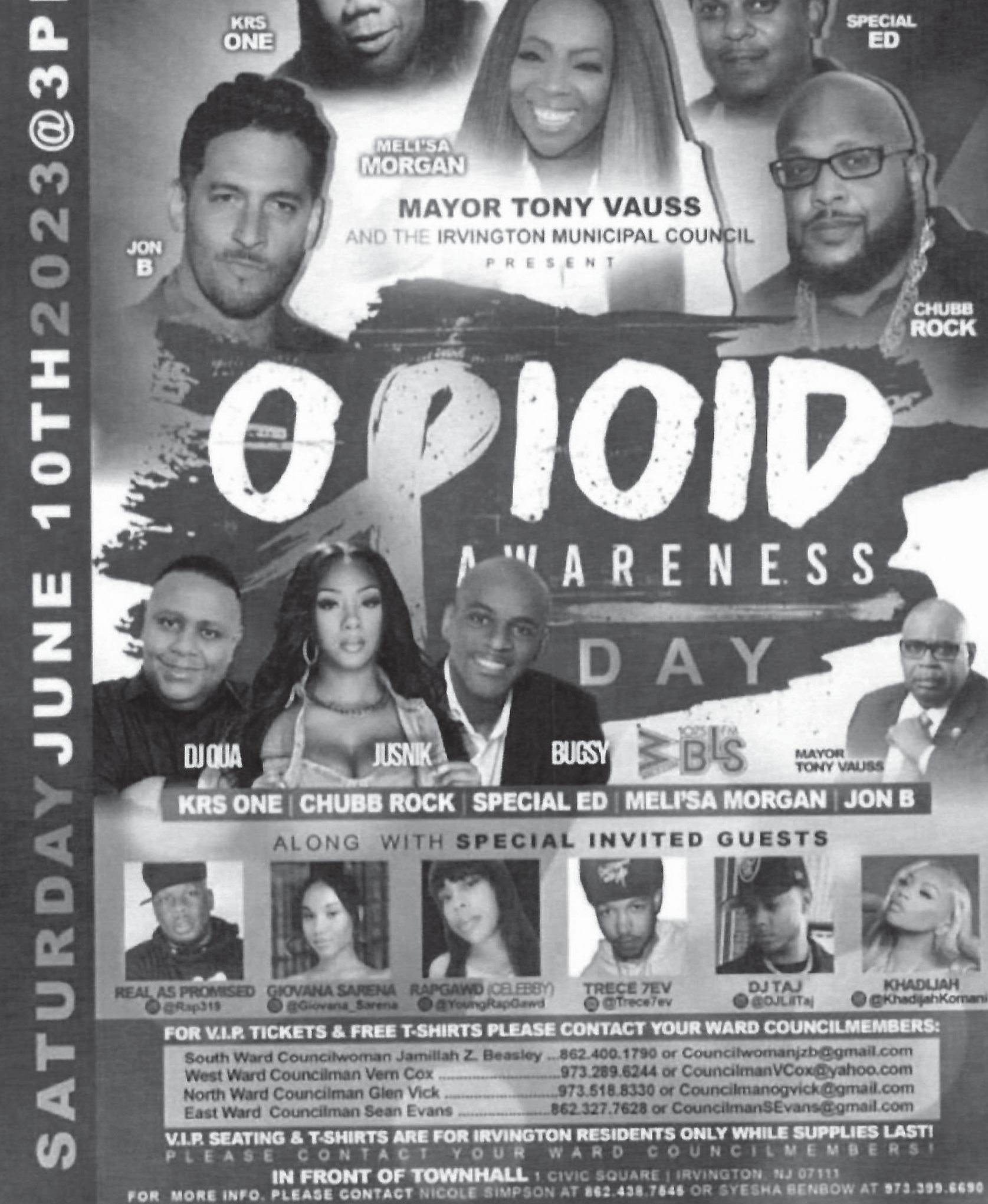

- The Township wasted and misspent over $632,000 on two “Opioid Awareness Day” concerts in 2023 and 2024. The Township spent exorbitantly to promote and hold events featuring numerous musical performers, multiple DJs, and prominent billing for Irvington Mayor Tony Vauss.

- The decision to spend opioid funding on concerts was made by the Mayor and other high-level Township officials without consulting Irvington residents or public health experts. Neither Irvington’s Director of Health and Senior Services nor its Director of Public Safety, who are on the front lines of responding to the opioid crisis, were consulted. Although the Township was required to spend its opioid funds in an evidence-based or evidence-informed manner, it allocated these funds to concerts without relying on any objective evidence that such large expenditures would help address the public health crisis.

- A substantial portion of the opioid funds--$368,500—was paid to a Township employee, Antoine Richardson, who was hired to secure musical performers for the event. Township officials do not know—and never asked—how Richardson actually spent the hundreds of thousands of dollars he received. In interviews with OSC, Richardson’s wife refused to account for the money, while Richardson claimed not to know or recall how the money was spent.

- The Township spent over $200,000 on billboards and other promotional materials advertising the events, including $16,000 for mobile billboards prominently featuring Mayor Vauss and $34,445 on t-shirts. None of the billboards, promotional materials, or t-shirts that Irvington provided to OSC included information about obtaining treatment or avoiding abuse of opioids—they simply promoted the concerts. The Township also used opioid funds to pay nearly $13,000 to rent luxury trailers for the performers, and $29,000 to purchase generators and food supplies like popcorn machines, cotton candy machines, and shaved ice.

- The substantial funding expended by the Township on the concerts was wasted because the events did little to promote opioid awareness or provide opioid-related services to people dealing with opioid addiction. Relative to the funds spent, only a superficial effort was made to raise awareness through, for instance, short speeches from the stage. The Township also invited service providers to interact with members of the public and share resources and Narcan at the concert, but these were afterthoughts and could have happened at any community event, without wasting hundreds of thousands of dollars on musical guests, luxury trailers, and popcorn machines. And the Township notably requested a donation of Narcan, without using any of its opioid funds, even though this life-saving drug was the only clearly effective measure at one of the concerts that could directly address the crisis and potentially save lives.

Public entities entrusted with opioid funds have a legal and ethical obligation to spend them transparently and responsibly. These funds are meant to address an ongoing public health emergency that continues to claim lives. When municipalities like Irvington fail to meet that duty, they not only waste resources but erode public trust and betray the communities most in need of support.

Irvington’s conduct shows that the State must do more to ensure the opioid settlement funds are used for their intended purpose. State law designates the DHS as the lead agency for ensuring appropriate use of opioid funds, but DHS claims to have no oversight role involving local governments beyond collecting annual reports. It does not provide guidance to local governments on evidence-based or evidence-informed spending—despite having the expertise and institutional resources to do so. This undermines the intent of the settlements.

In conducting this investigation, OSC also uncovered that Richardson holds what is effectively a low-show job—a government position that offers a full-time public salary and benefits for part-time work—while at the same time collecting six-figure vendor payments from the Township. He is officially employed by Irvington under the misapplied civil service title “Keyboarding Clerk I,” though his only job duty is DJing Township events and providing sound and audio services. He does not report to an office, has no set work hours, and has never received a performance evaluation in that role. Despite technically being a “full-time employee,” Richardson told OSC that he provides these services on an “as-needed” basis that does not amount to every workday —and there are occasions where he does not perform any work for the Township for periods of one to two weeks.

From 2021 through 2024, Richardson was paid over $180,000 in salary while receiving full benefits and pension-eligible service time. Meanwhile, since 2019, the Township has awarded at least $468,900 in small and large public contracts to businesses owned or controlled by Richardson, his wife, or his son for services that also included DJing and thus overlap with his assigned job duty. Those contracts included over $360,000 of opioid funds paid to the family’s businesses to DJ at concerts and to book additional performers. In other words, the Township paid a full-time employee again, as a vendor, through businesses he and his family controlled—a double payment for the same work. OSC found no evidence he ever worked close to the minimum hours he was already being paid for each week.

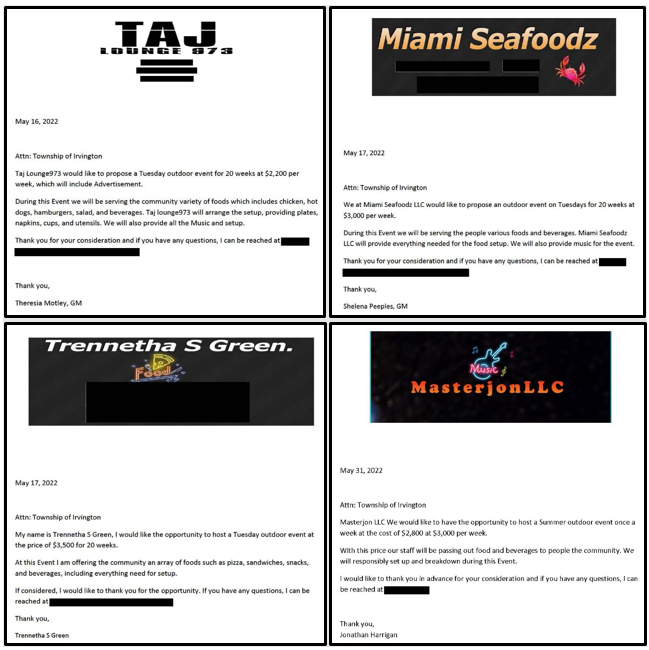

OSC also found that other funds intended for public health emergencies were funneled to Richardson. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the Township used grant funds to organize a series of “COVID Village” events and awarded a $38,000 DJ contract to Richardson through bid rigging. Two quotes came from businesses owned by Richardson or his wife; a third was submitted under his wife’s name, and the fourth—nearly identical in format and language—came from a DJ who is employed and managed by Richardson’s wife. The evidence suggests that Township officials solicited the quotes in full understanding that they all came from businesses owned by Richardson or his wife, in order to create the appearance of a competitive process without genuine competition.

In light of the findings in this report, OSC makes 31 recommendations to Irvington, other state agencies, the Legislature, and the public.

OSC is also making referrals to appropriate agencies for further investigation into its publicly reported findings and other concerning conduct identified during the investigation. These agencies include the Attorney General, the Treasury Department’s Division of Pensions and Benefits, Pension Fraud and Abuse Unit, Division of Purchase and Property, and Division of Taxation, as well as the Department of Community Affairs, Division of Local Government Services (DLGS). The misuse of these funds demands accountability and corrective action to ensure future spending serves the public interest—and the people harmed most by the opioid epidemic.

OSC’s oversight of opioid settlement spending is ongoing. Members of the public are encouraged to submit relevant information or tips—anonymously or with contact information—through the “Report Fraud, Waste, or Abuse” form available on OSC’s website.

Background

A. New Jersey and the Opioid Crisis

The U.S. opioid epidemic began in the 1980s with claims that opioids could safely treat non-cancer pain with low addiction risk, often based on weak evidence. In 1995, the FDA approved OxyContin, Purdue Pharma’s time-release oxycodone. Purdue’s aggressive marketing trained healthcare providers, funded educational programs, and backed groups promoting opioids for chronic pain, popularizing “pain as the fifth vital sign” and increasing prescriptions. By the early 2000s, OxyContin was the most prescribed and most used branded opioid. Even after abuse-deterrent versions launched in 2010, overdose deaths from natural (e.g., morphine) and semi-synthetic (e.g., OxyContin) opioids nearly quadrupled from 2000 to 2011, prompting the CDC to declare an epidemic. The crisis evolved through four waves: prescription opioids, heroin, illicit fentanyl, and, since 2020, polysubstance overdoses worsened by the COVID-19 pandemic. Since 1999, over a million Americans have died from overdoses, mostly involving opioids, costing over $1 trillion annually. Nearly a third of U.S. adults knows someone who died from overdose.

New Jersey has been severely impacted, ranking among the top U.S. jurisdictions for heroin overdose death rates from 2015 to 2020. In 2021, it recorded nearly 27 synthetic (e.g., fentanyl) opioid deaths per 100,000, ranking 19th nationally. Black/African-American residents, especially in Essex County, have been disproportionately affected. In 2020, Irvington alone accounted for nearly nine percent of the county’s reported uses of naloxone—a medication used to reverse opioid overdoses and commonly known by the brand name Narcan. By 2021, Essex County’s Black residents faced nearly 69 opioid overdose deaths per 100,000, with Irvington again accounting for over eight percent of Narcan administrations. In 2022, opioid deaths among Essex’s Black residents rose to nearly 81 per 100,000, and Narcan incidents in Irvington rose to 166, reflecting the ongoing “fourth wave” and the pandemic’s compounding impact.

There are some signs of progress. In 2023, New Jersey reported 2,816 drug overdose deaths—its first decline in a decade, mirroring national trends into 2024. More recently, data released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show that from December 2023 to December 2024, reported drug overdose deaths fell 26 percent nationally and 31 percent in New Jersey. Still, the crisis remains dire, with racial disparities persisting and over five residents dying daily in 2024. Amid uncertainties surrounding state and federal investment, resources like opioid settlement funds are crucial as the crisis persists.[1]

B. New Jersey’s Involvement in the National Opioid Settlements

The opioid epidemic has led to widespread litigation against pharmaceutical companies. New Jersey is set to receive over $1.1 billion over 18 years from settlements with manufacturers, distributors, and retailers, half managed by the State and the rest distributed to 262 eligible counties and municipalities. In 2021, New Jersey secured $641 million from major distributors and Johnson & Johnson, followed by $508.1 million from additional agreements in 2022, totaling over $1 billion. The state has also obtained smaller settlements, such as $16 million from McKinsey & Company, which faced criminal charges and penalties for advising opioid manufacturers. Additionally, New Jersey secured $5 million from Insys Therapeutics and participated in the Purdue bankruptcy settlement involving the Sackler family, which was struck down by the U.S. Supreme Court in 2024, with a revised plan now under review. As legal actions continue, New Jersey funds for prevention, treatment, and recovery initiatives may grow.

C. Legal Framework for Opioid Settlement Funds in New Jersey

The 2021 and 2022 national settlements require that funds be used for opioid remediation—programs addressing opioid addiction, treatment, and related harms—following a non-exhaustive list of “Approved Uses” included in each agreement. States and local governments must generally adhere to this framework, with limited exceptions.

On January 28, 2022, then-Acting Attorney General Andrew Bruck signed a Memorandum of Agreement (MOA) with New Jersey counties and municipalities to govern settlement fund use.[2] The MOA adopts the national settlements’ Approved Uses, requires funds to supplement—not replace--existing spending, and mandates five-year recordkeeping and annual reporting to the State.

To support oversight, Governor Murphy issued Executive Order 305 creating the Opioid Recovery and Remediation Fund Advisory Council (Advisory Council).[3] In 2023, this structure was formally established through Public Law 2023, chapter 25 (Senate Bill 783/Assembly Bill 1488 of the 2022-2023 Legislative Session) P.L. 2023, c.25, codified at N.J.S.A. 26:2G-39 to -43 (the 2023 Opioid Law).[4] The law designates DHS as the lead agency for distributing the State’s share; monitoring local spending to the extent required by the national settlements; and, in coordination with OSC and the Attorney General, ensuring compliance with the 2023 Opioid Law and the terms of the national settlements. DHS also handles reporting and allocates funds in consultation with the Advisory Council. Counties must establish their own advisory councils. Annual reports are required to the Governor and Legislature, and all spending of abatement funds must support approved, evidence-based or evidence-informed uses addressing “opioid use disorder and co-occurring conditions.”

D. Local Government Reporting to DHS on Opioid Settlement Fund Use

The Attorney General’s MOA requires participating counties and municipalities to report the amounts received, allocations of approved awards, and spending on both approved uses and administrative costs. All spending is subject to OSC oversight. For the 2023 and 2024 reporting cycles, OSC worked with DHS to monitor compliance. When reports were missing or incomplete, DHS notified OSC, which followed up with noncompliant governments. As of this report, three local governments remain delinquent for 2024; DHS will update its report once their data is received.

DHS has published county, municipal, and state-level reports for 2023 and 2024 on its “Opioid Settlements” website under “Reports (State & Subdivision Spending Reports).” Irvington submitted its 2023 and 2024 reports, located on pages 14 to 16 and 21 to 24, respectively, of the Essex County reports. In both years, Irvington reported spending opioid funds only on “Opioid Awareness Day” concerts. In 2023, it reported receiving $341,093 and spending $310,352. In 2024, it reported $1,093,018 received cumulatively since 2022, with $302,826 spent in that period. When asked if it engaged the public prior to spending opioid funds, Irvington answered, “No” in 2023 and “No, but [we] plan to in the future” in 2024.

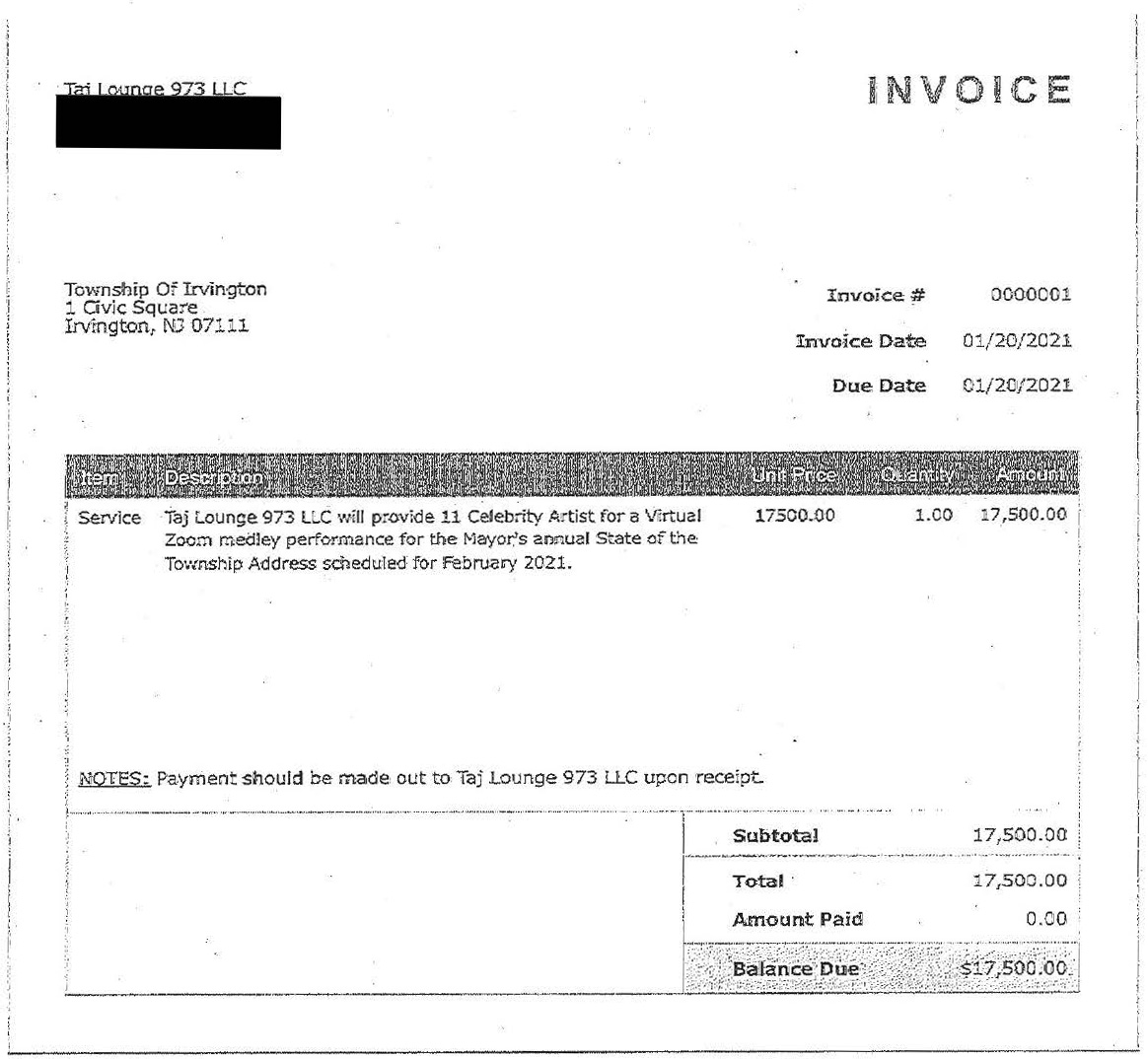

E. Advisory Letter from OSC to the Township Prior to the 2024 “Opioid Awareness Day” Concert

In 2023, the Township reported spending $310,352 in opioid funds on a one-day Opioid Awareness concert. Of that, $168,500 went to a business nominally owned by the immediate family of Richardson, a full-time Township employee, for music-related services. The contract was awarded without competitive bidding under the “Extraordinary Unspecifiable Services” (EUS) exception. OSC initiated a review in January 2024 by requesting documents from the Township. OSC interviewed the Qualified Purchasing Agent/Assistant Business Administrator (QPA) in May 2024.

The Township’s initial production raised concerns about: (1) likely misuse of the EUS exception; (2) potentially improper noncompetitive contracts involving a Township employee or their family, raising possible ethics or legal issues; and (3) use of opioid funds on programs potentially out of compliance with settlement terms or state law.

On May 21, 2024, OSC issued a confidential advisory letter outlining remedial steps related to a planned second event. The Township responded that: (1) EUS was appropriate for procuring artistic services; (2) no conflict existed because the vendors were owned by Richardson’s family, not Richardson himself; and (3) the concerts raised awareness and thus qualified as proper use of opioid funds.

The Township stated it believed it had a good-faith basis to proceed and committed to following OSC’s recommendations. OSC clarified that it does not cancel local events or typically direct local contracting decisions (with some exceptions not applicable here) and urged the Township to consider all remedial actions outlined in the advisory letter.

Methodology

OSC promotes financial oversight, accountability, and integrity across the Executive Branch, including state agencies and local governments. Its authority comes from two statutes: the law establishing the Office of the Inspector General (OIG), N.J.S.A. 52:15B-1 to 52:15B-16, and the law creating OSC as an independent office reporting directly to the Governor, N.J.S.A. 52:15C-1 to C-16.[5] OSC is empowered to conduct audits, investigations, inspections, and performance reviews; issue subpoenas; oversee taxpayer funds; and review public contracts. OSC reports its findings to the Governor, the Legislature, and the public.

OSC’s Audit Division has repeatedly reviewed Irvington Township since 2009, when it identified deficiencies in financial management, recordkeeping, internal controls, compliance, and personnel practices.[6] A 2011 follow-up found most deficiencies unaddressed.[7] In 2023, OSC again found little progress, including inadequate accounting, lack of employee evaluations, and contracts tainted by conflicts of interest.[8] Notably, the Township spent over $200,000 to lease space from a company partly owned by its Chief Financial Officer (CFO), who signed the sole bid for the lease, in violation of ethics laws. On March 6, 2024, OSC recommended that DLGS appoint a state fiscal monitor; no appointment has been made to date.

During a routine follow-up on implementation of its earlier recommendations, OSC’s Audit Division became aware of a $200,000 contract to spend national opioid funds on an “Opioids Awareness Event,” awarded through the rarely used EUS exception to public bidding under the New Jersey Local Public Contracts Law (LPCL), N.J.S.A. 40A:11-1 to -60. Noting the subject matter and the irregularity of the procurement, the Audit Division referred the matter to OSC’s Strategic Initiatives Unit (SIU) for further review. Among other things, SIU coordinates OSC’s oversight work relating to opioid funds under the 2023 Opioid Law.[9]

SIU reviewed Township procurement, personnel, and financial records; third-party documents; legal materials; and interviewed numerous Township officials and employees, including the Township’s QPA, a confidential aide to the Mayor, the Municipal Clerk, a former Director of Economic Development and Grants Oversight, a former Director of Health and Senior Services, the Director of Public Safety, the Director of Recreation, the Deputy Director of Health and Senior Services, the Business Administrator (BA), and the Mayor.

Although Irvington generally cooperated, it caused delays by slowly producing information, documents, and witnesses, and by taking over eight months to retain legal counsel for Richardson, eventually requiring OSC to seek court relief. By April 2025, the Township was noncompliant with two subpoenas, prompting a court to order Irvington to explain why it should not be compelled to produce the requested documents. The Township ultimately agreed to produce the outstanding documents, but did so months after the return date of the subpoenas and more than a week after the court-imposed deadline. Similarly, Richardson, along with his wife, Trennetha Green-Richardson, and their son, refused to cooperate for months, until a court compelled them to provide OSC with sworn statements. Richardson and Green-Richardson ultimately sat for interviews with OSC, but their son did not comply with the court’s order.

On April 15, per its standard procedures, OSC provided the Township with a nonpublic discussion draft of this report and invited the Township “to offer comments on any factual inaccuracies and present any other relevant information to OSC.” OSC explained that its investigation remained ongoing, but “given the Township’s delay in responding to OSC’s subpoenas and its recent solicitation of services for a potential third Opioid Awareness Day, OSC has determined that publishing a report is necessary to ensure transparency for the public.” Despite this, and before submitting any response to the discussion draft, the Township, several of its officials, and Antoine Richardson filed suit against OSC seeking to block publication of this report. Irvington accused OSC of denying it the chance to contest findings and omitting materials from the discussion draft that it considers favorable, such as a photograph of the Township Health Department’s table at the 2024 event—while ignoring that the Township had never provided OSC with the photograph in the first place.

After filing suit, the Township produced new records showing it had taken steps toward spending opioid funds on a 2025 Opioid Awareness Day, including a March 27, 2025 record showing over $38,000 was set aside for advertising—just one week after the Mayor and BA said no decision had been made to hold a 2025 concert. The Township also issued a Request for Proposals (RFP) for a 2025 concert. Given these developments, OSC determined that releasing its findings now serves the public interest, even as a limited portion of the investigation remains ongoing.

As with the Township, all individuals and businesses referenced in this report were given an opportunity to comment. OSC also provided DHS and the Attorney General with advance notice and an opportunity to comment on relevant findings. OSC considered all responses and addressed them where appropriate. Richardson, along with his wife, son, and their businesses, did not provide any comments in response to OSC’s discussion draft.

Findings

In 2023 and 2024, Irvington spent over $632,000 in opioid settlement funds on two single-day “Opioid Awareness Day” concerts. OSC found that this use of funds fell far short of the legal, ethical, and practical standards required for public money, especially funds meant to address a devastating public health crisis. Specifically, OSC found that:

- Irvington wasted and misspent $632,502.16 in opioid funds on two concerts with no evidence-based or evidence-informed justification, as required by state law. While entertainment-based events may, in some cases, support outreach goals, the limited health content at these events did not justify the scale of the spending, especially considering extravagant expenses such as over $350,000 on entertainment; more than $200,000 on billboards and other promotional materials; nearly $18,000 on food vending equipment and supplies like cotton candy and popcorn carts; $11,000 on generators; nearly $13,000 on “luxury VIP” trailer rentals, and more;

- Of the $632,502.16 in opioid funds that Irvington spent on the concerts, $368,500 was paid to businesses owned or controlled by Richardson, a full-time Township employee, or his immediate family, creating a clear conflict of interest;

- The Township improperly hired these businesses through a nonpublic, noncompetitive process using the EUS exception under the LPCL, even though the services did not meet the legal criteria and required procedures were not followed;

- Irvington does not track Richardson’s hours and performance, despite his dual role as salaried employee and paid vendor for similar services; and

- Richardson previously secured other Township contracts—including during the COVID-19 pandemic—through flawed procurement practices, including a sham solicitation that amounted to bid rigging, in which three of four quotes came from his wife or their jointly owned businesses, and the fourth came from a DJ who is employed and managed by Richardson’s wife. These other Township contracts, together with the Opioid Awareness Day contracts, amount to at least $468,900 in public funds awarded to businesses owned or controlled by Richardson and his immediate family members between 2021 and 2024.

Finally, although DHS is the “lead state agency” tasked with ensuring local governments properly spend opioid funds, it has provided limited oversight and insufficient guidance, increasing the risk of misuse statewide.

These findings reveal not only serious failures in Irvington’s management of opioid funds, but broader problems in its procurement and personnel practices—and missed opportunities at the state level to offer stronger support to local governments. The sections that follow detail each issue.

A. Irvington Misspent over $632,000 of Opioid Settlement Funds on Two Concerts that Lacked an Evidence-Based or Evidence-Informed Justification as Required by State Law

1. The Township’s Decision to Hold an Opioid Awareness Concert Was Not Evidence-Based or Evidence-Informed

In 2023, the Township decided to use its opioid funds on an awareness concert after a single directors’ meeting—without consulting its health and public safety departments, engaging stakeholders, or conducting research beyond a basic internet search to see if anyone else had held a similar event. While a concert with meaningful outreach might be a permissible use of opioid funds, the Township provided no evidence that its concert, held on June 10, 2023 in front of Irvington Town Hall, was designed or evaluated to serve that purpose. The expenditure—ultimately more than $632,000 across two events—was not grounded in evidence or public health standards and did not meet the legal requirements for spending opioid funds.

The settlement agreements contain a non-exhaustive list of approved uses for opioid funds, which the Attorney General’s MOA adopted. That list provides examples of appropriate expenditures which might align with an outreach concert such as media campaigns, stigma reduction initiatives, school-based prevention programs, or other evidence-based education programs. But the 2023 Opioid Law requires that all expenditures be either “evidence-based” or “evidence-informed,” setting an objective standard: the opioid funds must be used in a thoughtful, research-grounded manner.[10] These terms are not defined in statute but carry widely accepted meanings: “evidence-based” approaches have been rigorously evaluated and shown measurable results; “evidence-informed” strategies draw on the best available data and research, even if not formally tested.

Despite these standards, the Township did not apply any evidence-based or evidence-informed reasoning. Officials told OSC the decision was made after one directors’ meeting with the Mayor. With only a vague understanding that the funds were for “opioid-related events,” directors discussed “three or four” ideas—including a billboard campaign and Narcan distribution—before someone proposed a concert. The BA said directors agreed a concert would provide good outreach. According to the Mayor, Antoine Richardson—the DJ who was later awarded the contract—was discussed during the same meeting. Richardson himself remembered a phone call with multiple Township officials discussing which artists they wanted to perform at the concert. Officials recalled no follow-up discussions on how to spend the funds.

In its 2023 report to DHS, the Township claimed it “performed internal research on the benefits and effectiveness of Concerts and Festivals.” But the only “research” the BA could cite was a personal internet search. He told OSC:

I ran searches to see if other people had done concerts . . . I came across things . . . studies or articles . . . I thought there was enough information out there to say “yeah, having a concert wouldn’t be an issue.” I thought it was evidence-informed.

He also referred to childhood memories of drug awareness programs and recalled that a nonprofit, Partnership for a Drug-Free New Jersey (PDFNJ), held awareness concerts sometime between 2017 and 2019, though he could not recall specifics.

In court filings submitted months after OSC’s interview with the BA, he cited additional examples of outreach concerts and public health literature. He also argued public health practitioners often use platforms like Google Scholar. But none of this material informed the Township’s original decision. The documents the Township eventually provided to OSC—including articles, webpages, and press releases—were gathered well after the fact, many printed in 2025 in response to OSC’s inquiry. A program cannot be considered “evidence-based” or “evidence-informed” when the evidence is gathered only after the money is spent.

The only example the BA could confirm as influencing the 2023 decision was PDFNJ’s “Shout Down Drugs” concert series. But those events differ significantly: they involve a statewide contest in which students submit original music with prevention messages, culminating in a free showcase.[11] Winners receive up to $10,000 in music contracts. The events are clearly structured around education, engagement, and behavior change. Irvington’s concerts had no such framework.

Beyond the BA’s anecdotal input, the Township did not consult any professionals, public health experts, or community stakeholders. The CFO acknowledged that “a lot of organizations” reached out with proposals—such as police-assisted referrals or treatment partnerships—but the Township declined to follow up. Asked whether those groups recommended how to spend the funds, the CFO responded, “I mean, they were pitching their program. So I assume that’s their opinion.” When asked if the Township engaged with survivors or residents affected by the opioid crisis, the Mayor said such outreach would be “very difficult” and the goal was to “make it comfortable” for people to share their stories.

No one ensured the decision met evidence-informed standards. The CFO said he believed the funds were used “in the areas that were appropriate based upon the limited . . . information we had,” and that he had read the Attorney General’s MOA “at one point.” The BA said the CFO was “ultimately responsible,” but conceded the CFO would not necessarily know whether the decision was evidence-informed. The BA assumed the health department had been consulted.

In reality, the health department played no role. The Health Director at the time said she and her staff were not involved in the event’s planning, had not attended any directors’ meetings on the subject, and only learned about the concert from a flyer. No one asked her to participate, but she attended on her own and brought informational handouts she had printed from an internet search. The Director of Public Safety also told OSC that no one from the Township consulted his department on using the opioid settlement funds on the concerts other than providing security for the events.

The Township’s decision was not evidence-informed. While the statute does not define that term precisely, under any reasonable reading it requires far more than anecdotes and a cursory online search. The Township’s rejection of stakeholder input, failure to engage public health staff, and reliance on after-the-fact justifications all reflect a troubling disregard for the intent of opioid funds—and help explain why the resulting expenditure failed to serve the community in a meaningful way.

2. Irvington Misused the EUS Exception to Public Bidding for the 2023 Event in Violation of the LPCL

Not only did the Township fail to implement a thoughtful, evidence-based approach to spending opioid funds on a concert—it also awarded $168,500 to a single vendor through a non-public, non-competitive process that did not comply with state law. Specifically, the Township violated the LPCL by improperly relying on the EUS exception. On April 10, 2023, the Township passed a resolution awarding a contract for $168,500 to Taj Lounge 973, LLC for the 2023 Opioid Awareness Event, characterizing the services as “Extraordinary Unspecified[sic] Services, as defined by NJSA 40A:11-2 (7) [that] are not required to be publicly bid as provided for in [N.J.S.A.] 40A:11-5(1)(a)(ii).”

The LPCL defines an EUS as “specialized and qualitative in nature requiring expertise, extensive training and proven reputation in the field of endeavor.” A contract over the bid threshold may proceed without public bidding only after documenting efforts to secure competitive quotations and a written determination that soliciting quotations is impracticable. The exception must be construed narrowly in favor of competitive bidding “whenever possible.”

DLGS regulations further limit the EUS exception, requiring (1) the qualitative nature cannot reasonably be described by written specifications, (2) if specifications can be prepared, they must be, (3) prior bids or ongoing services are presumed not to qualify unless justified in writing, and (4) a designated official must certify in detail why the contract meets legal criteria—mere recitation of statutory language is insufficient. A general “desire to have a reliable job performed” is also insufficient.

DLGS explains that before awarding such a contract, the official must certify why specifications cannot reasonably be drafted, outline solicitation efforts, and describe how the work meets legal requirements. DLGS provides a standard format, requiring the contracting official to provide “a clear description of the nature of the work,” a detailed explanation beyond rephrasing the statute, and a list of vendors contacted and their prices and terms.[12] DLGS also recommends competitive contracting under N.J.S.A. 40A:11-4.1 (k) instead of the EUS exception.

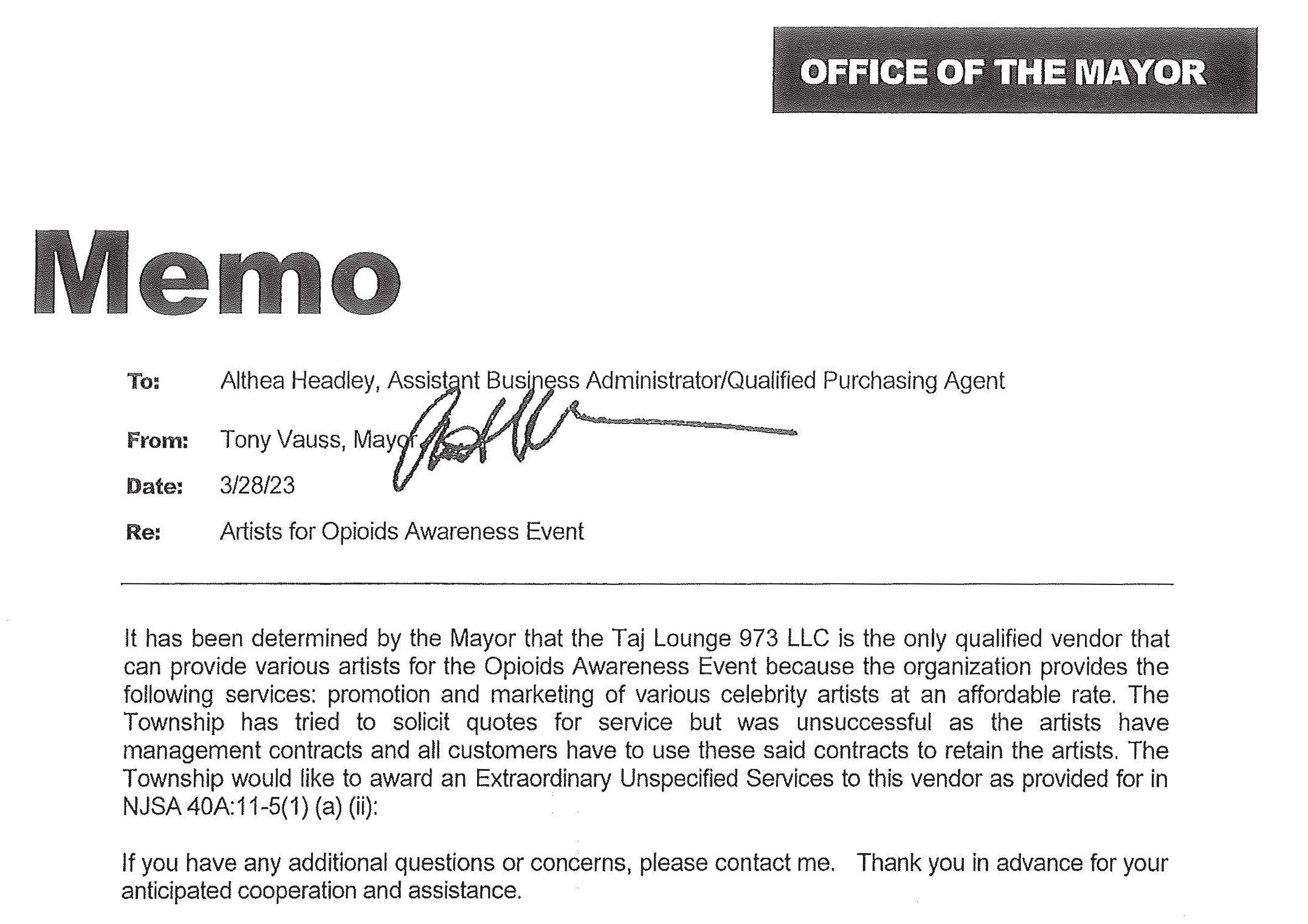

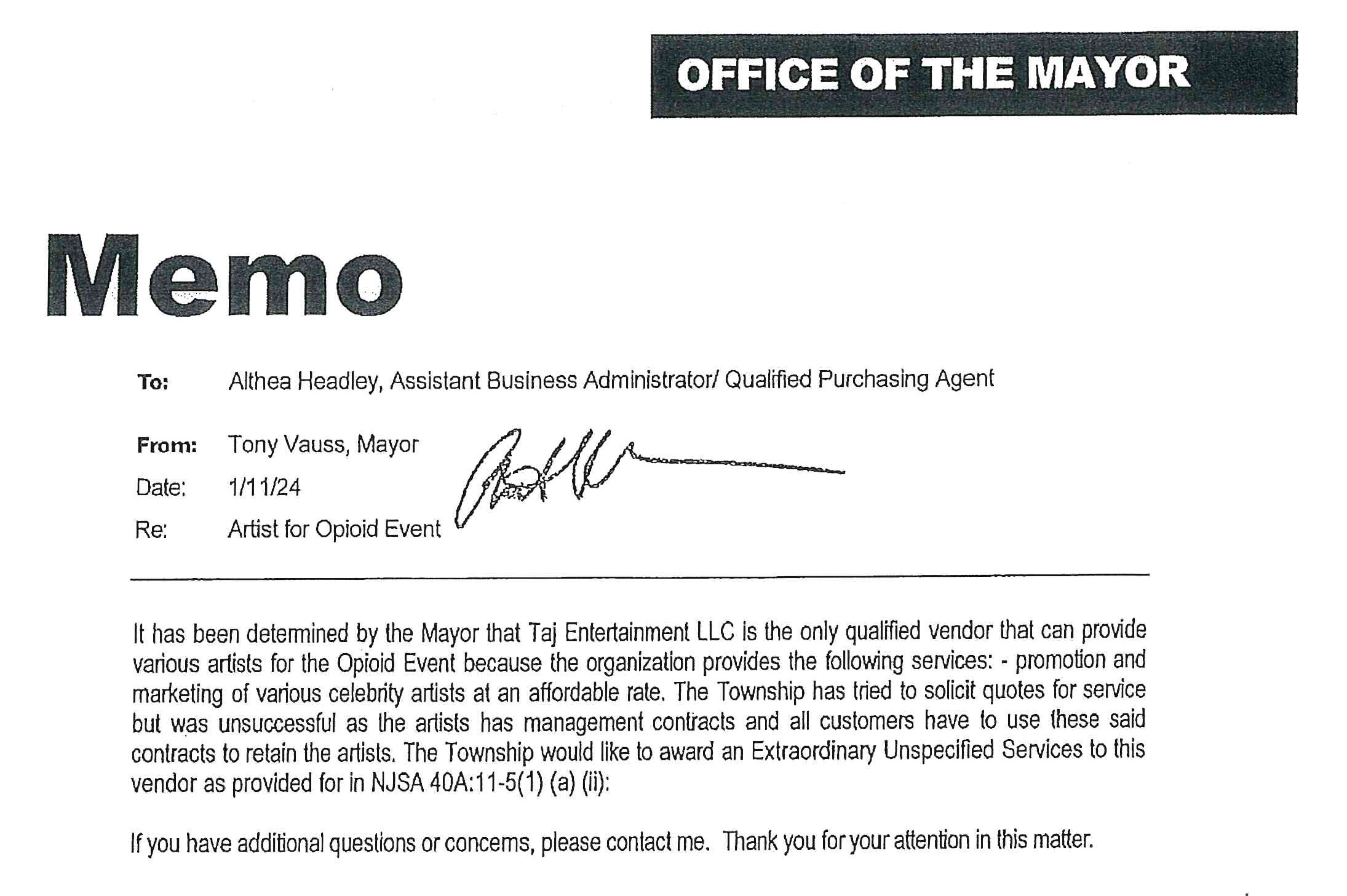

Here, the Township failed to meet these requirements. It did not adequately document efforts to solicit quotations or explain why doing so was impracticable. The Township provided a March 28, 2023 memorandum the QPA told OSC was intended as the certification.

Figure 1: Memorandum to QPA about 2023 Opioids Awareness Event

However, the memorandum did not include necessary details such as a description of the work, reasons why specifications could not be drafted, or a summary of informal solicitation efforts. Instead, it mirrored statutory language without providing the required specifics. A March 28, 2023 email from the QPA to the Mayor’s assistant requested that the assistant take the attached document containing the EUS determination, put it on the Mayor’s letterhead, stamp it, and return it to the QPA. When questioned by OSC, the QPA mentioned that the mayor had prepared the memo, not her. She expressed that, in her professional opinion, many items could be bid, although she was sometimes informed otherwise. She agreed with the decision to use the EUS exception after understanding more about contracting with musical artists, despite initially questioning the sole vendor choice. When OSC spoke with the Mayor, he claimed the QPA prepared the memorandum, but he had his assistant stamp-sign it because he was told, “if you want to have the concert, this is what you have to do.” Upon follow-up, the QPA stated she prepared the language and did not remember attributing it to the Mayor.

Neither the QPA nor the Mayor could identify any efforts to seek quotations from other vendors. The assertion that Taj Lounge 973 was “the only qualified vendor” is inconsistent with DLGS rules, which state that a “sole source” claim alone does not justify bypassing bidding requirements. The memorandum lacked the thoroughness needed to meet LPCL standards.

The QPA told OSC the EUS exception was appropriate due to the vendor’s unique access to artists. She explained bookings are handled through intermediaries, making direct solicitation difficult. Even if true, the memorandum still failed to explain in writing why solicitation was impracticable.

More recently, the Township has tried to retroactively justify its prior use of the EUS exception by pointing to steps taken in 2025. Specifically, the QPA cited the Township’s issuance of a RFP on March 11 and April 2, 2025, seeking a “Promotor and musical management consultant for opioid concert” for a potential 2025 Opioid Awareness Day. As of her April 29, 2025 certification in support of litigation against OSC, no proposals had been received. In an April 3, 2025 interview, the QPA told OSC the RFP went “above and beyond” LPCL requirements and that the lack of vendor interest validated the earlier use of the EUS exception in 2023 and 2024. OSC disagrees. The RFP represents the minimum effort required under the LPCL—a good-faith attempt to secure competition—and its existence underscores that the Township was always capable of preparing specifications for these services. Efforts made in 2025 do not cure earlier procurement failures.

More concerning, the Township’s response to OSC’s findings evinces a fundamental misunderstanding of which LPCL provisions apply, or an after-the-fact attempt to justify its expenditure. In its May 29, 2024 letter to OSC, the Township claimed for the first time that its expenditure was appropriate under N.J.S.A. 40A:11-5(1)(k) (“subsection (k)”), arguing that “EUS may be used for the acquisition of artistic services.”

But subsection (k) is a separate exception entirely. It allows contracts for “artifacts or other items of unique intrinsic, artistic, or historical character” without public bidding. Even if applicable, the Township did not award these contracts under subsection (k). Its resolutions cite only N.J.S.A. 40A:11-5(1)(a)(ii), the EUS exception.

Yet in its response to OSC’s draft report and its lawsuit, the Township repeatedly conflates subsection (k) with the EUS exception, arguing “the Extraordinary Unspecifiable Services exception set forth in N.J.S.A. 40A:11-5(1)(k) (‘EUS exception’) is a highly technical process that is to be carried out by licensed and trained QPA’s,” and “The Township did not . . . misuse the [EUS] statute, N.J.S.A. 40A:11-5(1)(k), in its procurement process.” This argument shows either a fundamental misunderstanding or a misleading attempt to justify the nonpublic procurements under a statute the Township did not rely on when awarding the contracts.

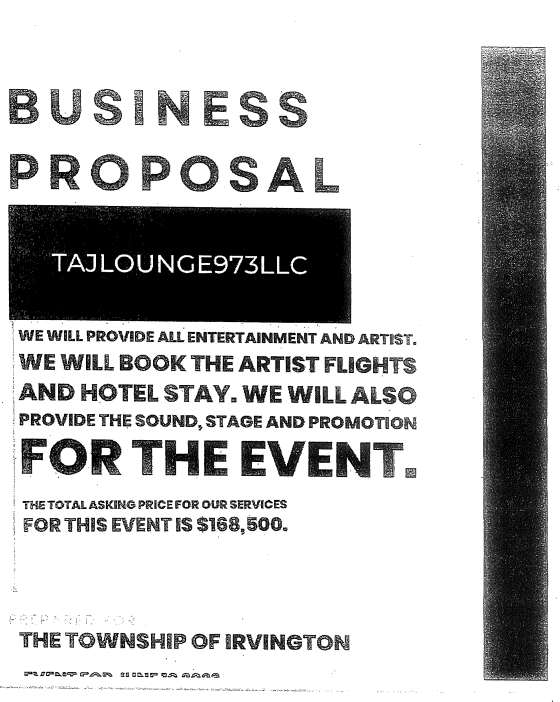

Other procurement records for the 2023 concert further reflect the Township’s lax approach. On March 20, 2023, Antoine Richardson sent an email to the QPA titled, “This is the budget for the opium 2023 concert in irvington nj,” and stating only: “For all entertainment and sound and stage $169,500.” The QPA advised Richardson to submit a proposal, and the written proposal attached to the resolution consisted of four vague sentences. See Figure 2 below.

Figure 2: Business Proposal from Taj Lounge 973, LLC

In its May 29, 2024 letter to OSC, the Township claimed that “standard goods and services” provided by Taj Lounge, “such as sound, stage, event planning, and promotional services . . . are under the Township’s bid threshold of $44,000.” The Township repeated this claim in its more recent lawsuit against OSC, stating that the Township confirmed each component was below the $44,000 bid threshold, obtained quotes from multiple vendors, and did not procure these services under the EUS exception. But Green-Richardson told OSC that she never gave the Township an itemized invoice showing what the non-artistic services cost, and only ever provided the “general number” quoted in the proposal in Figure 2 above. The Township’s claim is also inconsistent with all of the records and statements the Township has produced to OSC since its inquiry began in January 2024. The Township has not provided OSC with other quotes for “support services,” invoices, or documents showing costs. Nor has it explained how it “confirmed” these costs when the proposal quoted $168,500.00 for artists, travel, “sound, stage and promotion” without a breakdown. On the contrary, numerous officials, including the Mayor, stated clearly that they did not know how the funds were spent by the vendor.

At best, the Township’s reliance on a non-competitive process to award a contract to a business owned or controlled by Richardson—a full-time Township employee—or his immediate family creates an appearance of favoritism and carelessness. At worst it reflects a disregard for public procurement law, the purpose of the opioid settlements, and—more troublingly—the vulnerable residents who depend on these funds to recover from opioid addiction.[13]

3. The 2023 Event Demonstrated Minimal Connections to Opioid Awareness and Education

The Township spent over $350,000 on its 2023 Opioid Awareness Day concert. However, the Township has not provided evidence to OSC that the event effectively conveyed meaningful awareness or education about opioid addiction. On the contrary, the evidence shows that the event did not meaningfully promote awareness about opioid addiction or available resources. There were no tracked metrics, attendance estimates, or lists of health- or opioid-related vendors. The only verified attendee relating to addiction was the Rutgers Medications for Addiction Treatment Center of Excellence.

Although the Township claims the event incorporated other permissible uses, such as Narcan distribution, it was unable to confirm whether Narcan was actually distributed in 2023. The Attorney General’s MOA lists free Narcan distribution as an approved use, but the Public Safety Director did not recall the Police Department distributing Narcan and noted that liability concerns likely prevented it. He suggested the Health Department might have distributed it but was unsure. The former Health Director said the Department had no access to Narcan at that time. Even if Narcan had been distributed, it would not justify spending over $350,000 on a single-day concert, which included $168,500 on entertainment, nearly $100,000 on mobile and stationary billboards, $1,600 on a shaved ice machine, almost $4,000 on a popcorn machine, more than $1,500 on a cotton candy machine, about $5,500 on an ice maker, $11,000 on generators, $6,600 on luxury rental trailers, and more. Additional resources related to opioid addiction could have simply been incorporated into other established events like Unity Day—a well-attended annual festival featuring food, music, and public health outreach—which officials told OSC typically draws more residents than the opioid events.

Additionally, the Township claims it included a media campaign as part of the concert, spending $82,248 on “Opioid Awareness Billboards.” But the CFO told OSC that these were primarily to promote the concert, and no 2023 ads were provided to verify their content. Flyers produced by the Township only advertised the event and contained no educational or resource-focused content. The flyers did, however, prominently feature images of the Mayor and musical performers, including Richardson, who appears in the flyer as “DJ Qua.”

Figure 3: Flyer of 2023 Opioid Awareness Day Concert

There is little evidence that the event’s messaging was more substantive than its marketing. The Township claimed that the Mayor, councilmembers, and artists spoke about the opioid crisis. The Mayor told OSC they “had a script to talk about the dangers of opioids . . . and we got up on the microphone and read the script.” The Mayor could not remember who prepared it but said it included information from “the internet,” “talking points,” and “facts about opioids.” In response to this report, the Mayor claims he “educated residents . . . on the risk of prescriptions, drug addiction, and overdose,” urged consulting doctors about non-opioid options, careful dosing, reporting side effects, and avoiding mixing substances. He also claims that officials discussed safe storage, disposal, needle exchanges, and prescription drop-off locations. Despite multiple opportunities, the Township has not produced the script or any health materials it claims were distributed.

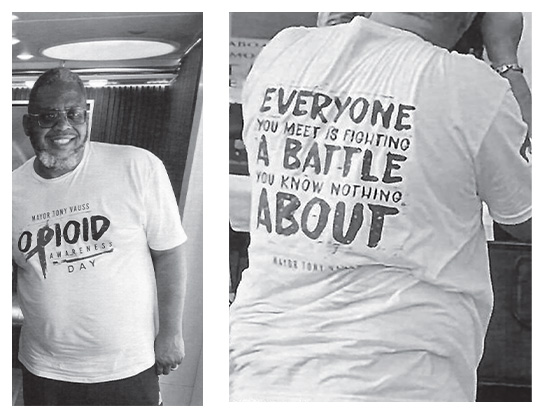

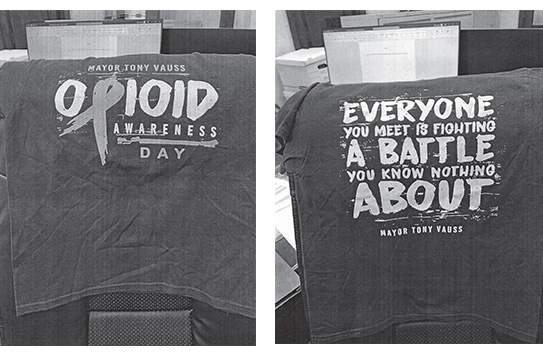

The Township did provide OSC with an image of t-shirts handed out at the event, which read “Opioid Awareness Day” on the front, “Everyone you meet is fighting a battle you know nothing about” on the back, and “Mayor Tony Vauss” on both sides.

Figure 4: Photograph of 2023 T-Shirt

For his part, Antoine Richardson told OSC that he performed a DJ set, during which he told the crowd to “stay clean,” “say no to drugs,” and “do not use.” Richardson also said that each artist that took the stage and said something to the effect of, “Kids, stay in school, stay away from drugs.”

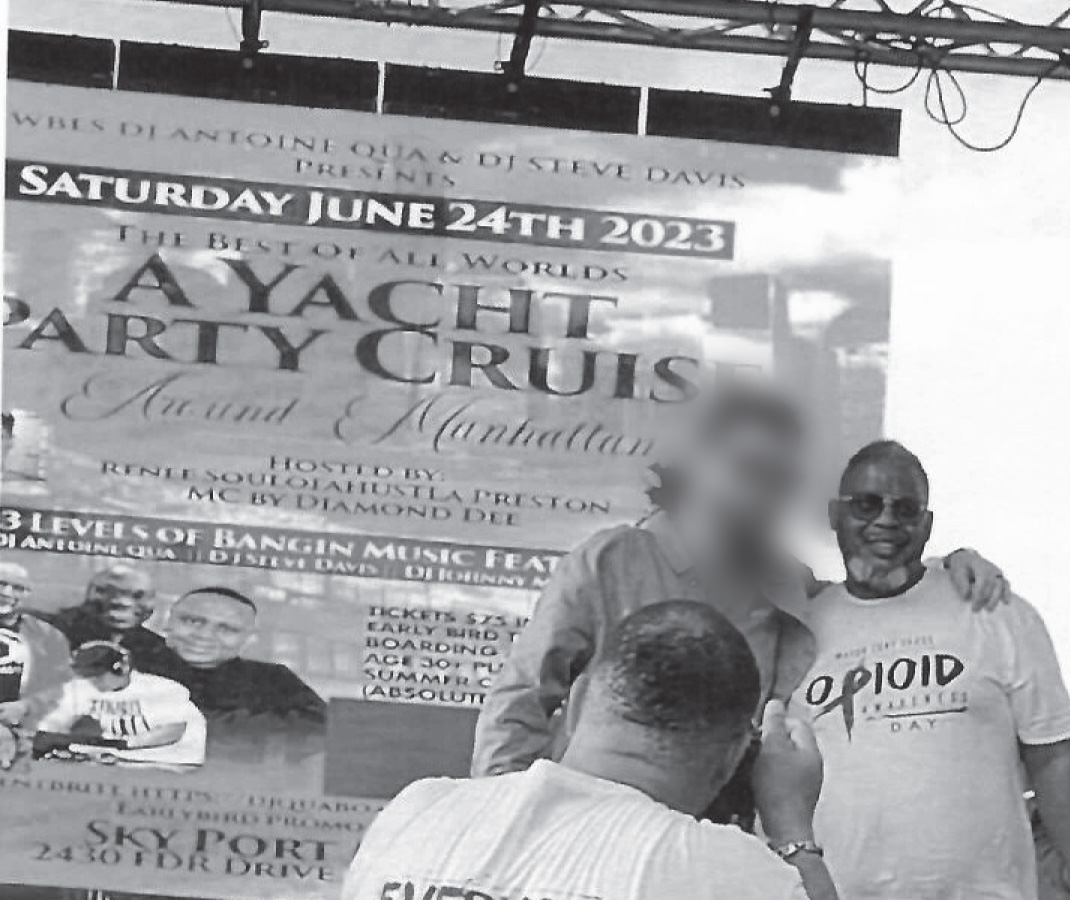

The only verified message displayed on stage was an ad for a “Yacht Party Cruise Around Manhattan” presented by Richardson (using his stage name). The stage display made no mention of opioids.

Figure 5: Photograph of 2023 Stage Display

The Township has not produced any other messaging or resources from the event. The former Health Director, who attended on her own, recalled the Health Department had a table with general health literature, including some opioid-related materials printed from the internet for the event. She could not recall the substance or source of the materials, and no copies were kept. Some attendees reportedly asked about general health and addiction. The former Health Director said she played no role in selecting vendors, had no interaction with other tables, and did not recall seeing any other vendors or opioid resources beyond her Department’s printouts.

While community events with entertainment can support outreach efforts and may be permissible under settlement agreements and state law under certain circumstances, the health messaging at the 2023 concert was minimal and did not justify spending $168,500 of opioid funds on musical performances, along with an additional $185,000 on expenses ranging from advertising to popcorn, shaved ice, cotton candy, and ice machines, as well as generators and luxury trailer rentals.

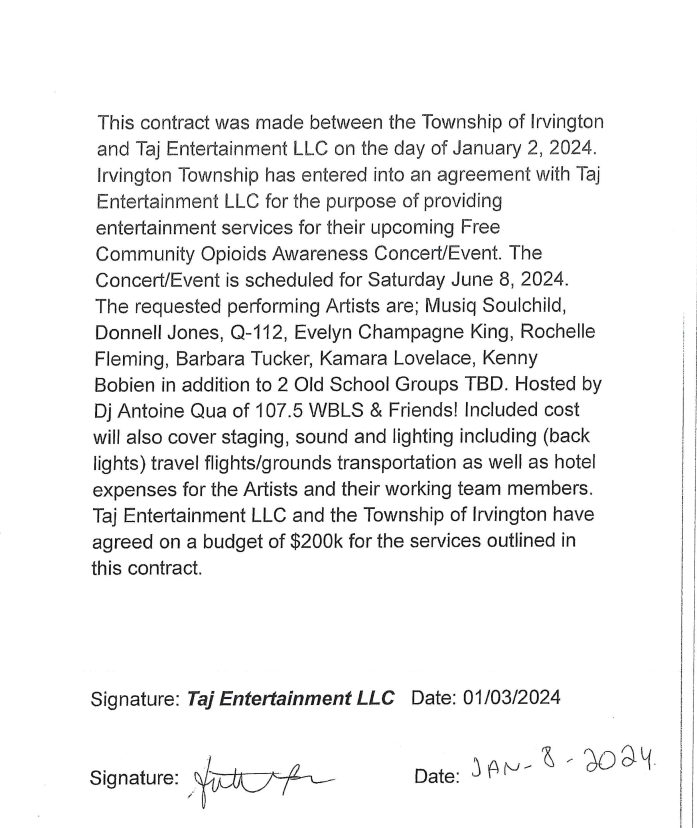

4. The Township’s Planning and Procurement Processes for the 2024 Event Were Similarly Flawed

The Township again failed to demonstrate that its spending met the required evidence-informed standard for its second event, held on June 8, 2024, in front of Town Hall. Officials did not evaluate whether the first event achieved any measurable public health benefit, nor did they consider whether a second concert was the best use of limited opioid funds. The BA told OSC he believed the first event was successful due to its “very large turnout,” and that “everyone was on board with repeating the process,” aiming for “an even bigger turnout” and “even more services” in 2024. In response to this Report, the BA stated “[p]reliminary crowd estimates, based on photo analysis and on-site assessments, suggest attendance exceeding 3,000.” However, the Township has not provided OSC with any documentation of these assessments–who conducted them, how estimates were calculated, when they were done, or whether they played any role in justifying the continued expenditure of opioid funds.

After receiving additional funds in FY 2024, the Mayor recalled an informal discussion with his team:

This is how much money we have . . . what do we want to do? Do we want to have another concert? Can we make it bigger, better, bigger artists, bigger stars, more people come out? . . . Build upon it every year.”

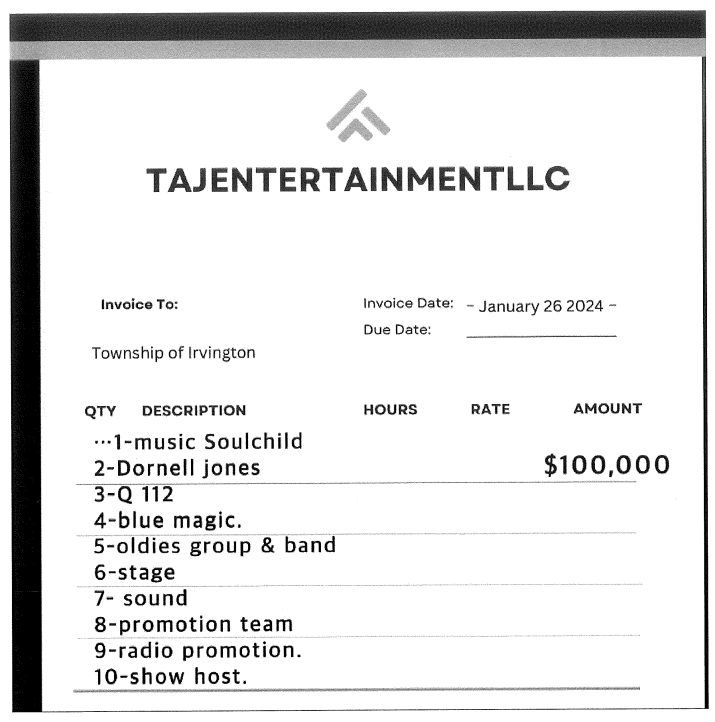

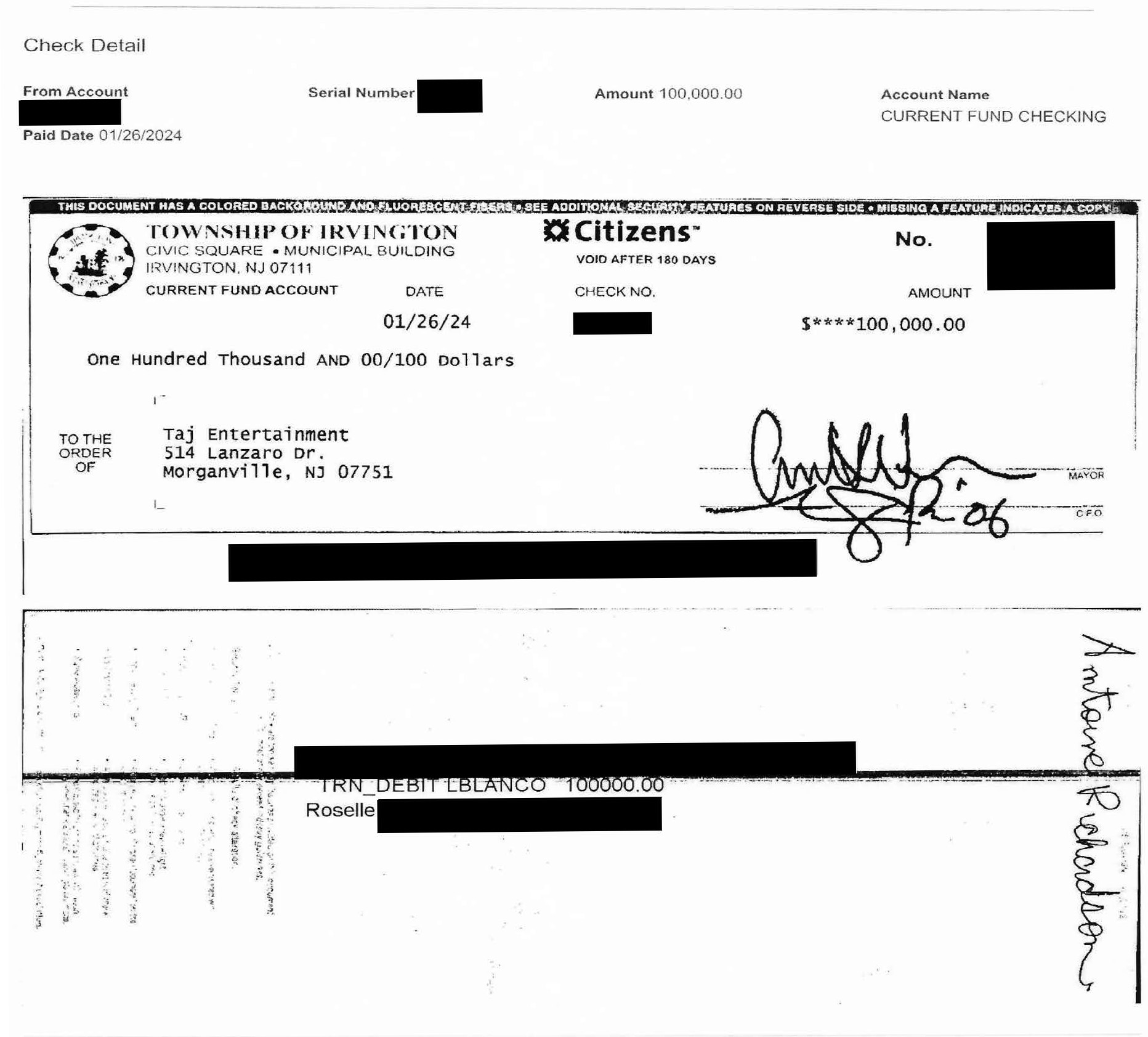

The Mayor described proposing musical acts he thought would be “big draws” and checking with Richardson “whether we have a shot at getting them.” Richardson, too recalled that the process for the 2024 concert was the same as 2023—at some point, he spoke with a group of Township officials over the phone about which artists they wanted to hire. On January 25, 2024, the Township passed a resolution awarding $200,000 to Taj Entertainment LLC—over $30,000 more than the previous year. Like 2023, the Township again used the EUS exception and nearly identical resolution language. The 2024 resolution stipulated paying the vendor $100,000 upfront, with the balance due after the event.

Despite the increased cost, the Township has not explained how the 2024 concert differed in scope or services. The resolution referenced an “attached proposal,” but the document—labeled a “contract” and dated January 2, 2024—simply listed eight musical artists and basic references to staging, sound, lighting, and travel expenses. It stated the Township and vendor “agreed on a budget of $200k.” According to the QPA, this was the vendor’s proposal.

Figure 6: 2024 Event Contract

Like the prior year, the 2024 proposal did not include a breakdown of individual service costs, even though the Township claimed it “confirmed” that staging, sound, event coordination, and promotion were each under the $44,000 bid threshold. The Township also failed to provide OSC with the required vendor quotes that purportedly supported these figures. Green-Richardson—who said she runs Taj Entertainment even though the business is nominally owned by her son—told OSC that she prepared the proposal in Figure 6 and did not provide the Township with a more itemized breakdown of the $200,000 price. She also identified Antoine Richardson’s signature at the bottom left of the proposal and said he often signs forms on behalf of the businesses. Again, the Township’s claim that it “confirmed” the costs of staging and sound is not supported by any records the Township has produced since 2024 and contradicts statements from multiple officials, including the Mayor, who told OSC they did not know how the vendor spent the funds. Richardson claimed some artists charged less than their normal fees because of his relationship with them, but none worked for free. Green-Richardson refused to tell OSC how much they paid each musical performer and how much the businesses profited from the contracts, while Richardson claimed not to recall.

The documents the Township did provide included a January 11, 2024 memorandum from the Mayor to the QPA–nearly identical to the one submitted in March 2023. Once again, it failed to meet EUS requirements and merely echoed statutory language:

Figure 7: Memorandum to QPA about 2024 Opioid Event

The 2024 agreement also lacked a clear scope of services—an issue OSC identified as being a problem in Irvington in 2009 and 2011 reports. Although it referenced a “scope of services” to be provided by the Township Attorney, no such document has been produced. Instead, the Township submitted a document labeled as an invoice from Taj Entertainment, dated January 26, 2024—the same day the Township created a purchase order for the initial $100,000 payment. The “invoice” mirrored the vague language of the proposal, listing artists and general categories such as “stage,” “sound,” and “promotion.” Whether this or the earlier proposal was intended as the final scope of work is unknown. Either way, the documentation again failed to provide the level of specificity and accountability OSC has repeatedly recommended.

Figure 8: Taj Entertainment LLC Invoice to Irvington for 2024 Event

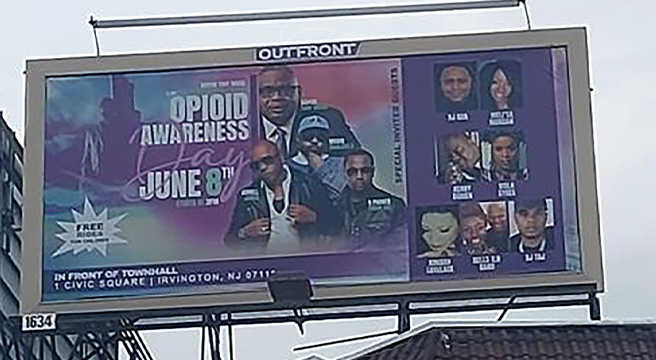

In addition to hiring Taj Entertainment LLC, the Township paid $33,150 to Out Front Media on March 25, 2024, for billboard ads. Invoices show at least five billboards displayed April 15 to June 9, 2024. The resolution stated the contract aimed to promote “Opioid Awareness information” to residents, but images of the billboards show that they primarily advertised the concert (and Mayor Vauss) with no clear public health messaging.[14]

Figure 9: Billboard Advertisement of the 2024 Event

Although the Township contracted with entertainment and media vendors by January and March, its earliest record of any health-related outreach came months later. On May 2, 2024, a Rutgers-affiliated outreach coordinator emailed the Township about a meeting to discuss potential collaboration opportunities on multiple health-related issues. The Township’s own Health and Wellness Outreach Coordinator responded five days later, referencing the “Opioid Concert on June 15” as one example. There is no evidence that the Township consulted Rutgers or any other public health experts about the planning of the event. And this late-stage contact, more than three months after the artist contracts, suggests that health service providers were an afterthought, not an integral part of the original planning.

5. While the Township Contacted Relevant Vendors to Attend the 2024 Event, the Concert Still Likely had Minimal Efficacy as an Awareness Event

OSC verified that public and private health-related vendors attended the 2024 Event, including counseling, addiction treatment, and behavioral health centers.[15] According to the Township, the Rutgers Medications for Addiction Treatment Center of Excellence provided onsite consultations with a clinician. The Township also produced a letter from the Center dated April 30, 2025, expressing its support for the concerts. In response to OSC‘s inquiry, Rutgers confirmed that Center staff attended both the 2023 and 2024 events and drafted the April 30 letter upon request from the Township‘s legal counsel. Rutgers advised that while it supports “the opportunity for public outreach at community events,“ its letter “was not an endorsement of the Event or the manner in which the Township administered or funded the Event.“

In addition to Rutgers, the Irvington Health Department also had a table with handouts and pamphlets. According to the Deputy Health Director, some vendors unable to attend provided materials for distribution. However, the Township has not provided OSC with copies of any health-related materials distributed. At least one vendor had already packed up and left shortly after 4:00 p.m., though the Event began at 3:00 p.m.

Despite spending nearly $280,000 on the 2024 concert, the Township did not purchase any Narcan for the event. Instead, on June 3, 2024—five days before the concert, and roughly two weeks after OSC expressed its concerns in a confidential advisory letter—the Township asked Family Connections, Inc.’s Alcohol and Drug Abuse Prevention Team (ADAPT) Coalition if it could “provide Narcan kits for us to place on the [Health Department] table with some of your literature?” The Township asked for a total of 50 kits, which ADAPT indicated it would ask Essex County to provide. It is unclear how many kits were ultimately donated. But in response to this Report, the Township provided OSC with a photo showing several Narcan kits on the Health Department’s table.

Figure 10: Irvington’s Health Department Table with Narcan at the 2024 Event

The Township also provided a document titled “Township of Irvington Health Department Sign-in Sheet – Opioid" dated June 8, 2024, which lists the names of 57 attendees. In a May 5, 2025 email, the current Health Director told the BA that the sign-in sheet reflected attendees who were given Narcan and any other products that were on display at the Health Department table. The sheet does not record what each person took. In his May 2025 email, the current Health Director said the Township still possessed “twelve remaining Narcan” kits that it will give to its “public health nurses.” In its response to this Report, the Township also asserted for the first time that four individuals “sought treatment on-site,” but it has not produced any additional details or documentation.

In addition, four or five tents or tables sold consumer goods such as cigars, purses, dresses, shirts, and hats, alongside at least six food vendors. Officials stated all vendors were approved by the Recreation Department and paid a fee. Meanwhile, the Township failed to demonstrate any substantial opioid-related messaging or resources. Like the 2023 concert, the 2024 concert featured brief remarks from the Mayor, councilmembers, and according to Richardson, from musical artists during their performances. An OSC investigator witnessed Councilmember At-Large Darlene Brown speak after a short introduction by the Mayor:

So this is the second year that we’re having this concert. Every year we want to have this to bring awareness to the opioid epidemic. And I’m going to introduce one of our councilpeople, who’s going to talk a little bit about that.

Councilmember Brown then delivered a one-minute speech:

Good afternoon Irvington; good afternoon. Today we bring awareness to opioid misuse, abuse. We bring awareness. The opioid crisis does not only impact the community and families but also places a tremendous strain on healthcare systems and resources. The economic burden of opioid misuse and addiction is staggering, with estimates indicating that the United States spends millions of dollars each year on healthcare costs, criminal justice expenses, and lost productivity associated with the opioid epidemic. Again, I am your councilwoman-at-large. I want you guys to enjoy the day here in Irvington.

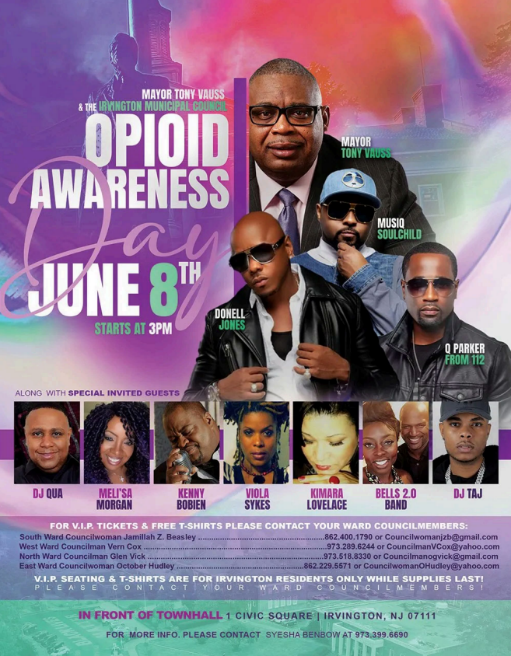

The investigator also observed an individual take the stage to “warm up” the crowd with the exclamation, “Irvington, New Jersey—We love our Mayor!” Notably, none of the health vendors was invited to speak, and promotional materials prominently featured Mayor Vauss while omitting any information about opioid addiction or treatment resources. The event flyer, like the prior year’s, emphasized musical acts and the Mayor’s image over public health messaging and included no substantive guidance on where or how to get help. See Figure 11 below.

Figure 11: Flyer of 2024 Opioid Awareness Day Concert

T-shirts distributed at the event read “Opioid Awareness Day” on the front, “Everyone you meet is fighting a battle you know nothing about” on the back—alongside “Mayor Tony Vauss” printed on both sides.

Figure 12: Photograph of 2024 T-Shirt

No opioid-related information appeared on stage, though two large posters of Mayor Vauss flanked it.

Figure 13: Photograph of 2024 Stage Display

Taken together, the evidence suggests the event’s primary purpose was not to educate or assist the public but to host a party, leaving a few brief opioid mentions as a gesture rather than a substantive focus.

6. The Township Wasted $632,502.16 on Both Events Without Evaluating the Reasonableness of the Expenses

As of June 30, 2024, the Township reported receiving $1,093,018 in opioid funds. It reported spending $310,352 in 2023 and $302,826 in 2024, for a total of $613,178. According to the CFO, this entire amount related to the 2023 and 2024 Opioid Awareness Day events, including vendor payments, t-shirts, flyers, and billboards.

However, the Township’s own accounting of its expenses shows that it spent $632,502.16 on both concerts. A significant portion of the funds—$368,500—was awarded to businesses owned or controlled by Richardson and his immediate family (the “Taj vendors”) to provide musical artists and unspecified “sound, stage, event planning, and promotional services.”

Other significant expenditures of opioid settlement funds for the 2023 and 2024 concerts include:

- $115,398 on stationary billboards that promoted the concert without conveying any meaningful awareness message;

- At least $53,525 on other promotional materials, copies of which have not been provided to OSC, including $16,000 to “Stratgic [sic] Marketing Group LLC” for mobile billboards that the owner described as featuring an image of Mayor Vauss in a suit with his arms folded;[16]

- $34,445 on the t-shirts pictured above;

- $29,161 to purchase eight generators and food vending equipment, including an ice maker; popcorn, cotton candy, and flavor ice machines and serving carts; a hot food display stand; and a coffee urn;

- $2,373 spent on “catering” provided at an unspecified time and location by 72 Lyons Ave. Corp., operating as “Marlo’s Lounge”; and

- $12,648 on “38’ Luxury VIP Talent Rental” trailers.[17]

The Township also reported police overtime for the concerts:

- 2023: 206.75 hours; $11,416.21 officers

- 2024: 133 hours; $5,810.18 officers

The Public Safety Director was unsure whether this overtime was paid with opioid funds. According to the CFO, vendor licensing fees collected during the events were deposited into the general fund and did not offset event costs.

Despite spending hundreds of thousands of dollars, the Township had no way to determine if its payments to the Taj vendors were reasonable. The agreements with the Taj vendors described vague services like “entertainment, sound, stage, promotion and artists,” with no itemized breakdowns or deliverables. Vendors were to perform “under the supervision and discretion and at the pleasure of the Mayor.” The Township received no invoices detailing how vendors or performers were paid.

Although he was responsible for ensuring the funds were used for their intended purpose of addressing the opioid crisis, Mayor Vauss was unconcerned about who actually received the funding. When asked if he knew how the Taj vendors spent the funds, the Mayor replied, “No. I don’t know why I would.”

OSC: Do you have any understanding of how the funds that were paid to Taj Lounge 973 were used?

Mayor Vauss: What do you mean?

OSC: So, they were paid 165 some-odd [thousand] dollars—do you have any understanding of how they took that money and what they used it—and how they spent it?

Mayor Vauss: No.

OSC: Okay.

Mayor Vauss: I don’t know why I would.

OSC: No, I’m just asking if you had any understanding—well, he’s being paid 160,000 plus [thousand] dollars—

Mayor Vauss: Mm-hmm.

OSC: Using opioid funds—

Mayor Vauss: Mm-hmm.

OSC: And I was just curious if you had any knowledge about how much he paid the artist that he procured, how much he paid himself, how much he paid immediate family members, and how much he paid everybody else.

Mayor Vauss: No. To be honest, that’s not my concern. We paid to have these artists perform at this time. The artists come and they perform. We got what we paid for.

OSC: Okay. How did you determine that the amount of the contract was reasonable?

. . .

Mayor Vauss: Based upon the money that we had at the time. So we got 168,000—the thought process is well, who can we get for 168,000 dollars to make this a successful contract?

In its response to this Report and in its lawsuit against OSC, the Township for the first time provided an estimated “breakdown of the cost ranges for the music artists” who performed at the 2023 and 2024 concerts by citing publicly-available information on the artists’ typical fee ranges that amount to more than the Township paid to the Taj vendors. But publicly-available information on the artists’ typical fee range does not explain how much Richardson and his affiliated businesses actually paid the artists and kept for themselves. The Township has no record of how much of the funds went to any of the artists, including Richardson and his son—whom the Township promoted as performers, with their images and stage names featured on flyers.[18] For his part, Richardson claims that he did not charge a fee for the DJ sets he performed at the concerts and did not know whether the Taj vendors profited from the events, and Green-Richardson claims that her son did not charge a fee for the DJ sets he performed.

But Green-Richardson confirmed that the businesses profited from the Opioid Awareness Day concerts and refused to disclose the amount, insisting that “most” of the money went to the artists. She and her son have also refused to comply with OSC’s subpoenas for the Taj vendors’ business records. She told OSC that they do not charge a standard amount or percentage for contracts, but they often profit between $10,000 and $80,000, depending on the contract. Green-Richardson said that she did not provide itemized invoices to the Township and refused to explain to OSC how the businesses spent the money for the opioid concerts, claiming that doing so could harm the artists’ bargaining power for other contracts.

Moreover, the Mayor’s responses indicate that when evaluating whether the payments were reasonable, the Township’s only relevant question was how much opioid money it had on hand. The fact that the Township designed these events primarily around the available opioid funds underscores that the expenditures were improper. The Township had no way to assess whether costs were reasonable or how vendors used the funds, demonstrating a complete disregard for the intent of the settlement agreements.

B. The Township Paid $368,500 in Opioid Settlement Funds to Businesses Owned by Township Employee Antoine Richardson or his Immediate Family

1. Richardson was Employed as a Full-Time DJ Under the Title “Keyboarding Clerk I” Without a Clear Job Description

Of the $632,502.16 the Township spent on the 2023 and 2024 Opioid Awareness Day concerts, it paid $368,500 to two businesses nominally owned by immediate family members of Township employee Antoine Richardson.

Richardson has performed on local radio since at least 1998, and is well-known in Irvington. Multiple officials told OSC he is “very popular” locally. His radio station’s website states that “DJ Qua has worked with some very prominent politicians . . . Mayors of Newark, Irvington, East Orange, Orange, Roselle, Hillside & Jersey City to NJ Assemblyman, Senators, Congressmen and Governors.” Mayor Vauss, elected in 2014, has known Richardson since high school and recalls him DJing even then. The Mayor also said Richardson has DJ’d at some of his campaign events.

Richardson was hired as a temporary employee on July 29, 2014, and as a full-time employee with the Recreation Department on November 3, 2014. Although hired four weeks after the Mayor’s first term began, the Mayor told OSC he was not involved in the hiring. Richardson said that he was not sure who from the Township ultimately interviewed or hired him. The BA said the department director would have decided, and the BA “would have just signed off.”

But the Recreation Director at the time, employed since 1998, told OSC he did not hire Richardson. He said he “did not ask . . . but then, you know, new administration comes in . . . if they had anybody that wanted to work, that’s their prerogative.” Richardson was not hired for a specific task—after assignment, the Director integrated him into the team. Richardson worked 6.5 hours daily, Monday through Friday, greeting visitors, helping run programs, and inspecting parks. During his time in the Parks & Recreation Department, Richardson was required to keep his time by punching in and out on a timeclock.

Richardson was disciplined for attendance issues. In September 2015, the BA issued a written reprimand for failing to punch in and out, which should have resulted in six days’ loss of pay. Another reprimand in November 2016 reminded him to follow timeclock policies, warning of further discipline. A 2016 evaluation noted “attendance needs . . . improvement,” and a 2017 evaluation said he did “not abuse sick, or personal time,” but again cited attendance issues. The Director said Richardson’s attendance improved afterward, but in early 2018, the Director stopped seeing Richardson at work. After a week, he called Human Resources, which advised that Richardson no longer worked in Recreation. The Director was not told why.

The Township and Richardson provided different explanations for the change in Richardson’s job. The BA told OSC he transferred Richardson in approximately 2018 because he had not realized until reprimanding Richardson that he was the same radio DJ the BA was familiar with. The BA thought Richardson’s DJ talents were being “squandered” in Recreation and the Township needed sound services for events. By contrast, Richardson told OSC that the Township moved him from Recreation to his new role after he told multiple Township officials, including the BA, that he was feeling “overwhelmed” by the amount of people asking to take pictures with him due to his celebrity status. Either way, in 2018, Richardson’s full-time job became providing sound and music services for Township events. He remained on the Recreation Department’s payroll but was “technically” supervised by the BA.

Although Richardson was reassigned to the BA’s supervision over seven years ago, the Township never created a formal job description or updated his civil service title to reflect his actual responsibilities. The Township has no official criteria for evaluating Richardson’s performance in his current role. His personnel file contains performance evaluations from his time in Recreation, but none since 2018. According to the Township, his Civil Service Commission (CSC) title is “Keyboarding Clerk I,” a clerical designation focused on document processing and data entry—which bears no resemblance to the work he actually performs.

In contrast, the BA described Richardson’s actual responsibilities as preparing and operating audio equipment, providing music and amplified sound, attending “rehearsals,” and DJing at up to twenty Township events per year. Richardson also transports, repairs, and replaces equipment at his own expense and promotes events on his radio show, which the BA called an “added benefit.” The BA admitted the lack of evaluations is a “failing” but claimed to monitor performance through event attendance. Richardson described his job duties as providing “all PA” services—“any audio, or any entertainment”—for all Township departments on an as-needed basis. Although classified as an employee, Richardson’s independent, unsupervised role—using his own equipment and controlling his work—makes him more like an independent contractor. Under state law, he would likely qualify as one if not for his salary, benefits, and pension.[19]

The disconnect between Richardson’s title and actual duties—combined with the Township’s lack of oversight—created conditions ripe for further accountability failures and conflicts of interest.

2. Richardson has a Financial Interest in Two Vendors Hired for Multiple Township Events, Including the Opioid Concerts

The Township’s frequent hiring of vendors owned by Richardson or his immediate family to perform services overlapping with his full-time responsibilities created a clear conflict of interest.

In 2023, the Township awarded $168,500 to Taj Lounge 973, LLC (Taj Lounge). Records filed with the Division of Revenue and Enterprise Services (DORES) show Taj Lounge was formed in June 2019 for “music hosting” and “night club hosting,” with Antoine Richardson as its sole member. By 2023, its Certificate of Formation listed Green-Richardson as sole member. She explained that Richardson turned over the business to her because they wanted to obtain a liquor license and could not do so while the business was owned under Richardson’s name.

In 2024, the Township awarded $200,000 to Taj Entertainment LLC (Taj Entertainment), formed July 2022 with Richardson’s son, as sole member. Richardson’s son has not cooperated with a subpoena and court order for his sworn statement. Green-Richardson explained that she helped her son create Taj Entertainment, but that “When we say Taj Entertainment, Taj Lounge—that’s all us,” referring to her husband, her son, and herself.

After OSC raised concerns on May 21, 2024, the Township responded in its May 29, 2024 letter that “Richardson, a recreation employee, does not own Taj Entertainment or Taj Lounge but is a family member,” claiming no conflict.

This reply is problematic in two ways. First, the Township understood it was effectively hiring Antoine Richardson himself for his ability to retain artists, even if he did not own the businesses on paper. The Mayor told OSC he worked directly with Richardson to determine which artists the Township could afford and understood Richardson was securing the artists. The Township’s position that there was no conflict because the businesses were nominally owned by family contradicts its justification for using the EUS exception, which relies on Antoine Richardson’s supposedly unique access to highly desired artists.

Second, even assuming Richardson was not the real owner of the businesses, the Township promoted him (“DJ Qua”) as a performer, with his image and stage name featured on flyers alongside his son’s.[20] In his lawsuit against OSC, the BA claimed in his signed certification that Richardson “served only as an unpaid MC at the concert” and “received no compensation beyond his regular Township salary.” But Green-Richardson confirmed that the Taj vendors profited from these contracts, and Richardson has access to the bank accounts where business’s earnings are deposited. This also conflicts with the Mayor’s statement that he did not know or care whether Richardson was compensated and with the Township’s own inability to verify how the funds paid to the Taj vendors were ultimately used. Green-Richardson insisted the profits were “small” but refused to disclose the amount. She has also refused to comply with OSC’s subpoenas for business records from the Taj vendors.

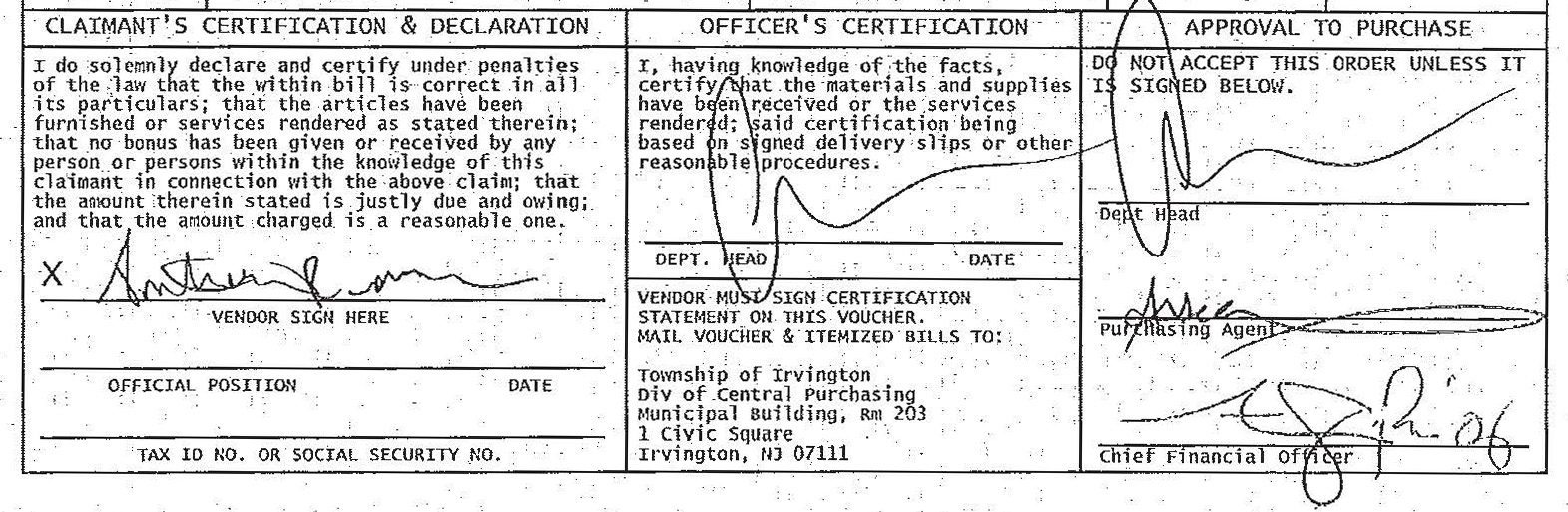

The BA also claimed in his certification that “Richardson did not participate in the procurement or contracting process.” But Township records, Green-Richardson, and Richardson himself directly contradict that statement. Richardson, not his family members, communicated with officials, signed purchase orders, and picked up payments for the 2023 and 2024 concerts on behalf of the Taj businesses. Emails and texts between the QPA and Richardson show he submitted forms for both events. Richardson identified his own signature on (1) the agreement between Taj Lounge and the Township for the 2023 concert; (2) the purchase orders for the 2023 and 2024 concerts; (3) the Jan. 8, 2024 proposal submitted to the Township on behalf of “Taj Entertainment”; (4) the $168,500 check issued by the Township to Taj Lounge in 2023; and (5) the $100,000 check issued to Taj Entertainment in 2024.[21]

Figure 14: Check Issued to Taj Entertainment for 2024 Event and Signed by Antoine Richardson

Richardson described Taj Lounge as a “family business,” and said that because his wife started Taj Lounge based off of his own relationships with artists, “my wife is me.” And if there were any further doubt as to who actually participated in the procurement process with the Township, neither the QPA, BA, nor Mayor knew Trennetha Green-Richardson, the nominal owner of Taj Lounge.

The Township’s argument in its May 29, 2024 letter also conflicts with its own Purchasing Manual and local ordinance,[22] both of which prohibit employees from having a direct or indirect interest in Township contracts. OSC raised conflict concerns on January 31, 2024; seven days later, the Township updated its Purchasing Manual to prohibit Township employees from being “interested directly or indirectly” in Township contracts—just 13 days after awarding the $200,000 contract to Taj Entertainment. Yet in May—four months after updating its Purchasing Manual—the Township claimed there was no conflict because Richardson’s family members were the nominal owners of the Taj businesses, and stated “based on the OSC’s recommendation, we will update our Purchasing handbook.”

The Township also claimed in its letter that its ordinance “in Article I, Section 7-4, prevents conflicts of interest concerning utility-related contracts but not all service contracts.” This misreads the plain language of the ordinance, which broadly prohibits all employees and officers from having direct or indirect interests in Township contracts and imposes additional restrictions on public utility contracts. The ordinance has been in effect since at least 1981. The QPA told OSC she understood it to prohibit awarding contracts to employees. Still, the BA admitted the Township has violated the ordinance repeatedly—”we’ve done business with Township employees previously . . . It’s just not unusual.”

The Township has since taken remedial steps that undercut its claim that these arrangements were appropriate. On June 15, 2024, it added a vendor certification form to its standard bid package, requiring vendors to declare that no Township employee or immediate family member has an interest. It also updated its employee handbook to require disclosure of familial relationships in public bids and allow disqualification if the Township Attorney deems a conflict exists. These updates are positive, but they also acknowledge the inherent conflict in the Taj contracts, even as officials continue to deny it.

The Township failed to apply its own conflict of interest rules to Richardson and others, despite longstanding policies and recent updates that acknowledge such arrangements are unethical.

C. The Township Relies on an “Honor System” for Verifying Richardson’s Work Hours and Performance Despite his Dual Role as Vendor and Township Employee for Identical Services

The Township’s repeated use of vendors owned or controlled by employee Richardson or his family reflects a clear conflict of interest and raises concerns about double compensation for work that overlaps substantially with his full-time duties. Officially a “Keyboarding Clerk I,” Richardson in practice serves as a DJ and event technician—roles for which the Township also pays vendors linked to him. The Township could not account for how much, if any, of the 2023-2024 opioid event funding went to Richardson through these vendors, nor explain a 19 percent increase in vendor payments from 2023 to 2024. Despite these concerns, the Mayor expressed no interest in verifying how much was paid or to whom:

We got several artists . . . If [the Taj vendors] didn’t bring the artists, we’ve got a problem. They’re in violation of the contract. We got the artists, the artists performed, the people were happy, we saved some lives. That’s what it was. But no money went to [Richardson].

When asked how he knew that Richardson did not receive opioid funds, the Mayor responded:

Because the artists performed. Unless they performed for free and he kept all the money—I could care less. Because they performed.