|

Protection Through RestorationBy: Rob Schrader The Delaware Bay & River The Delaware Bay and River receives 70% of all the crude oil entering the ports on the eastern seaboard of the United States.1 Approximately 1.25 billion barrels of oil is imported on approximately 1,000 vessels that stop at the Ports of Philadelphia and Wilmington. The Delaware Bay and River is an important wetlands and wildlife habitat. This sensitive area provides a safe harbor for the nesting waterfowl, migrating waterfowl, non-game species such as the Osprey (Pandion haliaetus) and American Bald Eagle (Haliaeetus leucocephalus), and wintering waterfowl. In addition to the waterfowl, the bay supports a million or more shorebirds in late spring as over 20 species migrate between Southern Hemisphere wintering grounds and arctic breeding grounds. The abundant food resources of the Delaware Bay, principally the eggs of the horseshoe crab, allow shorebirds to store sufficient energy to complete their migration. Because most of the world population of certain species is concentrated along the shores of the Delaware Bay at one time, oil spills have the potential to cause catastrophic damage. Even spills that affect only the food sources could result in a subsequent death of the shorebirds requiring years for the populations to recover. Along with the threat to shorebirds, other sensitive resources are affected in and around this estuary, including shellfish, sport, and commercial fisheries, diving waterfowl, and resident birds. In addition, this area also provides a prime location for recreation and eco-tourism for the public. Protection Strategies In the summer of 1990, the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection, Bureau of Emergency Response (BER) along with the Delaware Bay River Cooperative (DBRC) surveyed approximately 75 miles of the New Jersey Shoreline from Cape May to the Delaware Memorial Bridge. This survey was to plan strategic protection strategies at each Gut, Creek, washout and tributary that feeds the River. The final strategies were based on the following hierarchy of controls: 1) physical processes in the creek, gut or tributary; 2) protection priorities; and 3) probable effectiveness of response. Because the basic assumption was that the strategy be designed to deal with spilled oil to the creeks from the open bay, the protection strategies that were proposed emphasized flood-tidal conditions. These proposed strategies were based on the information at hand on wave action, tidal currents and based on normal weather patterns for the area. The majority of the areas have no vehicular access. The shoreline is a high-energy shoreline that consists of root substrate, mud and the indigenous grasses of the area. Of the 71 estuaries, 67 of them will need permanent anchor points because setting traditional anchors would cause more environmental damage and would in most cases not be strong enough to hold the proposed boom. In addition, the permanent anchor points would greatly reduce boom deployment time, thus averting catastrophic damage to the wetlands making the pilings the preferred method for the many areas. However, funding for such pilings would have to be found. All these strategies are now Annexed to the USCG Port of Philadelphia Area Contingency Plan.2 The Spill In October of 1996, while enroute to New York from Texas, the barge Bouchard B155 carrying 150,000 barrels of #6 fuel oil entered the Delaware Bay to weather out a Nor’easter that was affecting the regional area. The B155 anchored in the Bombay Hook anchorage 8.5 nautical miles from Nantuxent Cove. The crew of the barge had been aware of oil in the anchor compartment before anchoring. On October 24, 1996, the NJDEP Bureau of Emergency Response was notified that oil had been discovered on the shoreline at the small coastal village of Point Bay, Cumberland County.3 The responsible party (RP) had accepted responsibility and hired a clean up crew. The oil had formed “tar balls” and fouled the entire length of the village. These tar balls were mixed in with the rack line and consisted of vegetative debris. The rack line was 4-5 meters wide and the coverage of oil was patchy 20-30% to sporadic 5-10%.4 Studying the trajectory of the oil movement, it was probable that oil had also affected an area just north of Point Bay.

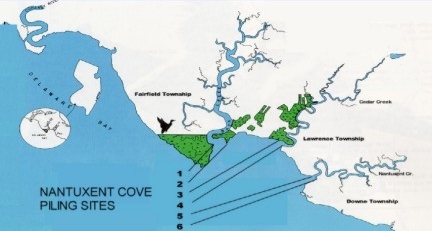

A survey of the 3.5 nautical mile area from Nantuxent Creek to Ben Davis Point revealed that the oil had sporadically affected the entire length of shoreline from waters edge to approximately 30 meters into the marsh. Oil coverage was patchy, with approximately 10% of the marsh area affected. Within these patches, oil covered the upper half of the marsh vegetation. A visible sheen was observed emitting from the oil globules on the substrate and running into the water (see Figure 1). A decision not to clean the wetlands and not cut the grass was based in part due to findings of a NOAA study on a spill on the upper Delaware River, July 1992. In that finding, NOAA scientist Edward Livine found that vegetation that is light to moderately fouled with or with out cutting resulted in no long-term negative impact. Flowering and seed production by most of the vegetation in the affected areas had also indicated that plants were not stressed by the oil or by cutting any of the methods.5 Natural Resource Damage Assessment According to 43 CFR 11.14, in most spills, a State trustee shall act on behalf of the public as trustee for natural resources, including their supporting ecosystems, within the boundary of a state or belonging to, managed by, controlled by, or appertaining to such state.6 In the event of an oil spill, in the State of New Jersey, the state trustee, in conjunction with the federal government trustees, work with the parties responsible for the spill to restore any resulting injury to the public’s resources. In most cases, before restoration* can occur, the governments must first assess the type and extent of the natural resources injury. Depending upon the specifics of the spill, (oil type, weather, affected resources, etc.) and the level of cooperation from the responsible party, the assessment process and succeeding natural resources restoration may take a considerable amount of time and money. In order to speed the restoration of the public’s natural resources and keep assessment cost at a minimum, New Jersey’s Office of Natural Resource Damage (ONRD) has adopted a policy of forgoing the assessment phase of natural resource restoration in the event of very small spills with limited or ephemeral natural resource injury. The decision to immediately pursue restoration without assessment is made only after the responsible party has agreed to a specific restoration project and the cost of assessing injury will likely be greater that the cost of the injury itself (or restoration thereof).7 The oil from the October 1996 barge spill that came ashore in the Nantuxent Cove area of New Jersey was of relatively low toxicity and limited extent, and deposited on vegetation that had already begun its seasonal senescence. Therefore, ONRD, NOAA, and the responsible party agreed that the spill resulted in minor injury to the salt marsh and that a small restoration project in the area of the spill would be an appropriate measure to compensate the public for the injury. Several restoration options were considered, but based on a suggestion by the author, ONRD and NOAA determined that construction of permanent boom anchors at the mouth of the three creeks emptying into Nantuxent Cove was the best option. The presence of the boom anchors would allow for rapid deployment of protective booms in the event of future oil spills, a level of protection that does not currently exist in these ecologically sensitive areas.

The project was to be enhanced by the placement of osprey (a threatened species) nest platforms in five of the six boom anchor pilings. These pilings would have to be placed at the mean high water mark and would have to be a single pole structure with a platform on the top 14-16’ high. The nesting box would include a perch equal or greater in height to the nest on either side. The Project Because this was a new concept in protecting the wetlands, the NJDEP’s ONRD drafted a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) where ONRD oversees the settlement and makes monies available to BER for projects such as the installation of the booming anchor poles. The project needed both state and Army Corps of Engineers permits for the installation. The permitting process was both tedious and frustrating. Three of the six poles were to be located on State Property; three were to be located on private property. Permission was needed from the property owners as well as from the three municipalities Planning Boards and the Cumberland County Freeholders. All were highly enthusiastic for the project. The US Army Corps of Engineers was asked to participate. They had a shallow draft construction barge with a 130’ crane, which was perfect for the Project. The US Army Corps of Engineers entered a MOU with the NJDEP to install the pilings. Public Service Electric & Gas, a utility in the State and operators of the Salem Nuclear Power Plant, were asked if they would donate six 35’ poles for the project. Public Service Electric & Gas, Environmental Director had no hesitations, six poles were slated for the project and were delivered to the Fort Mifflin Army Corps of Engineers yard in Philadelphia. The nests were built by Citizens United, a non-profit organization that routinely builds, installs and tends osprey nests on the Maurice River. The Cumberland County Road Department under the direction of the Office of Emergency Management delivered these nests. Installation The week of September 22, 1998 was selected for installation. This week was selected because tides were favorable; having a high tide in mid afternoon. The Barge Titan began the installation process. With small river tugs, the barge and crane were pushed to the pre-designated position on the north side of the Nantuxent Creek. There they dropped the barge stabilizers and set the pilings. Once the pole was driven to a depth of approximately 20 feet, the nesting box was installed on the top. Approximately 1.5 metes from the bottom, a 12-inch eyebolt was through bolted for the boom anchor. That afternoon the southern pole was set and the nest was placed. The project was completed in four days, one day over budget due to small logistical problems. In all the installation of the Osprey nests/anchor points went very well. The Test Since the original survey in 1990, DBRC has been testing and proving all of the strategies for the Delaware River. In only two incidents, was DBRC activated to boom off any NJ creeks in the lower Delaware Bay. In response to the NJDEP installing the anchoring points, DBRC pledged that they would test the pilings in Back Creek, the northern most creeks in Nantuxent Cove. On October 19, 1998, DBRC arrived at Cedar Creek at 8 am with a small barge loaded with 3,000 feet of boom, 3 small boats and 10 men. Tides that day were favorable, low tide being at 0810 and high tide at 1315. Currents were averaging 1.2 knots.

Conclusion This unique pilot project will drastically shorten the response time to place protective booms in remote locations. In most cases, an oil spill in the Delaware Bay does not go unnoticed. Lead-time and trajectories for where the oil will impact are made by NOAA to the Coast Guard. The RP will direct DBRC or a contractor to boom the area. Although, boom placement has been pre-designated in the Area Contingency Plan, the contractor if not familiar with the area can only guess where the boom is to be placed to be effective. In most cases, the response time to the area would be 2-3 hours and then possibly 5 hours to boom any one of the creeks. With the nesting poles/booming anchors in place, the 6-8 hour response time to these remote areas will be cut in half. With the pre-designated anchor points, there is no question where the boom will be placed and with the rapid response, damage to the wetlands is reduced; thus, damage assessment and clean up costs are reduced. The booming anchor/osprey habitat concept is good for both the environment and for the shipping industry. The Bureau of Emergency Response has been a working partner with DFG&W/ONRD on numerous spills since the October 1996 incident on the Delaware River. This partnership has provided the State of New Jersey numerous projects on many of our creeks and rivers. At this time, settlements from spills in the Pennsauken Creek and the Woodbridge Creek have provided monies for the protection of these valuable estuaries as projects pending. The New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection has taken a step in the protection of the Delaware Estuary and to the wetlands along our shoreline. The concept of Protection through Restoration is new. The success of this pilot program and the overall acceptance by industry, ONRD, NOAA, DFG&W, and The U.S. Department of Interior, has enabled this concept to blossom to national notoriety and will continue to provide protection to our riverine and coastal environment for years to come setting nesting poles/booming anchors where needed.

|

| To report an environmental

incident impacting NJ, call the Toll-Free 24-Hour Hotline |

||

Contact DEP | Privacy Notice | Legal Statement & Disclaimers | Accessibility Statement |

||

Site Remediation Program: SRP

Home | About SRP |

Search | Help Copyright © State of New Jersey, 1996- |