The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted that proactive monitoring of circulating pathogens is important. Wastewater surveillance gained traction in the United States during the pandemic and has become an efficient way to survey community health throughout the country. This type of testing offers unbiased insight into circulating, population-level disease trends and can allow for targeted health decisions. The results from wastewater surveillance are not reliant on people getting tested on their own and additionally, protects people’s privacy, as results cannot be traced back to individuals.

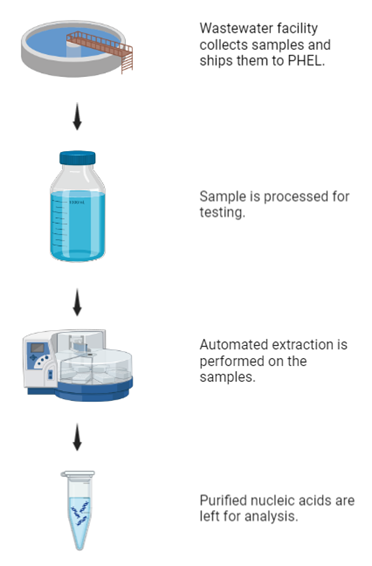

When a person gets sick, with either bacteria or viruses, they can often shed the virus in their feces/stool when they use the bathroom. After flushing the toilet, the virus travels through the sewage system and eventually ends up at a wastewater treatment facility (if their home is connected to a municipal sewer system). The wastewater technicians take a sample of wastewater, before it is treated, and send it to the laboratory. At the laboratory, scientists test the wastewater sample for pathogens and report the data to the Center for Disease Control’s COVID Data Tracker for Wastewater Surveillance. Public health officials can use this data to influence public health decisions within communities such as, increasing mobile testing and vaccination sites. Originally, wastewater testing was used primarily for COVID-19 detection. However as testing capabilities expand, more pathogens can be monitored to better serve communities.

The Wastewater Unit of the Public Health and Environmental Laboratories (PHEL) provides testing for pathogens in wastewater. The Wastewater Unit works closely with the New Jersey Department of Health Communicable Disease Service (CDS), the National Wastewater Surveillance System (NWSS), as well as a variety of wastewater treatment facilities that are actively participating in the program. These treatment plants service thousands of individuals. This provides data for a large proportion of the state of New Jersey population, but additionally, ensures individual and household anonymity. These treatment plants send samples to the New Jersey PHEL twice a week to be tested.