Delaware • New Jersey • Pennsylvania

New York • United States of America

- Aquatic Life Designated Use Project

- Bacteria Monitoring

- Biomonitoring Program

- Chlorides Monitoring

- Contaminants of Emerging Concern

- Delaware Estuary Water Quality Monitoring Program

- Dissolved Oxygen and Nutrients

- Modeling

- Other Monitoring (e.g., Toxicity, Fish Tissue, Metals)

- PCBs and PMPs

- Special Protection Waters (SPW)

- Water Resource Data Sets

Indigenous Populations

Native Americans lived in the Delaware River Valley long before its "discovery" by European explorers.

European Settlement

In 1609, Henry Hudson first sailed into the Delaware Bay, and the region began to be colonized a few decades later.

The river basin was a major part of the American Revolution and played a key role in defining and shaping the fledgling nation.

By the early eighteenth century, pollution began to be a recognized problem.

Industrial Revolution to World War II

Rapid population growth, increased industrial activities and the limited treatment of these waste streams caused even more pollution in the Delaware River, particularly in the tidal reaches of its urban centers (Philadelphia, Camden and Wilmington).

Severe pollution was most evident by the prevalence of waterborne illnesses and in the sharp decline of migratory fish populations, such as the American shad.

|

|

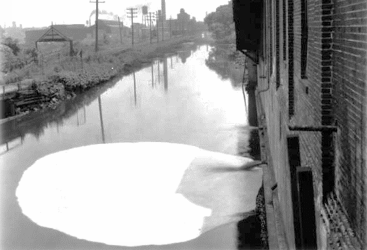

| Slaughterhouse waste discharge in Philadelphia, Pa., 1928. Photo courtesy of the Philadelphia Water Department Historical Collection. | A fishkill in Philadelphia, Pa., circa 1929. Photo courtesy of Temple University Archives. |

By the height of World War II, the tidal Delaware River was largely considered an open sewer for public and industrial waste, and pollution was rampant. The river's water was so foul that it would turn the paint of ships brown as they traveled through or were docked for any period of time. People were sickened by simply the smell of the river.

Additionally, there were parts of the estuary that were considered dead zones, void of aquatic life, because of limited or no dissolved oxygen (DO). These zones of "anoxia" (a lack of DO) or "hypoxia" (severe depression of DO) inhibited the survival of fish and other aquatic life that need oxygen in the water to breathe. It also prevented migratory fishes, such as American shad, from completing their runs to the upstream spawning grounds and the return migration of juvenile fish back to the sea.

By the mid-1900s, the pollution in the Philadelphia section of the Delaware Estuary was so severe that in the summer and early fall (May-November), there was essentially no DO in the Delaware River on a typical day.

This water pollution problem was a key factor in the formation of the DRBC in 1961 and in federal and state water pollution control laws of the 1960s and 1970s.

DRBC Formed in 1961

After the DRBC was created in 1961, it went right to work to address Delaware Estuary water pollution.

The Commission's first Water Quality Regulations were adopted in March 1967. They are divided into two main sections: Article 3 - Water Quality Standards for the Delaware River Basin and Article 4 - Application of Standards.

To address an important oxygen-consuming pollutant known as CBOD (carbonaceous biochemical oxygen demand), a waste load allocation was developed in 1968, which factored in the waste assimilative capacity of the tidal Delaware River (the predecessor to today's "Total Maximum Daily Loads").

The Federal Water Pollution Control Act Amendments of 1972, commonly referred to as the Clean Water Act, further assisted the implementation of water pollution control efforts in the basin, as did state-led efforts.

By the late 1980s, over one billion dollars had been spent on improving municipal wastewater treatment facilities in the Delaware River Basin, which benefited human communities along the river and strengthened fish populations.

How About Now?

As a result of these efforts, the DO levels in the Delaware Estuary steadily improved, to the point where oxygen levels now meet water quality criteria (e.g., 3.5 mg/L average DO concentration around Philadelphia's Ben Franklin Bridge). Fish populations in this region of the estuary, as well as migratory fish, have returned.

The amazing DO restoration seen in the Delaware Estuary - from essentially no oxygen for 6 months each year to achieving levels such as the 3.5 mg/L standard - is hailed as one of the world's top water quality success stories.

DRBC has been monitoring DO in the Delaware Estuary for over 50 years. While there continues to be a summertime DO sag in the most urbanized part of the estuary, DO levels have greatly improved since the 1960s.

- View Water Quality Data, including current dissolved oxygen levels in the Delaware River Estuary

- Graphic of how DO levels in the Delaware River at the Ben Franklin Bridge have Improved since 1965 (jpg)

- Graphic of July & August Dissolved Oxygen Levels at the Ben Franklin Bridge (Philadelphia, Pa.) 1964-2024 (jpg)

Check out this animated graphic showing summertime (July and August) DO improvement from the late 1960's through 2024.

Please note: In the graphic, the criteria line is 24-hour mean DO, while the measurements are daytime spot measurements near surface.

Created by: John Yagecic, P.E., DRBC Water Quality Assessment Manager

DRBC's Current Efforts to Further Improve DO

- DRBC Map: DRBC Water Quality Zones for the Main Stem River (pdf)

- DRBC Presentation: Continuing Restoration of DO in the Delaware Estuary - Historical Data and Current Efforts (pdf; 2010)

- Article: Estuarine oxygen dynamics: What can we learn about hypoxia from long-time records in the Delaware Estuary (pdf; U. Del.'s Jonathan Sharp, Limnol. Oceanogr., 55(2), 2010, 535-548)

- Article: The Delaware River Revival: Four Centuries of Historic Water Quality Change from Henry Hudson to Benjamin Franklin to JFK (pdf; 2010 by Gerald J. Kauffman, Jr.)

- Article: The Historical Context of Water Quality Management for the Delaware Estuary (pdf; 1988 by Richard C. Albert)

Copyright © Delaware River Basin Commission,

P.O. Box 7360, West Trenton, NJ 08628-0360

Phone (609)883-9500; Fax (609)883-9522

Thanks to NJ for hosting the DRBC website