Public Access Maps

Public Access Listserv

Frequently Asked Questions

Contact Us

Coastal Management Home

|

|

NJ Public Access Rights>History and Legal Precedents

History and Legal Precedents

The public rights of access to and use of the tidal waterways and their shores are based in the common law rule of the Public Trust Doctrine, first codified by the Roman Emperor Justinian around 500 AD as civil law. It establishes the public’s right to full use of the seashore. The current rule stems from this but has been modified by legal decisions and recent implementation policies.

Legal Background

Public Access in New Jersey: the Public Trust Doctrine and Practical Steps to Enhance Public Access provides an indepth review of the history and legal precedents of public access. It was prepared in 2006 by the Coastal Management Office of the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection, and Principal Investigator: Robert Freudenberg – NOAA Coastal Management Fellow 2004-2006.

NJ Department of Environmental Protection, Coastal Management Office, Public Access in New Jersey: the Public Trust Doctrine and Practical Steps to Enhance Public Access, by RobertFreudenberg, Trenton, NJ, 2006, www.nj.gov/dep/cmp/access/public_access_handbook.pdf

Section II: Legal Background

- The Public Trust Doctrine

- History

- Lands and Waters Subject to Public Trust Rights

- Public Rights under the Public Trust Doctrine

- Court Cases

- State Implementation of Public Access

- Private Property Rights

Appendix A

Section II: Legal Background

In order to fully understand public access and the government roles and responsibilities, it is important to consider the legal background on the Public Trust Doctrine, the state’s authority to implement it and the rights of the public and private property owners.

- The Public Trust Doctrine

- History

Public rights of access to and use of the tidal waterways and their shores, including the ocean, bays, and tidal rivers, in the United States predate the founding of this country. The rights are based in the common law rule of the Public Trust Doctrine. First codified by the Roman Emperor Justinian around 500 AD as part of Roman civil law, the Public Trust Doctrine establishes the public’s right to full use of the seashore as declared in the following quotation from Book II of the Institutes of Justinian:

“By the law of nature these things are common to all mankind – the air, running water, the sea, and consequently the shores of the sea. No one, therefore, is forbidden to approach the seashore, provided that he respects habitations, monuments, and the buildings, which are not, like the sea, subject only to the law of nations.”

Influenced by Roman civil law, the tenets of public trust were maintained through English Common Law and adopted by the original 13 colonies, each in their own form. The grants that form the basis of the titles to private property in New Jersey never conveyed those public trust rights, which were reserved to the Crown. Following the American Revolution, the royal rights to tidal waterways and their shores were vested in the 13 new states, then each subsequent state, and have remained a part of law and public policy into the present time. Tidal waterways and their shores always were, and remain, subject to and impressed with these public trust rights.

- Lands and Waters Subject to Public Trust Rights

In the United States, lands and waters subject to public trust rights are generally tidal waterways to either the ordinary high water line or the ordinary low water line and those lands that are beneath them. States that mark the boundary at the ordinary high water line are considered “high water states,” while those that mark the boundary at the ordinary low water line are considered “low water states.” New Jersey is a high water state and it further clarifies that the upland boundary of lands owned by the state is the Mean High Water (MHW) or the mean high tide line (See Figure 3). MHW is a tidal datum that is the arithmetic average of the high water heights observed over a specific 18.6-year water Metonic Cycle. This line has been established for the entire New Jersey coastline. All lands and waters extending seaward of the MHW line are held in trust by the state on behalf of the public. The rights of the public are vested in the state as owner and trustee. These publicly owned lands include tidelands, shores of tidal rivers and streams, the land beneath oceans and tidal rivers and streams (submerged lands) and filled lands formerly flowed by the tide. As the Public Trust Doctrine has evolved over the years, courts have ruled that the dry sand areas landward of the MHW line are also subject to certain public rights under the Pubic Trust Doctrine, as needed for enjoyment of the tidal waterways and lands below the MHW line.

- Tidelands

Tidelands, also referred to as riparian lands, are all those lands now or formerly flowed by the tide in a natural waterway (see Figure 3), including filled lands. In New Jersey, tidelands are held in trust by the state for the public unless these lands have been conveyed to other uses. Even when the state conveys tidelands to private ownership, they do not convey the public trust interest in the lands (See Section c). The upper boundary of tidelands is the mean high water line and all lands seaward of this line are subject to the Public Trust Doctrine and are to be administered by the state in the public interest.

- Submerged Lands

Submerged lands are those lands that are situated below the mean low water line. They include the lands beneath the sea, tidal rivers and bays. In 1953, the US Submerged Lands Act (43 U.S.C. 1301-1315) affirmed state ownership and control of submerged lands extending from the coastline out to three geographical miles. In New Jersey, submerged lands are considered the same as tidelands and are subject to public trust rights and duties under state law.

- jus publicum, jus privatum – Special Property Titles

Unlike most property titles, the title to lands subject to public trust rights is not singular, due to the special and public nature of these lands. Instead, lands subject to public trust rights are vested with two co-existing titles, one dominant and the other subservient. The jus publicum is the dominant title and can be described as the bundle of trust rights granted to the public to fully use and enjoy these lands and waters for commerce, navigation, fishing, bathing and other related public purposes. These public rights are vested in the state as

owner and trustee of lands subject to public trust rights. The subservient title, jus privatum, represents the private property rights that may exist in the use and possession of lands subject to public trust rights. The courts often cite the important distinction between these two titles when defining a state’s authority to convey lands subject to public trust rights to private ownership, and when describing the public rights remaining in these lands that have been so conveyed. In New Jersey, the upland owner’s boundary is the mean high water line. Below that line, the state is the “fee simple absolute” owner of this land, owning both the private (jus privatum) and the public (jus publicum) titles, as trustee for the public. So, in the case of an ocean beach, the state holds both titles regardless of whether or not there is a private landowner upland of the mean high water line. A state can convey its jus privatum interest into private property ownership, but can never convey the jus publicum interest nor relinquish its trust responsibilities. This leads to a scenario in which a private property owner can be in possession of lands which the state is the trustee of certain public rights of access to and use of under the Public Trust Doctrine. Because the jus publicum title is dominant, a private property owner may not legally prevent the public from using lands below the mean high water line.

- Dry Sand Areas

New Jersey Supreme Court Cases have held that various stretches of dry sand areas above the mean high water line are subject to certain rights of access to and use by the public, in order to fully enjoy lands subject to public trust rights. The amount of dry sand will vary depending on a consideration of factors established in the NJ Supreme Court Case Matthews v. Bay Head Improvement Association, 95 N.J. 306 (1984). Factors to be considered when determining the amount of dry sand available for public use include:

- location of the dry sand area in relation to the foreshore

- extent and availability of surrounding publicly-owned upland sand area

- nature and extent of the public demand

- usage of the upland sand by the owner

- Public Rights under the Public Trust Doctrine

The Pubic Trust Doctrine provides that public rights to tidal waterways and their shores in the state are held by the state in trust for the benefit of all of the people. Further, it establishes the right of the public to fully utilize these lands and waters for a variety of public activities. While the original purpose of the Public Trust Doctrine was to assure public access for navigation, commerce and fishing, in the past two centuries, state and federal courts have recognized that modern uses of tidal waterways and their shores are also protected by the Public Trust Doctrine. In New Jersey, the Public Trust Doctrine recognizes

and protects natural resources as well as recreational uses such as bathing swimming, sunbathing, and walking along tidal waterways and their shores.

- Public Access and Use

As the trustee of public rights to tidal waterways and their shores, it is the duty of the state to not only allow and protect the public’s right to use them, but also to ensure that there is adequate access to these sites. Access ensured by the Public Trust Doctrine can be classified into different types, including:

- Perpendicular Access

- Visual access

- Linear/Lateral Access

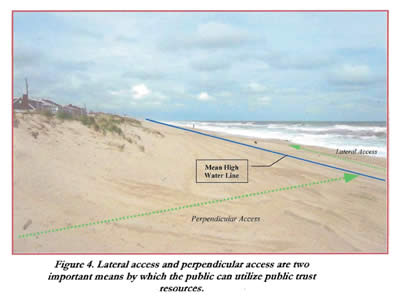

Linear or lateral access refers to access along tidal waterways and their shores, which are subject to trust for the public (see Figure 4). Under the Public Trust Doctrine and the rulings of cases that have enunciated it, the public has the right to use tidal waterways and their shores for activities including fishing, swimming, boating, walking and sunbathing. In addition, the public has the right of access to and use of a reasonable amount of the dry sand area landward of the MHW line at beaches according to the factors set forth in the NJ Supreme Court case Matthews v. Bay Head Improvement Association, 95 N.J. 306 (1984) and listed above, as well as along the Hudson River as upheld by the Federal District Court in National Association of Home Builders v. NJDEP, 64 F. Supp. 2d (D. NJ 1999). An example of linear or lateral access is the ability to take a walk on a beach along the shoreline. Because of the public trust nature of these lands, anyone should be allowed to walk uninhibited within this area and free of charge.

- Perpendicular Access

Perpendicular access refers to the ability of the public to reach tidal waterways and their shores by corridors across land that may or may not be publicly or privately owned (see Figure 4). Examples include street ends that abut beaches or other shorelines, public access easements across private property, dune walkovers and trails or walkways that lead to tidal waterways and their shores. Without the ability to reach the tidal waterways and their shores via perpendicular access, rights provided by the Public Trust Doctrine are essentially lost to the public, exemplifying the importance of this type of access. It is up to the state and local governments to ensure that this access is provided and preserved.

- Visual Access

Through decisions in cases such as Hartz Mountain Industries, Inc. v. DEP (See In RE Waterfront Dev. Permit No-WD88-0443-1, 244 NJ Super. 426, 429-430 (App. Div. 1990), the courts have recognized that the scope of public access includes rights of visual access. Visual access is the ability of the public to have access to views of coastal resources without these views being unreasonably obstructed. As development along shorelines continues, there is a tendency to build in ways that provide the maximum benefit of views to those on the developed site, often at the expense of the public. In the Hartz Mountain Industries case and its subsequent settlement agreement, it was decided that two 16-story towers proposed to be built along the Hudson River with views of the river and New York City skyline, should be moved to accommodate the views of the public. Additionally, a scenic easement was secured that preserves the view in perpetuity, ensuring the right of visual access.

- Site Conditions

While they do not always include specific types of access, reasonable, convenient and safe conditions at or around public access areas and public accessways often affect whether the public will be able to reach and use tidal waterways and their shores. Such site conditions include informative signs marking public accessways, the absence of threatening or misleading signs, adequate facilities (including restrooms) within a reasonable distance of tidal waterways and their shores and sufficient parking located near public accessways. Additionally, special measures, such as ramps installed in accordance with the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), can be taken as appropriate to ensure that coastal lands and waters are accessible by all members of the public.

- Public Property Rights and Conservation Restrictions

As discussed above, affording the public the opportunity to reach coastal lands and waters via perpendicular access cannot be ignored. It is possible for the public to enjoy such rights of passage over particular parcels of property without full public ownership of them. This is accomplished through the use of a conservation restriction which is a legally binding agreement that limits certain types of uses, while allowing others (such as a public walkway), to take place on a piece of property, now and into the future. An easement is a commonly used type of conservation restriction. Conservation restrictions may be acquired through eminent domain, an agreed purchase or through dedication. Conservation restrictions may also be required as a condition of certain land use permits granted for development or for shore protection projects. For example, a coastal developer may be required to set aside a parcel of property for public access, to ensure preservation of public trust rights. Under the terms of a “conservation restriction,” (the most commonly used easement for public access purposes) a property owner allows use of a portion of their land in exchange for the assurance that the land will only be utilized in a specific, agreed upon manner. Conservation restrictions are required as a condition of many coastal development permits granted by the department and are recorded under the New Jersey Conservation Restriction and Historic Preservation Restriction Act (N.J.S.A. 13:8B-1 et. seq.). Conservation restrictions maintain areas dedicated for public access in perpetuity.

- Court Cases

The Public Trust Doctrine is an example of common law authority that is continually developing through individual court cases. While first applied in New Jersey in an 1821 case, the past three and one-half decades have seen the legal relationship of the upland areas to the water’s edge and the Public Trust Doctrine as the subject of litigation in a number of cases, some of which have reached the New Jersey Supreme Court. Due to the increase in development and privatization of coastal upland areas, public access to the coast has become

a more contentious issue between private owners and the public, which has resulted in these lawsuits. In addition to cases involving physical barriers to access, there have been instances where municipalities and local property owner associations have attempted to limit use of recreational beaches to their citizens and members through methods designed to exclude outsiders. In the majority of these cases, New Jersey courts have ruled that these actions violate the Public Trust Doctrine, finding that lands, which should be available for the general public’s recreational use, were being appropriated for the benefit of a select few.

The following is a summary of some of the most important New Jersey court cases that have set legal precedents for establishing and maintaining public access to tidal waterways and their shores throughout the state:

Arnold v. Mundy, 6N.J.L. 1, 95 (1821)

Case Highlight: First New Jersey case to apply the Public Trust Doctrine, identifying common property as including the air, the running water, the sea, the fish, and the wild beasts " ...to be held, protected, and

regulated for the common use and benefit."

Arnold v. Mundy, was one of the first cases to recognize the existence of the Public Trust Doctrine in the United States. The case came about when the plaintiff, an owner of land next to the Raritan River, claimed private ownership of the fishing rights in its tidal oyster beds. The plaintiff bought oysters, planted them on the beds below the mean low water mark and staked them off, driving off anyone who attempted to take oysters. The defendant removed oysters from the bed and pleaded not guilty to trespassing, claiming that the location was a public navigable river, in which the tide flows and in which oysters grow naturally, and that all the citizens of the state had a common right to them. Using the legal distinction between private, public, and common property, the court rejected the landowner's claim to exclusive rights in the tidal oyster beds. In making this decision, the court relied on “the law of nature, which is the only true foundation of all the social rights.” They held that the state, in giving over the land to a private owner, “cannot make a direct and absolute grant of the waters of the state, divesting all the citizens of their common right.” Common property (property encumbered with a public trust), said Chief Justice Kirkpatrick, includes 'the air, the running water, the sea, the fish, and the wild beasts. [These are] things in which a sort of transient usufructuary possession only, can be had . . ..' Unlike other public property, it was " ... to be held, protected, and regulated for the common use and benefit."

Borough of Neptune City v. Borough of Avon-by-the-Sea, 61 N.J. 296 (1972)

Case Highlight: First New Jersey case to enunciate the Public Trust Doctrine holding that a municipality could not charge higher fees to non-residents than to residents for use of its municipally owned beaches, and recognizing that public trust rights include recreational uses.

In 1972 in the case of Borough of Neptune City v. Borough of Avon-by-the-Sea, the court was called upon to decide whether an oceanfront municipality had the right to charge higher beach access fees of non-residents than municipal residents. Residents from the borough of Neptune City, an inland municipality adjacent to the borough of Avon-by-the-Sea, brought suit challenging Avon-by-the Sea’s municipal ordinance granting the borough the authority to charge non-residents higher fees to access the municipally owned beach than its own

residents. The court recognized that the municipally-owned sand area in question had been dedicated for public beach recreational purposes and was – in effect – a public park open to all the public. They remarked that New Jersey has “always recognized the trust doctrine” and that the land between the mean high and low water marks, in addition to the land covered by the ocean, was owned by the state in fee simple and was for the common use of all people. In its analysis, the court found that it was valid for municipalities to charge reasonable fees for the use of their beaches, but not in a way that may “discriminate in any respect between their residents and non-residents.” The court decision stated: “… at least where the upland sand area is owned by a municipality – a political subdivision and creature of the state – and dedicated to public beach purposes, a modern court must take the view that the public trust doctrine dictates that the beach and the ocean waters must be open to all on equal terms and without preference and that any contrary state or municipal action is impermissible” (61 N.J. at 308-309).

Also significant, was the court’s recognition that public trust rights extend beyond traditional navigation and fishing uses to “recreational uses, including bathing, swimming and other shore activities.”

Van Ness v. Borough of Deal, 78 N.J. 174 (1978)

Case Highlight: Supreme Court reaffirms the Public Trust Doctrine and states that under the doctrine, a municipality could not set aside part of a public beach for use by residents only, even if alternative public beaches were provided.

In 1978, this case appeared before the New Jersey Supreme Court as the result of a suit brought by Stanley C. Van Ness, Public Advocate of the state of New Jersey, against the borough of Deal. In the suit, Van Ness charged the borough with “illegal and discriminatory practices in the maintenance and operation of its publicly owned beaches and facilities.” At the time, the borough of Deal owned and operated the beach along its Atlantic shoreline and divided it up into three sections. Two sections, to the north and south of the section in

question, were open to the public with no restrictions. The third section of beach was directly adjacent to a municipally owned structure known as the Deal Casino. Because the casino offered special amenities, including swimming pools, a restaurant and bathhouse, it was operated on a restricted basis offering memberships to Deal residents and property owners only. The beach adjacent to the casino was dedicated for the use of residents of Deal only, except for a 50-foot wide strip along the high water line open to the public. Fifty feet west of the high water mark, the dry sand area in front of the casino was roped off and reserved strictly for the use of casino members. The court ruled that this entire section of beach should be open to the general public, under the requirements of the Public Trust Doctrine. In taking this position, the court reaffirmed their decision in Borough of Neptune City v. Borough of Avon-by-the-Sea, 61 N.J. 296 (1972) saying that “the Public Trust Doctrine requires that the municipally owned upland sand area adjacent to the tidal waters must be open to all on equal terms and without preference.” In addition, the court stated that the borough cannot limit its dedication of use to residents of Deal, nor may it “allocate to the public on a limited basis, rights which, under the doctrine, the public inherently has in full,” even if alternative beaches were open to the public.

Matthews v. Bay Head Improvement Association, 95 N.J. 306 (1984)

Case Highlight: Supreme Court holds that the public right established by prior cases includes privately owned “quasi-public” beaches including dry sand areas “as reasonably necessary,” provided specific factors are considered.

This 1984 case involved a Borough of Point Pleasant resident who was prevented from swimming and bathing at the Borough of Bay Head beach by the Bay Head Improvement Association. This association was a nonprofit corporation whose mission was “improving and beautifying of the borough of Bay Head, New Jersey, cleaning, policing and otherwise making attractive and safe the bathing beaches…for the greater convenience, comfort and enjoyment of the residents.” They owned a majority of the beach and held the leases of the many private owners of beachfront property. To ensure that only association members or their guests were allowed to enter the beach during summer months, the association stationed beach police at the entrances where public streets lead to the beach. The court held that the association as a “quasi-public” organization – due to “its purposes, relationship with the municipality, communal characteristic, activities and virtual monopoly over the Bay Head beachfront” – paralleled the role of a municipality in its operation of the beachfront. Therefore, under the Public Trust Doctrine, the rights of private beachfront owners must give way,

to some extent, to the public’s right to have “reasonable access to the sea.” The most significant aspect of the decision was the court’s reliance on both the quasi-public nature of the association and on the unique importance of the public’s right of access to the shore, regardless of ownership. The court stated that under the Public Trust Doctrine, not only does the public have the right to use the land below the mean high water mark but also they have a right to use a portion of the upland dry sand area “…where use of dry sand is essential or reasonably necessary for enjoyment of the ocean, the doctrine warrants the public’s use of the upland dry sand area subject to an accommodation of the interests of the owner.” To help determine what is reasonably necessary, the court issued four factors to be examined including:

- location of the dry sand area in relation to the foreshore;

- extent and availability of publicly-owned upland sand area;

- nature and extent of the public demand; and

- usage of the upland sand by the owner

National Association of Home Builders v. NJDEP, 64 F. Supp. 2d 354 (D. NJ 1999)

Case Highlight: Federal District Court rules that walkway requirements included in the Hudson River Waterfront Area Rule (N.J.A.C. 7:7E-3.48) do not constitute a “taking” and are justified by the Public Trust Doctrine. Case applies Public Trust Doctrine to filled lands formerly flowed by the tide and applies Matthews factors to try to determine reasonable access.

The Hudson River Waterfront area is an 18.5-mile public access along the Hudson River between the George Washington Bridge in Bergen County and the Bayonne Bridge in Hudson County. Construction of the walkway began in the 1980s and continues today. As development along the Hudson, developers are required to construct a section of the walkway on their sites. The Hudson River Waterfront Area Rule (N.J.A.C. 7:7E-3.48) requires all owners of property within this area who desire a NJDEP waterfront development permit to comply with the following without compensation: 1) construct and maintain, at the owner’s expense, a thirty-foot wide walkway along the entire waterfront of the property, to be built to standards specified in NJDEP regulations; 2) convey to NJDEP a conservation restriction for the walkway and 3) allow perpendicular public access to the walkway. In 1998, the plaintiffs, the National Association of Home Builders and New Jersey Home Builders Associations, sought declaratory and injunctive relief alleging that the rule was unconstitutional because it constituted a taking. In addition to the NJDEP (defendants), the case included defendant intervenors including the Hudson River Walkway Conservancy, Natural Resources Defense Council, American Littoral Society, New York/New Jersey Baykeeper, Coalition for a Better Waterfront, Fund for a Better Waterfront, and Friends of Weehawken Waterfront. Both the defendants and the defendant intervenors used the Public Trust Doctrine in their argument to justify the rule and to gain access to both the filled lands along the river and the private, non-filled lands necessary to reach the walkway. The court held that property, which was once submerged beneath the Hudson River, but was subsequently filled in artificially, constituted “public trust property,” and private owners did not have the right to exclude public access. They also held that the requirement of owners to construct and maintain a public walkway and its landscaping to state standards did not constitute a taking. Further, the court determined that the four factors established in Matthews to determine the reasonableness of allowing public access to private lands are “very clear and do not include ‘individualized determinations.’” Given these factors, the court ruled that reasonableness using the Matthews factors for the non-filled land, “simply cannot be determined.”

Raleigh Ave. Beach Association v. Atlantis Beach Club, Inc., et al., 185 N.J. 40 (2005)

Case Highlight: New Jersey Supreme Court rules that private beach club cannot limit public access to its upland dry sand beach, according to the Public Trust Doctrine and by applying the Matthews factors. Also establishes that NJDEP has authority to regulate fees charged for use of beach under CAFRA.

The Atlantis Beach Club, owner of beachfront property in Lower Township, New Jersey, had allowed public access to the beach area of its property, free-of charge, prior to 1996. The beach is accessible by a pathway, approved by a 1986 DEP permit issued according to CAFRA that requires public access as a condition. In 1996, the club began limiting public access by charging seasonal membership rates that continued to increase significantly over time. The beach club became more aggressive in its public access restrictions: asking nonmembers to leave the beach, posting warning signs and finally filing an order against non-member residents to prohibit access. In response, the Raleigh Avenue Beach Association, a local resident association, filed a complaint against Atlantis and the state of New Jersey seeking access to the wet sand area and to a “sufficient amount of dry sand above the mean high water line” as granted by the Public Trust Doctrine. Reaching the New Jersey Supreme Court in 2005, the court upheld a ruling by the appellate court requiring the Atlantis property to be open to the public at a reasonable fee for services provided by the owner and approved by the DEP.

This decision builds off Matthews v. Bay Head Improvement Association, 95 N.J. 306 (1984) in its application of the public trust doctrine to a wholly privately owned upland beach. In opening the dry sand of the beach to the public, the court relied upon the factors set forth in Matthews to determine “accommodation of the interests of the owner.” Using these factors, the court held that the “Atlantis upland sand must be available for public use under the Public Trust Doctrine” highlighting the following: the longstanding access to and use of the beach; a CAFRA permit condition of public access; documented public demand; lack of publicly-owned beaches in Lower Township; and the type of use by the current owner as a business enterprise. The court also held that “the broad scope of the DEP’s authority includes jurisdiction to review fees proposed by Atlantis for use of its beach.” DEP’s authority was found to be granted under CAFRA, through the Coastal Permit Program Rules (N.J.A.C. 7:7.) and the Coastal Zone Management Rules (N.J.A.C. 7:7E). Additionally, further authority was found to be inherent in DEP’s “power to promote the health, safety, and welfare of the public.” The court did specify however, that DEP-approved fees are unrelated to the “independent and inherent right of Atlantis” to determine fees for such beach amenities as cabanas, beach chair rentals, food concessions, etc., provided all necessary permits are in place.

- State Implementation of Public Access

As part of its duty to administer tidal waterways and their shores for the benefit of the public, the state has the responsibility to ensure adequate public access to and use of New Jersey’s tidal waterways and their shores. New Jersey implements the Public Trust Doctrine and promotes access to and use of tidal waterways and their shores through regulatory action with the authority afforded by fundamental coastal laws, guided by its Coastal Zone Management rules, state statutes, and through its capital spending program. The DEP administers these laws, which include: the Coastal Area Facility Review Act (CAFRA), the Wetlands Act of 1970, the Waterfront Development Law, and the Tideland Statutes and are essential to maintaining the balance between coastal development and protecting coastal resources managed through the DEP’s Coastal Management Program. The DEP’s capital spending programs include the Shore Protection and the Green Acres programs. Short summaries of each of these are given below. (For more in depth descriptions please see Appendix A).

- CAFRA (N.J.S.A. 13:19-21)

The Coastal Area Facility Review Act (N.J.S.A. 13:19-1 through 21) authorizes the DEP to regulate and approve the location, design and construction of development within a coastal region designated as the CAFRA area. Impacts to public access are considered when granting approval or denying applications for such projects. (For more in depth description, please see Appendix A).

- Waterfront Development Law (N.J.S.A. 12:5-3)

The Waterfront Development Law addresses the impacts caused by new development proposed in and along tidal waterways. As with CAFRA, the effect on public access of the development is considered before approving the project. (For more in depth description, please see Appendix A).

- Wetlands Act of 1970 (N.J.S.A. 13:9A)

The Wetlands Act of 1970 requires the DEP to regulate development in mapped coastal wetlands and to prevent their deterioration and destruction by regulating any activities including “dredging, filling, removing or otherwise altering or polluting thereof”. Development in such a sensitive area is thoughtfully considered by the Department before granting approval, and the addition of public access must be done in such a way as to have minimal impact on the environment. (For more in depth description, please see Appendix A).

- Riparian Lands Statutes, Tidelands Act (N.J.S.A. 12:3)

Tidelands, also known as "riparian lands," are lands now or formerly flowed by the tide of a natural waterway. This includes lands that were previously flowed by the tide but have been filled and are no longer flowed by the tide. These lands are owned by the state of New Jersey and held in trust for the public. Because of their special nature, tidelands are stringently managed and in some cases the state may enter into agreement with a private owner to convey to them use of the land. To use the land, the private owner must first get permission from the state in the form of a tidelands license, lease or grant, and then pay for this use. Such a lease will often include specific requirements, one of which is the ability for the public to use a parcel of the property to gain access to the coast. (For more in depth description, please see Appendix A).

- Coastal Zone Management Regulations (N.J.A.C. 7:7E)

In an effort to improve the DEP’s coastal decision-making process by providing predictability, numerous coastal policies have been adopted as administrative rules, called the Coastal Zone Management rules (CZM rules).

These rules not only serve as the substantive core of the DEP’s Coastal Management Program but they also ensure the enforceability of the coastal laws, including the four described above. By serving as the guiding principle of the state’s coastal laws and as the basis for all state coastal permit decisions, the CZM rules help to add clarity to coastal decisions made in New Jersey. The rules set clearly defined and strict standards for public access to guide development in the coastal zone. Among these standards is the requirement to provide perpendicular and linear access to tidal waters and their shores and to allow use of these lands and waters.

According to these rules, each development proposal along a tidal waterway must address standards related to access including reasonable fees for access, providing adequate parking and facilities, and clearly marking public access locations. CZM rules, in particular the Hudson River Waterfront Area rule (N.J.A.C. 7:7E-3.48) contain standards specific to the Hudson River Waterfront Area. This rule sets forth standards for public access and open space along the Hudson River Waterfront Area, and requires development, maintenance, and management of a section of the Hudson River Waterfront Walkway coexisting with the shoreline of the development property.

- State Capital Spending Programs

New Jersey’s capital spending programs include its land acquisition program within the Department’s Green Acres program and its Shore Protection program within the Office of Engineering and Construction. Because federal, state and municipal funds are used to support the projects of each of these programs, requirements of public access are built into their agreements. This contributes significantly to the development of adequate public access along New Jersey’s shorefronts. (For more in depth description, please see Appendix A).

- Private Property Rights

As more and more people continue to move closer to tidal waterways and their shores, demand for these properties is surging. The right to own property is as important to citizens in this country as the right of public trust, and has a place in our basic founding principles. Thus, it is important to understand what rights private landowners have when their property is adjacent to tidal waterways and their shores.

- Riparian Rights

Riparian rights are the rights owners adjacent to tidelands have to be the first person to request to use those areas for purposes such as docking or mooring a boat. Because of the special nature of tidelands, owners must first get permission from the state to have land conveyed to them in the form of a tidelands license, lease or grant (see Section II B), and they must pay for this use. When the state does convey the private rights (jus privatum) to private ownership, the Public Trust Doctrine puts in place strict limitations on that conveyance. The governor’s signature is required to authorize the conveyance and it must be described clearly and definitively, with all ambiguities construed in favor of the state. Finally, the private owner in possession of the conveyance must not impair the public interest in the remaining lands and waters.

- Types of Conveyances

A tidelands grant is a deed from the state of New Jersey selling its tidelands. Tidelands grants are generally only issued for lands already filled in and no longer flowed by the tide. A tidelands license is a short-term revocable rental document to use tidelands, generally for structures such as docks, mooring piles and other temporary structures, in addition to dredging projects. Licenses have a specific term, usually three or five years. A tidelands lease is a long-term rental document to use tidelands, generally issued to marinas or homes over water. The term of a tidelands lease is generally 20 years. In some cases, the state of New Jersey agrees that it has no tidelands ownership interest in the owner’s property in a recordable document called a “Statement of No Interest.”

- Public Access

While the state may convey the private rights (jus privatum) associated with tidelands, it may never convey the public rights (jus publicum), and the private owner may never interfere with the public’s right to access tidal waterways and their shores adjacent to their property. While the private owner does have the right to use the conveyed property for the approved use, they must also be aware of the special nature of the lands and the public trust rights bestowed upon them.

- Conservation Restrictions

A private landowner may dedicate a portion of their property through a conservation restriction for a specific use. Conservation restrictions often take the form of easements. In this situation, the property owner maintains the right to use that parcel of land, but may not interfere with the agreed upon purpose described by the conservation restriction. For example, a property owner may be required to record a conservation restriction allowing public access across their property as a condition of developing the property. The parcel of land secured in the conservation restriction would become available to the public as an accessway to the shore. The public may not use that parcel for any other purpose than to reach the shore. The private landowner may use this parcel for any purpose, provided it does not interfere with the public’s ability to use it as an accessway. Conservation restrictions are recorded under the New Jersey Conservation Restriction and Historic Preservation Restriction Act (N.J.S.A. 13:8B-1 et. seq.).

- Liability Waivers

In recognition of the importance of the rights protected by the Public Trust Doctrine, New Jersey has enacted protections for landowners across and on whose lands public access is provided. Under the New Jersey Landowner Liability Act (N.J.S.A. 2A: 42A-2 et seq.) landowners who make their properties available for a variety of purposes are offered limited protection from the liability they would normally face under the common law. This includes the owners (or lessees/occupants) of premises upon which public access has been required as a condition of a regulatory approval of, or by agreement with, the Department of Environmental Protection; and the owners (or lessees/occupants) of premises on which a conservation restriction is held by the state, a local unit (for example, a municipality), a charitable conservancy, or premises upon which public access is allowed pursuant to a public pathway or trail easement held by one of these entities. This is an important protection for private landholders that can help to enhance coastal public access throughout the state.

Appendix A

State Implementation of Public Access – A More in Depth Look

- CAFRA (N.J.S.A. 13:19-21)

The Coastal Area Facility Review Act (N.J.S.A. 13:19-21) authorizes the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection to regulate and approve the location, design and construction of developments within a 1,376 square mile coastal region designated as the CAFRA area. This area encompasses portions

of Middlesex, Monmouth, Ocean, Burlington, Atlantic, Cape May, Cumberland and Salem Counties and includes coastal waters, barrier beach islands, coastal resort areas, portions of the Pinelands National Reserve and large agricultural areas. The act, enacted in 1973 and amended in 1993, was passed in an effort to thwart the “adverse economic, social and aesthetic effects” of unbridled development that was occurring in New Jersey’s coastal regions. By subjecting development activities to a state-issued permit process, the intention of the act is to ensure the best possible uses of land in the coastal area that “support diversity and are in the best long-term, social, economic, aesthetic and recreational interests of all people of the state.”

The law divides the CAFRA area into zones, and regulates different types of development in each zone. The CAFRA law regulates almost all development activities involved in public, residential, commercial, or industrial development, including construction, relocation, and enlargement of buildings or structures; and all related work, such as excavation, grading, shore protection structures, and site preparation, depending on the zone in which they are proposed.

- Waterfront Development Law (N.J.S.A. 12:5-3)

The Waterfront Development Law addresses new development proposed in and along tidal waterways. Anyone that proposes development in a tidally flowed waterway in New Jersey, including the construction of docks, piers, pilings, bulkheads, marinas, bridges, pipelines, cables, and dredging would need a Waterfront Development Permit. For development outside of the CAFRA area, the Waterfront Development Law regulates not only activities in tidal waters, but also the area adjacent to the water, extending from the mean high water line to the first paved public road, railroad or surveyable property line. The zone extends at least 100 feet but no more than 500 feet inland from the tidal water body. Within this zone, the Department of Environmental Protection must review construction, reconstruction, alteration, expansion or enlargement of structures, excavation and filling. However, this part of the law does not apply within the Hackensack Meadowlands Development District.

- Wetlands Act of 1970 (N.J.S.A. 13:9A)

The land immediately adjacent to tidal water often contains coastal wetlands. These wetland areas are a vital coastal resource serving as habitat for many creatures and as buffers that protect upland areas from the flooding, storm damage and pollution. The Wetlands Act of 1970 requires the Department of Environmental Protection to regulate development in mapped coastal wetlands, and to prevent their deterioration and destruction by regulating any activities including “dredging, filling, removing or otherwise altering or polluting, thereof”. The act led to the creation of an inventory and maps of tidal wetlands within the state. No regulated activity can take place on these lands without a permit and permit requests are granted, denied or limited based on consideration of public health and welfare, marine fisheries, shellfisheries, wildlife and the protection of property from flood, hurricane and other natural disasters.

- Riparian Lands Statutes

Tidelands Act (N.J.S.A. 12:3)

Tidelands, also known as "riparian lands," are lands now or formerly flowed by the tide of a natural waterway. This includes lands that were previously flowed by the tide but have been filled and are no longer flowed by the tide. These lands are owned by the state of New Jersey and held in trust for the public. Because of their special nature, tidelands are stringently managed and in some cases the state may enter into agreement with a private owner to convey to them use of the land. The rights of owners adjacent to tidelands to be the first

person to request to use those areas for purposes such as docking or mooring a boat are what are known as “riparian rights.” To use the land, the private owner must first get permission from the state in the form of a tidelands license, lease or grant, and then pay for this use. A tidelands grant is a deed from the state of New Jersey selling its tidelands. Tidelands grants are generally only issued for lands already filled in and no longer flowed by the tide. A tidelands license is a short-term revocable rental document to use tidelands, generally for structures such as docks, mooring piles and other temporary structures, in addition to dredging projects. Licenses have a specific term, usually three or five years. A tidelands lease is a long-term rental document to use tidelands, generally issued to marinas or homes over water. The term of a tidelands lease is generally 20 years. In some cases, the state of New Jersey agrees that it has no tidelands ownership interest in the owner’s

property in a recordable document called a “Statement of No Interest.” Whether a license, lease or grant is awarded is dependent on a variety of factors including the history of the property, the type of waterway the land is on, the proposed usage and the environmental conditions. Guiding this entire process are the Riparian Statutes compiled in Titles 12 and 13 of the New Jersey Statutes Annotated, with the most relevant provisions assigned to Chapter 3 (N.J.S.A. 12:3-1 et seq). Although the private rights (jus privatum) are conveyed in these situations, the public rights (jus privatum) are maintained.

- Coastal Zone Management Regulations (N.J.A.C. 7:7E)

In an effort to improve the Department of Environmental Protection’s coastal decision-making process, numerous coastal policies have been adopted as administrative rules, called the Coastal Zone Management Rules (CZM rules). These rules not only serve as the substantive core of the Department of Environmental Protection’s Coastal Management Program but they also ensure the enforceability of the coastal laws, including the four described above. The department amends these rules from time to time. By serving as the guiding principle of the state’s coastal laws and as the basis for all state coastal permit decisions, the CZM rules help to add clarity to coastal decisions made in New Jersey. These rules are divided into three categories:

- Location rules consider the characteristics of a special location within the coastal zone, such as wetlands;

- Rules are used to analyze appropriate uses within the coastal zone, such as housing or marinas; and

- Resource rules focus on controlling the effects of development within the coastal zone, such as maintaining public access to the waterfront.

Therefore, depending upon the proposed use, project design, location, and surrounding region, different rules in each of the three steps are applicable in the coastal decision-making process. The two primary rules that focus on public access are described below.

- Public access to the waterfront rule (N.J.A.C. 7:7E-8.11)

Within the resource rules, a section is dedicated to public access to the waterfront (N.J.A.C. 7:7E-8.11), where public access is clearly defined and strict standards are issued to help guide development in the coastal zone to include public access. Here, public access to the waterfront is defined as “… the ability of all members of the community at large to pass physically and visually to, from and along the ocean shore and other waterfronts.” (N.J.A.C. 7:7E-8.11a). Further, the rule goes on to say that “Coastal development adjacent to all coastal waters, including both natural and developed waterfront areas, shall provide permanent perpendicular and linear access to the waterfront to the maximum extent practicable, including both visual and physical access. Development that limits public access and the diversity of the waterfront experiences is discouraged.” (N.J.A.C. 7:7E-8.11b). According to this rule, each shorefront development proposal must address standards related to access including reasonable fees for access, providing adequate parking and facilities, and clearly marking public access locations.

- Hudson River waterfront area rule (N.J.A.C. 7:7E-3.48)

Also within the CZM rules is a rule specific to the Hudson River Waterfront Area, which encompasses a 17.4-mile long expanse along the Hudson River between the George Washington Bridge in Bergen County and the Bayonne Bridge in Hudson County. The Hudson River Waterfront Area rule (N.J.A.C. 7:7E-3.48) sets forth development standards for public access and open space along the Hudson River Waterfront Area, and requires development, maintenance, and management of a section of the Hudson Waterfront Walkway coexisting with the shoreline of the development property. The Hudson River Waterfront Area Rule requires all owners of property within this area who desire a NJDEP waterfront development permit to comply with the following:

- construct and maintain a sixteen-foot wide walkway along the entire waterfront of the property, to be built to standards specified in NJDEP regulations;

- convey to NJDEP a conservation restriction for the walkway

- allow perpendicular public access to the walkway.

- Statute – N.J.S.A. 40:61-22.20 - Municipal control over beaches, etc.; fees

In 1955, a statute was enacted that authorized New Jersey municipalities bordering the Atlantic Ocean, tidal water bays or rivers to charge a fee to beachgoers in order to account for maintenance and safety costs associated with them. N.J.S.A.40:61-22.20 grants municipalities “exclusive control, government and care thereof” of any municipally-owned lands on the Atlantic Ocean, tidal water bays or rivers and of boardwalks, bathing and recreational facilities, safeguards and equipment. The fees charged for access to the beach

and bathing and recreational grounds must be reasonable, shall not be charged for children under the age of 12 years and may be reduced or eliminated for those over 65 or those who are disabled. Fees collected can only be used to improve, maintain and police the property, to provide protection from erosion and other sea damage and to provide facilities and safeguards for public bathing and recreation.

- State Capital Spending Programs

New Jersey’s capital spending programs include the department’s land acquisition program Green Acres and its Shore Protection program within the department’s Office of Engineering and Construction. Because federal, state and municipal funds are used to support the projects of each of these programs, requirements of public access are built into their agreements and significantly contribute to the development of adequate public access along New Jersey’s shorefronts.

- Green Acres

The Green Acres Program, created in 1961 to meet New Jersey's growing recreation and conservation needs, determines how funds may be spent for park and open space acquisition. The Green Acres program uses a stable source of funding provided by the Garden State Preservation Trust Act. These funds are available to county and municipal governments as well as nonprofit organizations. Green Acres funds have been used to acquire numerous waterfront sites for public use, enabling public access along the shoreline throughout New Jersey. These sites include Seven Presidents Park in Monmouth County, Liberty State Park in Hudson County and various smaller parks along the state’s ocean, bay and river shorelines. As a condition of applying for and receiving Green Acres funding, municipal recipients of the funding are required to prepare a Recreation and Open Space Inventory (ROSI) of lands they hold for recreation and conservation purposes. The property funded is included on the ROSI and subject to Green Acres restrictions, including public access requirements. By preserving open space, maintaining a database of each of the ROSIs, and requiring that funded property is open to the public, Green Acres is an integral program that helps to provide public access to the coast.

- Shore Protection

New Jersey's Shore Protection Program was created through state legislation, to provide for the protection of life and property along the coast, preserve the vital coastal resources of New Jersey, and maintain safe and navigable waterways throughout the state. The Shore Protection program is administered through the department’s Office of Engineering and Construction. Among other responsibilities, the office is responsible for administering beach nourishment, shore protection and coastal dredging projects throughout the state. Of particular importance to public access are the beach nourishment and shore protection projects.

- Shore Protection and Beach Nourishment Projects

The Office of Engineering and Construction, often in cooperation with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, provides beach nourishment and re-nourishment projects for the purpose of restoring New Jersey's beaches and also installs and maintains shore protection structures. Numerous beachfront communities, from Sandy Hook to Cape May, have worked together with the Office of Engineering and Construction to take advantage of the protective measures beach nourishment provides. Depending on the purpose and location of the project, funding may be available from several sources. For federal projects, the federal government contributes 65 percent of the project cost while the remaining 35 percent is divided into a cost-share between the state and the local governments. Non-federal projects are funded through a state/local cost-share, with the state contributing 75 percent and the local governments contributing 25 percent. Design and real estate acquisition costs are the responsibility of the local sponsor.

- Public Access

In addition to the historic legal rights retained by the public to tidal areas, substantial funds are invested in shore protection. For these reasons, the expenditure of state monies for beach nourishment and shore protection structures carries with it a requirement for public access to these areas, including parking and restrooms. Municipal and county governments must demonstrate that adequate public access, clearly defined in the aid agreements signed with the state, will be provided.

|