A Brief History of the Delaware and Raritan Canal

.jpg) |

The idea to construct a canal across the narrow "waist" of central New Jersey, and thereby create an inland waterway that would connect the cities of Philadelphia and New York was reputed to first been proposed by William Penn, the founder of Pennsylvania, who in 1676 is purported to have ordered a surveyor to go up the Delaware River to investigate whether it was possbile to have "...a way cut across the country to Sandy Hook." No evidence remains that such a study was ever undertaken. The idea remained dormant for the next 100 years, while the British colonies of North America grew to importance, fought for their independence, and then turned their attention to constructing internal improvements for their vast and sparsely populated nation.

During the early part of the nineteenth century, New Jersey’s public passion for a canal to connect New York and Philadelphia became intense, and the Legislature tried on several occasions to establish a canal through the central part of the State. The greatest obstacle to the venture build a canal was the equally intense passion for railroad building. Each of these factions was able to prevent the success of the other in the Legislature. In 1830 the Legislature granted simultaneous charters to a canal company and to a railroad company to traverse central New Jersey. A year later a legislative compromise was reached to pool the stock of both companies and charter a canal-railraod partnership, forming the Delaware and Raritan Canal Company and the Camden and Amboy Railroad and Transportation Company -- known thereafter as the “Joint Companies.”

Both railroad and canal began construction in the fall of 1830. By September, 1833, the railroad was in operation over its entire line between Bordentown and South Amboy. While the section of the canal from Trenton to Kingston was opened at about the same time, it was not until the following year that the entire canal was opened. The official opening of the canal took place on June 25, 1834, when Governor Peter Dumont Vroom and other dignitaries began a two-day trip on the canal. The Governor’s barge was met by cheering crowds at every lock, bridge, and basin along the route. They received a 24-gun salute when they arrived in New Brunswick; then Governor Vroom, his party and a brass band paraded through the city.

The canal's path across the State cut a large meandering letter “Y.” The main canal comes out to the Delaware River just north of Bordentown. From there it runs 44 miles through central New Jersey before it empties into the Raritan River in New Brunswick. The Bordentown location was chosen because north of this site the Delaware freezes earlier and stays frozen longer. New Brunswick was selected for the outlet because the head of navigation of the Raritan River is located in that city. Ocean-going vessels could sail up the Raritan to New Brunswick and exchange cargo with the canal barges. A 22-mile long "feeder" canal was built to supply water to the main canal. The feeder comes out of the Delaware River at Raven Rock in Delaware Township and runs next to the river southward to Trenton where it joins the main canal.

The engineering of the canal proved to have been excellent; during the 100 years it was in operation very few changes were made in the waterway. The feeder was built to be 6 feet deep and 50 feet wide, while the main canal was 7 feet deep and 75 feet wide. Water entered the feeder at an elevation of 70 feet above sea level. The main canal climbed through seven locks before it got to Trenton and then descended through seven more locks before reaching sea level at the Raritan River. The banks were "rip-rapped" with stone so that vessels could move at a reasonable speed without washing the banks into the canal. All of canal’s bridges were "swing bridges" that pivoted horizontally so that vessels of any mast height could go through the canal. The locks were operated by steam powered winches and valves after 1868.

|

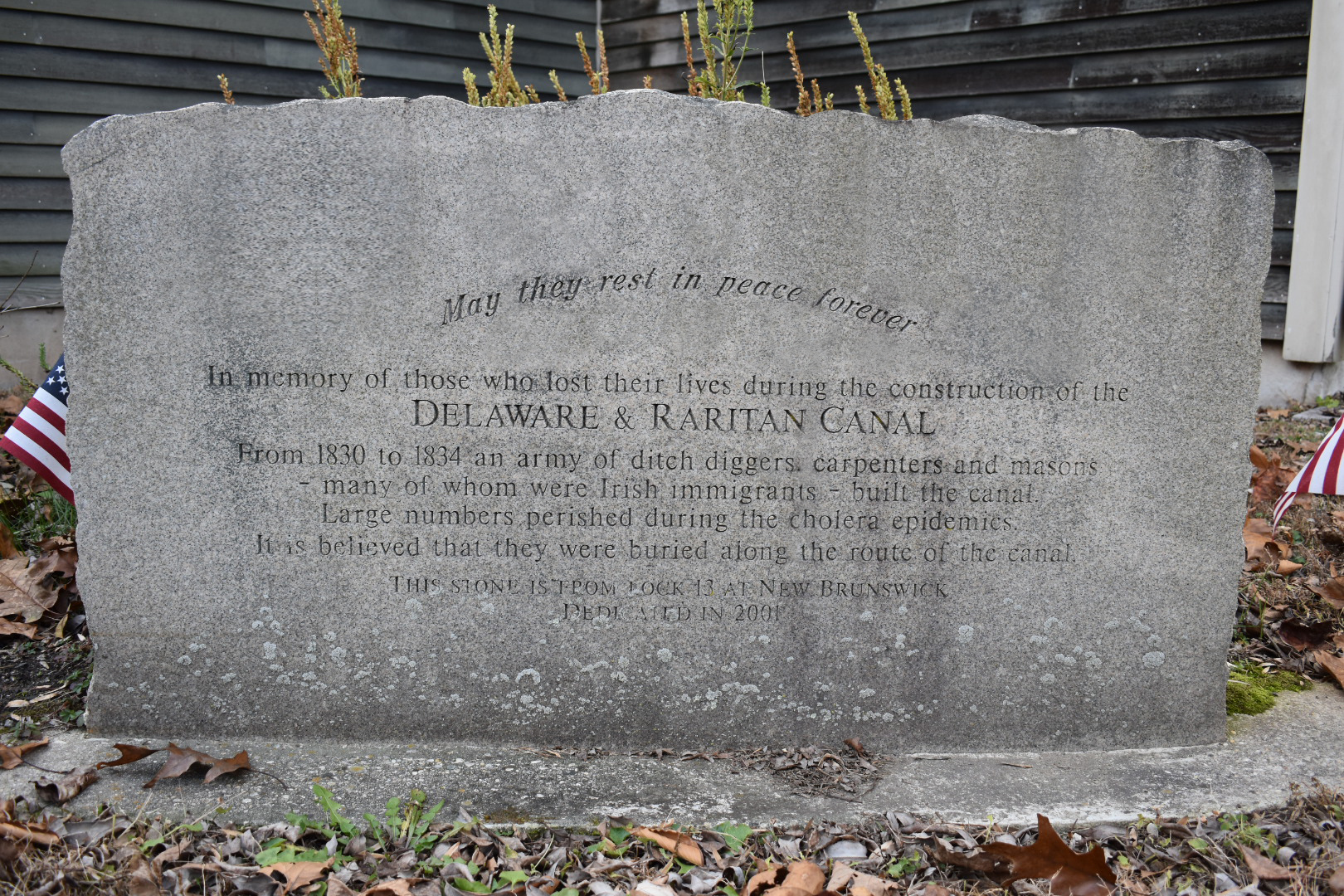

The cost of construction is estimated to have been approximately $2.83 million; a modest expense even by standards of the 1830s when one calculates the return made on that investment. There was, however, another cost that cannot be calculated. The canal was largely dug by hand by Irish immigrants. Scores of these workers died when so-called "Asiatic" cholera swept through the labor camps in 1832. The workers were buried in unmarked mass graves on Bull’s Island, at Ten Mile Run, and at Griggstown. A granite monument taken from a lock in the New Brunswick section of the canal was dedicated to their memory at the Bull’s Island Recreation Area on St. Patrick’s Day in 2003.

Canal purists insist that the feeder cannot truly be called a canal because it was built as a water conduit and not as a waterway for boats. However, the feeder was navigable by canal boats from the time it was built until 1913. Traffic on the feeder greatly increased after changes were made in the 1840s which allowed boats to enter at Lambertville. Coal barges coming down Pennsylvania's Delaware Canal from the Lehigh Valley were locked out of the Pennsylvania canal at New Hope, crossed the Delaware River on the cable propelled by the current of the river, and were locked into the feeder canal at Lambertville. Major engineering changes were made in the 1850s when the locks were made longer, the depth of the main canal was increased to 8 feet, and stone rip-rapping was installed to stop erosion of the canal’s banks.

It took the better part of two days to travel from Bordentown to New Brunswick using the canal with the most frequent stopover point being at Kingston. This two-day trip was an improvement over the usual time of two weeks for water travel going from Philadelphia to New York usng the Atlantic Ocean route. It is difficult to assess the impact of the canal on the State. Trenton and New Brunswick clearly benefited from its presence because they became regional centers for the transfer of goods between wagons and trains and canal barges. Trenton witnessed an industrial boom shortly after the canal was opened; her population increased four-fold within a few years, and ironworks, ceramic factories, and many other businesses came during this period. It is harder to determine, however, the impact of the canal on communities between the termini. Some farm products or locally produced goods were transported by canal, but since the canal went through the narrowest part of New Jersey, few farmers had access to it. The small communities along the route, such as Rocky Hill, Griggstown, and East Millstone, must have received some impetus from the canal, but they did not and still have not become major regional centers. The most obvious benefit from the canal was derived by New York and Pennsylvania because it was their commerce -- mostly Pennsylvania anthracite coal destined for New York industruial furnaces and homes -- that was the chief commodity that was transported through the canal.

The Civil War and the industrial expansion that followed the war caused the 1860s and 1870s proved to be the most successful years for the Delaware and Raritan Canal. The record year was in 1871 when 2.99 million tons (80% of which was coal) were shipped through the canal. The total tonnage for that year was more than was carried in any single year on the much longer and more famous Erie Canal. However, another important event occurred in 1871. The Pennsylvania Railroad Company took a 999-year lease on both the canal and the Camden and Amboy rail connection across the center of the State. From this time on the canal showed a steady decline. By 1893 the canal showed a net loss in its operations, and it was never operated profitably again. There were a number of reasons for the decline, but the most important of them was that other railroad lines began to open in this area.

In 1876, the Reading Railroad expanded its lines though Central Jersey, and in 1893 the Pennsylvania Railroad also opened another line. The canal was simply not able to effectively compete against the railroads, which were faster, less expensive, operated day and night, and did not close for the winter. Historians and other observers of the canal's history also believe that there is merit in the charge that the Pennsylvania Railroad deliberately killed the canal, through infrequent repairs and by imposing higher rates on canal users for transporting the same products that received simultaneous reductions when transported by rail.

|

In 1932-1933 the canal closed for the winter, as it did each year. However, it did not open in the spring of 1933. The charter to the Joint Companies called for forfeiture to the State for failure to operate the canal for three consecutive years. Thus in 1937, with 933 years left on its lease, the Pennsylvania Railroad turned the Delaware and Raritan Canal over to the State of New Jersey.

The canal had lasted 99 years before it was believed to be obsolete. It had witnessed an important part of New Jersey history and hosted a wide variety of vessels. There were two classes of barges in most common use. Those from the Pennsylvania Canal were 90 feet by 10.5 feet wide and drew 5.5 feet of water when loaded. The river boats from the Hudson and Erie Canals were 100 feet long by 17.5 feet wide and drew 7 feet of water when loaded. Most of the barges were mule-driven, but the country’s first use of steam tugs on canals was on the Delaware and Raritan Canal in the 1840s.

One of the most interesting aspects of the Delaware and Raritan Canal was the large variety of boats that passed through it. In addition to mule-towed canal boats, sail boats, steam tugs towing barges, freight boats, millionaires’ yachts and naval vessels all used the canal. Canal boats from most canals on the east coast traversed the canal at some time. When the canal was opened it was believed that there would be a thriving business in passenger service, but the canal ultimately could not compete with the speedier railroads for passengers and this service was abandoned within two years.

|

After the State took possession of the canal, several studies were undertaken to decide what should be done with it. The studies determined that it would have been too expensive to fill the canal or to renovate it just for recreation boating; that the canal could not be expected to be profitable as a freight waterway; and that potable water was easily obtained from other sources. However, during the late 1930s, industries started to move out of cities, and sites near the canal were popular relocation spots due to central New Jersey's excellent railroad and road systems. These industries needed water, and the canal’s water could be furnished cheaper than water provided from wells. Consequently, the Delaware and Raritan Canal, which could no longer make a profit by transporting boats on its water, made a profit from selling the water itself.

In 1936, the Trenton portion of the main canal was deeded to that city and filled to construct the Route 1 "Trenton Freeway" as a Works Progress Administration project. The portion of the main canal in Hamilton Township in the area of Duck Island was thereafter cut off from the rest of the canal and abandoned. Rehabilitation of the remainder of the canal as a water transmission complex was started in 1944 under the supervision of the Division of Water Resources in what is now the Department of Environmental Protection. Three wooden aqueducts, which carried the canal over streams, were replaced with concrete structures. Wooden gates at Raven Rock, Kingston, and New Brunswick were replaced with concrete headwalls with steel sluice gates. The canal was also dredged and flumed in several areas to improve the flow of water.

In 1973, the Delaware and Raritan Canal and 17 related canal structures relating were placed on the National Register of Historic Places. A year later, in response to groups of concerned citizens and following the recommendation of a study commission headed by Senator Raymond H. Bateman of Somerset County, the Legislature passed an act which established the Delaware and Raritan Canal State Park.

Today, the Delaware and Raritan Canal is a great asset to the State of New Jersey. The Delaware and Raritan Canal Park was visited by an estimated 1.2 million people in 2017. The park enhances several urban communnities and provides a corridor for conservation and recreation through the densely-populated central New Jersey region. It is not only an historic site itself, but it links together many other sites that are significant in the Garden State’s development. The canal is an easily-accessible recreation area that provides water to industry, agriculture and drinking water to approximately one million residents of central New Jersey.

Official Site of The State of New Jersey

Official Site of The State of New Jersey